by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

We’ve had some robust discussions over the years on this matter of “rules” for writers. That word always seems to raise hackles (hackles, n., the erectile hairs along the back of a dog or other animal that rise when it is angry or alarmed).

We’ve had some robust discussions over the years on this matter of “rules” for writers. That word always seems to raise hackles (hackles, n., the erectile hairs along the back of a dog or other animal that rise when it is angry or alarmed).

There are two standard rejoinders when someone mentions “rules” for writing fiction.

First, somebody will inevitably quote Somerset Maugham’s dictum: “There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.” (There, I did it for you.)

The second reaction is more direct: “There are no rules!” (Always with the exclamation point.)

Now, while I don’t recoil at the word rules, my preferred nomenclature is fundamentals. What makes something a fundamental? It works. Fundamentals keep the writer—especially the novice—from obvious errors that frustrate the basic relationship between writer and reader.

“Your mother was a hamster…”

But slip in the word rules and a chorus will rise, with variations on the theme: “Shackle us no shackles! A pox on your rules! And your mother was a hamster and your father smelt of elderberries!”

I believe the root of this objection is really a tacit recognition that rules have exceptions. But you’ve got to know a rule before you understand the alternatives. You’ve got to learn the scales before you start playing jazz. You’ve got to master the two-handed chest pass before you start with the no-look, behind-the-back dish. (“Pistol” Pete Maravich and Earvin “Magic” Johnson practiced the fundamentals for countless hours before they became magicians on the court.)

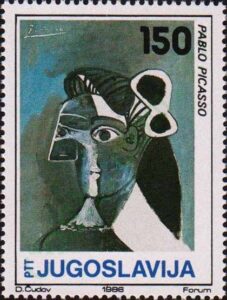

As Alice K. Turner, for many years the fiction editor at Playboy, put it: “If you’re good enough, like Picasso, you can put noses and breasts wherever you like. But first you have to know where they belong.”

The above was throat clearing. Now on to today’s post!

CATO and Its Exceptions

Let’s discuss the character alone, thinking, opening (CATO).

You want readers to connect to your story from the jump, right? I mean, what’s the alternative?

Long experience tells me that the fastest way readers are pulled into a story is when they see a character in motion responding to a disturbance. This is a fundamental for a simple reason: it works every time.

The CATO, on the other hand, is too often slow and uninvolving. The writer thinks that jumping immediately into the inner sanctum of a character’s mind will create for the reader the same emotional bond the writer has with the character. But that’s because the writer has lived and breathed with that character, and knows how the character acts and reacts. Readers don’t know those things yet. They need to see action before they care about thoughts.

That’s why writers are well advised, as a general rule guideline, to avoid the CATO.

Unless…they know how to bring something more to it.

In a TKZ Words of Wisdom we revisited a post by our own Kris (P. J. Parrish) on the subject of openings. This quote struck me:

But I’m tired of hooks. I’m thinking that the importance of a great opening goes beyond its ability to keep the reader just turning the pages. A great opening is a book’s soul in miniature. Within those first few paragraphs — sometimes buried, sometimes artfully disguised, sometimes signposted — are all the seeds of theme, style and most powerfully, the very voice of the writer herself.

Note two things here. First, Kris knows what a hook is. She knows the “rule.” Second, she gives a solid reason for breaking it and mentions, in my view, the most important element—voice.

Let’s look at an example from a surprising source, one Mickey Spillane, in his classic, One Lonely Night.

Mike Hammer novels usually start off like a blast from a .45, in the middle of hot action. But in his fourth Hammer, Spillane breaks his rule because a) he knows exactly why he’s doing it; and b) he could flat-out write. Here’s the opening graph:

Nobody ever walked across the bridge, not on a night like this. The rain was misty enough to be almost fog-like, a cold gray curtain that separated me from the pale ovals of white that were faces locked behind the steamed-up windows of the cars that hissed by. Even the brilliance that was Manhattan by night was reduced to a few sleepy, yellow lights off in the distance.

The mood, the setting, the word choices, the weather (another broken “rule”). The style is immediate and compelling. For the next four pages we have Mike Hammer walking across the George Washington Bridge, thinking.

But what a think it is! It is packed with emotional turmoil that grips and thrashes nothing less than his immortal soul.

He’s thinking about the complete dressing down he got from a judge earlier that day. Hammer was brought in because he’d killed a man, but in self-defense. That didn’t matter to the judge who knew Hammer’s record as a killer of bad guys. Before he lets Hammer out, the judge makes it clear to Hammer and the courtroom that the PI “had no earthly reason for existing in a decent, normal society.”

He had looked at me with a loathing louder than words, lashing me with his eyes in front of a courtroom filled with people, every empty second another stroke of a steel-tipped whip. His voice, when it did come, was edged with a gentle bitterness that was given only to the righteous.

But it didn’t stay righteous long. It changed into disgusted hatred because I was a licensed investigator.

Now, Spillane being Spillane, he knows he can’t stay inside Hammer for a whole chapter. Of course he gets to the action—and man, what action it is!

A girl is running across the bridge, abject fear in her eyes. Someone is after her. Hammer tells her, “Just take it easy a minute, nobody’s going to hurt you.”

A man emerges from the shadows. He’s got his hands in his coat pockets, but clearly has a gun, his “lips twisted into a smile of mingled satisfaction and conceit.” The guy doesn’t realize Hammer carries a .45.

I blew the expression clean off his face.

The action doesn’t end there. The girl screams “as if I were a monster that had come up out of the pit!”

She jumps on the rail and Hammer tries to grab her, but “she tumbled headlong into the white void below the bridge.”

And Hammer is left there with the dead guy’s body, thinking:

I did it again. I killed somebody else! Now I could stand in the courtroom in front of the man with the white hair and the voice of the Avenging Angel and let him drag my soul out where everybody could see it and slap it with another coat of black paint.

He proceeds to search the dead man.

If his ghost could laugh I’d make it real funny for him. It would be so funny that his ghost would be the laughingstock of hell and when mine got there it’d have something to laugh at too.

Finished with the body:

I grabbed and arm and a leg and heaved him over the rail, and when I heard the faint splash many seconds later my mouth split into a grin.

Wow, talk about action. Talk about Spillane’s famous adage The first chapter sells that book. The last chapter sells the next book.

Spillane ends the chapter by connecting back up with the beginning:

I reached the streets of the city and turned back for another look at the steel forest that climbed into the sky. No, nobody ever walked across the bridge on a night like this.

Hardly nobody.

That’s style. That’s voice. That’s how you break a rule. And you can do the same, if you nurture your own voice…and if you first know where to put noses and breasts.

Discuss!

Note: If you want to know how to find and nurture your unique voice, this will help.

Back when Lost became a TV phenomenon, I watched the first season and was just as hooked as everybody else. Man! Each episode ended with an inexplicable and shocking mystery, and I had to keep watching.

Back when Lost became a TV phenomenon, I watched the first season and was just as hooked as everybody else. Man! Each episode ended with an inexplicable and shocking mystery, and I had to keep watching.

We’ve had some robust discussions over the years on this matter of “rules” for writers. That word always seems to raise hackles (hackles, n., the erectile hairs along the back of a dog or other animal that rise when it is angry or alarmed).

We’ve had some robust discussions over the years on this matter of “rules” for writers. That word always seems to raise hackles (hackles, n., the erectile hairs along the back of a dog or other animal that rise when it is angry or alarmed).

Once you wrap your head around the concept of the

Once you wrap your head around the concept of the

There’s a great Far Side cartoon (among so many great ones from the genius Gary Larson). It shows the back of a man seated at a desk. He has a pencil in his fingers, but his hands are grabbing his head in obvious frustration. In front of him are a series of discarded pages with MOBY DICK, Chapter 1 at the top. They say:

There’s a great Far Side cartoon (among so many great ones from the genius Gary Larson). It shows the back of a man seated at a desk. He has a pencil in his fingers, but his hands are grabbing his head in obvious frustration. In front of him are a series of discarded pages with MOBY DICK, Chapter 1 at the top. They say:

The other morning, as is my wont (and I want what I wont when I want it) I took a fresh cup of joe and my AlphaSmart to the backyard for some thinking, pondering, and writing time. The joe was brewed in my moka pot, a gift to mankind from the Italian inventor Alfonso Bialetti. Usually I take it black, but we happened to have some Coffeemate Sweet Italian Cream in the fridge. I thought the key word was Italian, but as it turns out the emphasis should be on sweet. This stuff is a sugar bomb. You need less than a dollop of regular cream. My hand trembled, and I poured in a touch too much.

The other morning, as is my wont (and I want what I wont when I want it) I took a fresh cup of joe and my AlphaSmart to the backyard for some thinking, pondering, and writing time. The joe was brewed in my moka pot, a gift to mankind from the Italian inventor Alfonso Bialetti. Usually I take it black, but we happened to have some Coffeemate Sweet Italian Cream in the fridge. I thought the key word was Italian, but as it turns out the emphasis should be on sweet. This stuff is a sugar bomb. You need less than a dollop of regular cream. My hand trembled, and I poured in a touch too much.

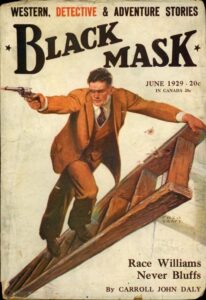

Would there be a Mike Romeo without Race Williams?

Would there be a Mike Romeo without Race Williams?