by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Edmund Burke, the eighteenth century member of Parliament known for his rousing speeches, regarded every word in a sentence as “the feet upon which the sentence walks.” He said that to alter a word—exchange it for a shorter or longer one, or give it a different position—would change the whole course of the sentence.

Edmund Burke, the eighteenth century member of Parliament known for his rousing speeches, regarded every word in a sentence as “the feet upon which the sentence walks.” He said that to alter a word—exchange it for a shorter or longer one, or give it a different position—would change the whole course of the sentence.

I thought about that recently while reading a thriller. It was good on the plot and character levels (which are, of course, absolutely essential). It started off like gangbusters, and carried me through the first three chapters.

But as it went on, I found myself without that feeling of compulsion to keep reading, as one has with the best fiction experiences. I wasn’t in a rush to turn the page. Naturally, as a writer and teacher of writing, I paused to ask myself why.

The answer came to me almost immediately. The sentences were all merely functional. They were like Dutch furniture. They did their job, but nothing more. I’ve quoted this many times, but it’s worth repeating. John D. MacDonald, writing about what he looks for in an author (including himself), said, “I want him to have a bit of magic in his prose style, a bit of unobtrusive poetry. I want to have words and phrases that really sing.”

Is that something worth going for? I think it is. MacDonald rose to the top of the mass market heap in the 1950s in part because his writing was a cut above what one critic called the “machine-like efficiency” of his contemporaries.

So let’s have a look at things you can do to make some of your sentences sing.

Rearrange

Consider this as the first line of a novel:

The small boys came to the hanging early.

Okay, fine. It works. But what if we did it the way Ken Follett does it in The Pillars of the Earth:

The small boys came early to the hanging.

Feel the difference? On a subconscious level, it elevates the effect. Hanging is the most vivid word, and putting at the end gives the sentence snap and verve. A novel with sentences like that can mean the difference between a good read and an unforgettable one.

Overwrite And Cut

When I get to an intense emotional moment, I like to pause and start a text doc and write a page-long sentence. I just go, putting down everything I can think of without pausing to edit. As an example, here’s an actual sentence from John Fante’s classic Ask the Dust, in the voice of a young writer named Arturo Bandini in 1930s Los Angeles.

A day and another day and the day before, and the library with the big boys in the shelves, old Dreiser, old Mencken, all the boys down there, and I went to see them, Hya Dreiser, Hya Mencken, Hya hya: there’s a place for me, too, and it begins with B, in the B shelf, Arturo Bandini, make way for Arturo Bandini, his slot for his book, and I sat at the table and just looked at the place where my book would be, right there close to Arnold Bennett, not much that Arnold Bennett, but I’d be there to sort of bolster up the Bs, old Arturo Bandini, one of the boys, until some girl came along, some scent of perfume through the fiction room, some click of high heels to break up the monotony of my fame.

Write something like that, and keep going. Then you rest a bit, come back to it, and choose the best parts. It might just be one sentence, but it will be gold and will make your book glitter.

Cutting Adverbs

Sometimes a sentence sings best when it’s lean. Which brings us to the subject of adverbs.

Stephen King said, “The road to hell is paved with adverbs.”

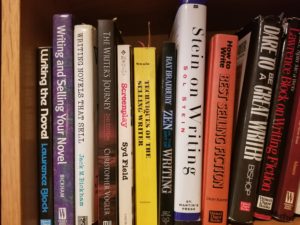

In Stein on Writing, Sol Stein advises cutting all the adverbs in a manuscript, then readmitting only “the necessary few after careful testing.”

That’s good advice, and not hard to follow. Do a search for –ly words and see if you can’t cut the adverb or find a stronger verb.

Be especially (!) vigilant with dialogue tags. Elmore Leonard (who is quoted much too often these days, he said solemnly) called using an adverb to modify said a “mortal sin.” Perhaps a venial sin. I’m not a Robespierre about this, sending all adverbs to the guillotine. But do make them state their case before you “sentence” them.

Resonance at the End

The last sentences of your book are the most important of all. They may be the ones that get the reader to order another of your books immediately, as opposed to ho-humming and finding something else to read.

One of the most famous ending sentences in American Lit is from the short story that put William Saroyan on the map. “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze” was published in 1934, the height of the Depression. It’s the story of young writer who is starving to death. He walks the streets, looking for work, but there’s nothing for him. He’s down to one penny. He returns to his room, becomes drowsy and nauseous. He falls on his bed, thinking he should give the penny to a child, for a child could buy any number of things with a penny. The story ends:

Then swiftly, neatly, with the grace of the young man on the trapeze, he was gone from his body. For an eternal moment he was all things at once—the bird, the fish, the rodent, the reptile, and man. An ocean of print undulated endlessly and darkly before him. The city burned. The herded crowd rioted. The earth circled away, and knowing that he did so, he turned his lost face to the empty sky and became dreamless, unalive, perfect.

That one word—unalive—is not in the dictionary. But who cares? It’s meaning is obvious. Saroyan could have written dead, but that wouldn’t have any zing. And the word perfect at the end is so surprising given the context that it leaves us pondering, feeling, perhaps even weeping. In other words, there’s resonance, that final, haunting note hanging in the air after the music stops.

Man, oh man, that’s worth reaching for.

Brother Gilstrap has written about the importance of last lines. His favorite is from To Kill a Mockingbird:

He turned out the light and went into Jem’s room. He would be there all night, and he would be there when Jem waked up in the morning.

Another resonant ending is from The Catcher in the Rye:

It’s funny. Don’t ever tell anybody anything. If you do, you start missing everybody.

And this, from my favorite Bosch, Lost Light:

I leaned forward and raised her tiny fists and held them against my closed eyes. In that moment I knew all the mysteries were solved. That I was home. That I was saved.

My advice is to write your last few sentences several times. Each time, say them out loud. How do they sound? How do they make you feel? Go for the heart. Teach them to sing.

Discuss!