I always write to music, but a problem arose recently that made me question my writing ritual.

I always write to music, but a problem arose recently that made me question my writing ritual.

But I love writing with my headphones on, music blocking out the world around me. There’s no better way for me to strike the right mood in the WIP. I create a playlist for each book, with overlapping “series songs.” Songs I listen to only while writing books in that series. Since my series are vastly different so are the songs in each playlist.

As soon as I slide on the headphones, the music transports me back to my story world.

The problem I ran into recently was with writing true crime. I’d created a playlist for Pretty Evil New England. But for this new book I veered away from my usual writing routine and threw on Pandora.

Big mistake.

I struggled. The words wouldn’t come like they normally do. My mind felt cluttered and bogged down. Hence why I wrote my last post about multitasking and the brain. Frazzled, I panicked. Why I couldn’t reach “the zone” with my WIP? The beginning had been so easy, words flowing like Niagara, paragraphs in perfect harmony with one another. Had I finally lost my writing mojo?

The answer seemed clear. Only it wasn’t an answer I could accept. I emotionally degraded myself, exercised, read . . . I tried everything I could think of to breathe life into my muse, dying next to two unfinished WIPs. And yet, every time I slid on the headphones and clicked Pandora . . . total brain block.

After several grueling days (felt more like years), I stumbled across a blog post that advised writers never to listen to music unless it has no lyrics, background instrumental music. In other words, the total opposite of my music. But I’ve written all my books to music. What changed?

The metaphoric lightbulb blazed on.

By switching to Pandora, not knowing what song would play or when, my brain couldn’t interpret the music as white noise.

By switching to Pandora, not knowing what song would play or when, my brain couldn’t interpret the music as white noise.

As soon as I went back to YouTube and clicked the playlist for Pretty Evil New England (since I’m writing true crime), my fingers could barely keep up with the flood of creativity.

I’m back!

Writers have writing rituals/routines for a reason. The ritual or routine encourages focus and has the ability to get us back on track if we drift off course. The familiarity snaps us out of the funk and reminds us that yes, we can finish the WIP, just as we’ve always done. It also allows the words to flow. Rituals help us find comfort and balance and sets the tone for a solid writing session. Routine is especially important. Employing a consistent writing routine can be the difference between hitting our word count or staring at a blinking cursor.

If your writing comes to a screeching halt for no apparent reason, a change within your writing ritual or routine may be to blame.

For me (obviously), it’s sliding on the headphones with a familiar playlist cranked. Emphasis on familiar. An argument could be made that I’m not really listening to music. Rather, the playlist morphs into white noise and acts as the gunshot to start the footrace. Although, strangely, I’ve tried the white noise app and it’s not nearly as effective (for me). All my research is done on my iMac, but I switch to my MacBook to write. This was a subconscious act. I wasn’t even aware of the ritual until I focused on changes within my writing routine.

For others, the writing ritual may include an environmental change, like shutting the door to the office or sitting outside in a special chair. Some writers trek to the local coffee shop or settle in at their designated desk in the university library. *waves to Garry*

Some of our most celebrated authors had/have consistent writing rituals and routines.

JAMES JOYCE

Joyce’s ritual included crayons, a white coat, and a comfy horizontal surface. For word flow, he would lay flat on his stomach in bed. Since he was severely myopic, crayons enabled Joyce to see his own handwriting more clearly, and the white coat served as a reflector of light.

MAYA ANGELOU

In her own words:

I keep a hotel room in my hometown and pay for it by the month.

I go around 6:30 in the morning. I have a bedroom, with a bed, a table, and a bath. I have Roget’s Thesaurus, a dictionary, and the Bible. Usually a deck of cards and some crossword puzzles. Something to occupy my little mind.

I think my grandmother taught me that. She didn’t mean to, but she used to talk about her “little mind.”

So when I was young, from the time I was about 3 until 13, I decided that there was a Big Mind and a Little Mind. And the Big Mind would allow you to consider deep thoughts, but the Little Mind would occupy you, so you could not be distracted. It would work crossword puzzles or play Solitaire, while the Big Mind would delve deep into the subjects I wanted to write about.

I have all the paintings and any decoration taken out of the room. I ask the management and housekeeping not to enter the room, just in case I’ve thrown a piece of paper on the floor, I don’t want it discarded. About every two months I get a note slipped under the door: “Dear Ms. Angelou, please let us change the linen. We think it may be moldy!

But I’ve never slept there, I’m usually out of there by 2. And then I go home and I read what I’ve written that morning, and I try to edit then. Clean it up.

TRUMAN CAPOTE

The creative genius behind In Cold Blood was a superstitious man. Capote’s writing ritual often involved avoiding things like hotel rooms with phone numbers that included the number 13, starting or ending a piece of work on a Friday, and tossing more than three cigarette butts in one ashtray.

I am a completely horizontal author. I can’t think unless I’m lying down, either in bed or stretched on a couch and with a cigarette and coffee handy. I’ve got to be puffing and sipping. As the afternoon wears on, I shift from coffee to mint tea to sherry to martinis.

No, I don’t use a typewriter. Not in the beginning. I write my first version in longhand (pencil). Then I do a complete revision, also in longhand. Essentially I think of myself as a stylist, and stylists can become notoriously obsessed with the placing of a comma, the weight of a semicolon. Obsessions of this sort, and the time I take over them, irritate me beyond endurance.

Even so, Capote stuck to his writing routine because it worked.

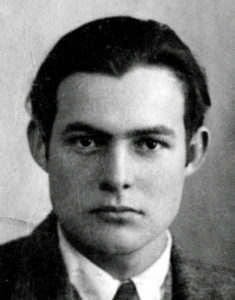

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

In stark contrast to James Joyce, Hemingway was a firm believer in standing while writing. While working on The Old Man and The Sea, he followed a strict regimen.

“Done by noon, drunk by three.”

This entailed waking at dawn, writing furiously while standing, and eventually hiking to the local bar to get hammered.

JOAN DIDION

Didion holds her books close to her heart—literally. When she’s close to finishing a manuscript, she’ll sleep with her WIP.

“Somehow the book doesn’t leave you when you’re asleep right next to it.”

E.B. WHITE

In his own words:

I’m able to work fairly well among ordinary distractions. My house has a living room that is at the core of everything that goes on: it is a passageway to the cellar, to the kitchen, to the closet where the phone lives. There’s a lot of traffic. But it’s a bright, cheerful room, and I often use it as a room to write in, despite the carnival that is going on all around me.

KURT VONNEGUT

Check out Vonnegut’s writing routine:

I awake at 5:30, work until 8:00, eat breakfast at home, work until 10:00, walk a few blocks into town, do errands, go to the nearby municipal swimming pool, which I have all to myself, and swim for half an hour, return home at 11:45, read the mail, eat lunch at noon. In the afternoon I do schoolwork, either teach or prepare.

When I get home from school at about 5:30, I numb my twanging intellect with several belts of Scotch and water ($5.00/fifth at the State Liquor store, the only liquor store in town. There are loads of bars, though.), cook supper, read and listen to jazz (lots of good music on the radio here), slip off to sleep at ten. I do pushups and sit ups all the time, and feel as though I am getting lean and sinewy, but maybe not.

JODIE PICOULT

Picoult doesn’t believe writer’s block exists:

Think about it — when you were blocked in college and had to write a paper, didn’t it always manage to fix itself the night before the paper was due? Writer’s block is having too much time on your hands. If you have a limited amount of time to write, you just sit down and do it. You might not write well every day, but you can always edit a bad page. You can’t edit a blank page.

Wise words. I agree. Nothing motivates quite like a looming deadline, self-imposed or contracted.

DAN BROWN

Most writers would do anything and everything to get rid of writer’s block. According to The Da Vinci Code novelist, Dan Brown hangs upside down to cure writer’s block. Sounds crazy, doesn’t it? But we can’t argue with the results. If Brown didn’t hang like a bat, imagine all the amazing thrillers we would have lost?

Bats can’t launch into flight until they’re upside down. Why not Dan Brown? He says he’s more productive and creative afterward. He also does push-ups and stretches every hour. Not only has he found the cure for writer’s block, he’s in tip-top shape.

Writers are complicated beings. 😉

Do you have a writing ritual and/or routine? Tell us about it.

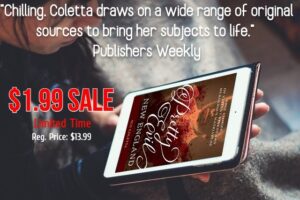

My publisher ran a sale for Pretty Evil New England last week. Not sure how long the sale will last, but for now the ebook is $1.99 on Amazon.

If I may indulge in a little horn toot today. My latest release has dropped—just don’t drop it on your foot. Because the print version comes in at a honkin’ 612 pages (173k words). It looks nice on a shelf but will also work as an emergency doorstop. It sells for $28.95.

If I may indulge in a little horn toot today. My latest release has dropped—just don’t drop it on your foot. Because the print version comes in at a honkin’ 612 pages (173k words). It looks nice on a shelf but will also work as an emergency doorstop. It sells for $28.95.

Sometimes it’s just plain hard to write. Like when you’re sick. Or feeling drained from a job. I recently went through a season of this, a mix of some medical stuff and general lethargy. For the first time in 25 years, I found myself missing my weekly quota disturbingly often.

Sometimes it’s just plain hard to write. Like when you’re sick. Or feeling drained from a job. I recently went through a season of this, a mix of some medical stuff and general lethargy. For the first time in 25 years, I found myself missing my weekly quota disturbingly often. One of the more ubiquitous quotes about writing out there, almost always attributed to Hemingway, is: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

One of the more ubiquitous quotes about writing out there, almost always attributed to Hemingway, is: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” I always write to music, but a problem arose recently that made me question my writing ritual.

I always write to music, but a problem arose recently that made me question my writing ritual. By switching to Pandora, not knowing what song would play or when, my brain couldn’t interpret the music as white noise.

By switching to Pandora, not knowing what song would play or when, my brain couldn’t interpret the music as white noise.

Here at TKZ we love to talk about the nuances of the craft. These take the form of both things to do and things not to do. As Brother Gilstrap likes to remind us, these aren’t “rules.” They are, however, basics that work every time, and if you choose to ignore them, that’s your business. But if your business is also to make dough with your writing—which means connecting with a large slice of the reading public—you would be wise to attend to the fundamentals.

Here at TKZ we love to talk about the nuances of the craft. These take the form of both things to do and things not to do. As Brother Gilstrap likes to remind us, these aren’t “rules.” They are, however, basics that work every time, and if you choose to ignore them, that’s your business. But if your business is also to make dough with your writing—which means connecting with a large slice of the reading public—you would be wise to attend to the fundamentals.