by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

A little horn toot today as I announce that my tenth Mike Romeo book, Romeo’s Truth, is available for pre-order for Kindle. And at a special deal price, too. (The publisher insisted on this, and after a tense three-hour meeting I agreed to go along with it. Since I am also that publisher, I’ll leave it to the psychologists to figure out what’s going on in my head, a project my wife has been working on for 44 years.)

A little horn toot today as I announce that my tenth Mike Romeo book, Romeo’s Truth, is available for pre-order for Kindle. And at a special deal price, too. (The publisher insisted on this, and after a tense three-hour meeting I agreed to go along with it. Since I am also that publisher, I’ll leave it to the psychologists to figure out what’s going on in my head, a project my wife has been working on for 44 years.)

Ten is always one of those numbers you pause and reflect upon. A tenth anniversary. A tenth child. A tenth bagel. Thus, this series author wonders, wherefore art thou going, Romeo? How long should a series go?

I look at some of the big name series authors and am in awe. As of this post John Sandford has written 36 Prey books (#36 is coming out next year). And 12 Virgil Flowers books. He’s 81 years old and still cranking them out without employing ghost or co-writers or, God help us, AI.

And then there’s Michael Connelly, with 25 Bosch books, 8 Lincoln Lawyers, and 6 Renée Ballards.

(One interesting difference between Lucas Davenport and Harry Bosch is that Sandford has frozen Lucas’s age while Connelly has Bosch aging chronologically with each book, making Bosch about 74. Funny, but in the first Prey book, Rules of Prey, Sandford describes Lucas as having “straight black hair going gray at the temples.” Makes me wonder when Lucas started using Grecian Formula.)

Even dead series authors are still at it. Robert B. Parker is “co-writing” two series, Spenser and Jesse Stone, 15 years after his death. Ditto Vince Flynn, Stuart Woods, Clive Cussler and others.

How can that be? Money, of course. That’s why the traditional publishers of these books perform literary reanimation. It makes complete economic sense.

On the other hand, many a series that doesn’t earn enough dough is dropped, leaving the authors pleading for their rights back, which may or may not happen.

With indie publishing, the author is in full control of the length of a series. Money is a factor, but not the only one. Maybe a series is only making Starbucks scratch but the author still enjoys the writing. (I have no advice to pass along to those who produce by bot. The reward of working hard on a book and nailing it to one’s satisfaction is a joy that cannot be bought by prompt.) Sweating a novel is also fantastic exercise for the brain, which I’d like to keep healthy for the years I have on this orb.

There are also the readers to consider. If they’re pleased, I’m pleased. One reader offered:

“As others have said, this SERIES was hard to put down. The main characters were exciting and not one dimensional at all….I tried to figure out why the plots were so engrossing. There were no chapters…. Just a fast paced, hard hitting story line that flowed from one moment to the next and plot twists that kept one guessing. I hope Mr. Bell writes more in this series.”

Mr. Bell will. I am already at work on Romeo #11. If you’re new to the series, you should know that you can read any of the books as stand-alone thrillers. Romeo’s Truth is a good one to whet your appetite for the others.

If you’re outside the U.S., got to your Amazon store and search for: B0FT6ZR4PJ

As I worked on the last lines of the book, I got that feeling that happens sometimes when an author finishes a project into which they’ve poured blood. A warmth, a palpable satisfaction. And I realized how much I love my characters—Mike, Sophie, Ira, C Dog. It’s that deep affection that comes only when you’ve walked side-by-side with people through a life-threatening crisis (even though it was a crisis of my own making!)

Thanks for listening. Now tell us about a series you love, and why. And if you’re in the midst of writing your own, how are you feeling about it?

Sometimes it’s just plain hard to write. Like when you’re sick. Or feeling drained from a job. I recently went through a season of this, a mix of some medical stuff and general lethargy. For the first time in 25 years, I found myself missing my weekly quota disturbingly often.

Sometimes it’s just plain hard to write. Like when you’re sick. Or feeling drained from a job. I recently went through a season of this, a mix of some medical stuff and general lethargy. For the first time in 25 years, I found myself missing my weekly quota disturbingly often.

Today’s post is about a quandary faced by the writer of a series character. I’m anxious to have a robust discussion with our community of sharp readers and writers about it. Simply put, the problem is love.

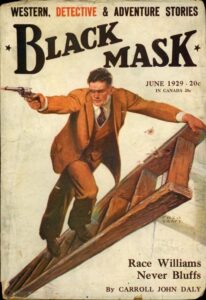

Today’s post is about a quandary faced by the writer of a series character. I’m anxious to have a robust discussion with our community of sharp readers and writers about it. Simply put, the problem is love. Would there be a Mike Romeo without Race Williams?

Would there be a Mike Romeo without Race Williams?