Since it’s Valentine’s Day tomorrow, tell us what your favorite love story is, book or movie (or both). It can be a romance or have a romantic subplot. Mine:

Since it’s Valentine’s Day tomorrow, tell us what your favorite love story is, book or movie (or both). It can be a romance or have a romantic subplot. Mine:

Movie: It Happened One Night.

Book: Rebecca.

Since it’s Valentine’s Day tomorrow, tell us what your favorite love story is, book or movie (or both). It can be a romance or have a romantic subplot. Mine:

Since it’s Valentine’s Day tomorrow, tell us what your favorite love story is, book or movie (or both). It can be a romance or have a romantic subplot. Mine:

Movie: It Happened One Night.

Book: Rebecca.

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Some questions for you today as we consider what we write and what readers want from our writing.

Some questions for you today as we consider what we write and what readers want from our writing.

A book recently showed up on Project Gutenberg called Plotting the Short Story. It was published in 1922, just as the golden age of pulp was taking off. And while its focus was on short-form writing, I found much of what it said relevant to full-length. Let’s have a look:

The modern short story calls for speed and snap. We have made this remark before, but, if one is to judge by the number of spineless manuscripts that swell the average editor’s daily mail, it will bear repetition many times. The story must be placed before the reader with trip-hammer strokes. Readers who seek mental relaxation in short stories are usually busy people who read in much the same manner that they eat—“quick-lunch” style. They have not the time to wade through pages of rambling descriptive matter or absorb weighty paragraphs of philosophic reflection. They refuse to be instructed; they want to be amused, and like their stories served up piping hot, as it were.

Don’t you think that still hold true? Certainly people are busier than ever. The year 1922 seems positively soporific compared to today. And consumers of commercial fiction still “seek mental relaxation” (which is another way of saying don’t make them work too hard to figure out what’s going on, or wear them out with “weighty paragraphs.” (See Pat’s post and the comments thereto).

On method:

There are a great many writers, of course, especially among those who have “arrived,” who do not find it necessary to commit their plots to paper, but who work them out in their minds before they begin their stories, or build them up detail by detail after their stories are begun. To these writers, plot balance and movement have become instinctive, and they find that their words flow easier and that their imaginations are more active when they begin their stories with only a half-formed plot in mind or, indeed, with no plot at all, their theory being, that the creative mental powers are given fuller play if permitted to invent while the story itself is in the process of development than if forced to form a fixed plot-plan before the story has begun to materialize.

Your dedicated panster could not have put it more elegantly. But a word of warning:

But in the main these writers rely upon word-grouping (style) more than upon plot to put their stories “over,” and even the best of those who adopt this policy occasionally come to grief, for it is not an easy matter to fashion a plot and beautifully formed word groups at one and the same time. Such a plan, if consistently followed, usually proves fatal to the beginner.

A technically-correct plot upon which to build one’s story is as essential to success as a thorough understanding of the language of one’s country; and the only way for the novice to make sure his plots are free from technical flaws is for him to work them out on paper, according to fixed rules, with the same care that he would use in solving a knotty mathematical problem.

This describes my own journey. I was a free-flowing pantser at first, traipsing joyfully in the meadows of my imagination each day, trusting that it would lead to the kinds of stories I loved to read. It didn’t.

Authors…should therefore make an exhaustive study of the plot, calling to their aid several authoritative text books in order to get the teacher’s point of view, and analyzing the stories they read in the current magazines so they can get a line on the plot as it is handled by successful writers, and at the same time become acquainted with the editorial preferences of the different periodicals.

So I started to study, diligently, and apply what I was learning to my writing. Then I started to sell. Thus, I do believe getting foundational plot principles into a writer’s “muscle memory” will save them years of frustration:

Once the simple rules of plot construction become fixed in his mind, and he gets the feel of the plot, the writer can begin a story with nothing to build on but a vague idea and a burning desire with some hope of working out a well-proportioned plot after the story is well under way, but until he does master these rules he courts disaster each time he begins a story unless he has worked out his plot in advance.

Toward the end, the author states:

Enthusiasm is the chief requisite in plot making.

That is, plot principles alone aren’t enough. To this must be added—

—a spark…that starts a conflagration in the writer’s brain and makes him an object to be pitied until he sits down before his typewriter and pounds out a story to make us sit up half the night to read.

A machine can construct a plot. It can even produce “competent” fiction. But as Brother Gilstrap recently put it, “Stories need to be more than conduits for plots and twists. Books we love connect with us emotionally because a human author infused that emotion into their work.”

All of it works together—plot, speed, snap, spark. You must learn them through experience, and without an aversion to that little word work.

Comments welcome.

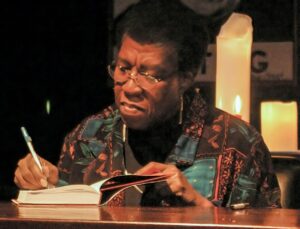

“I tell would-be writers that there are three things to forget about. First, talent. I used to worry that I had no talent, and it compelled me to work harder. Second, inspiration. Habit will serve you a lot better. And third, imagination. Don’t worry, you have it.” — Octavia Butler

“I tell would-be writers that there are three things to forget about. First, talent. I used to worry that I had no talent, and it compelled me to work harder. Second, inspiration. Habit will serve you a lot better. And third, imagination. Don’t worry, you have it.” — Octavia Butler

What are your thoughts on the mix of talent, work, and imagination?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner had a routine called The 2000-Year-Old Man. Reiner played a reporter interviewing the world’s oldest man, who would tell him all sorts of things that happened in the distant past. One time the subject was religion:

Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner had a routine called The 2000-Year-Old Man. Reiner played a reporter interviewing the world’s oldest man, who would tell him all sorts of things that happened in the distant past. One time the subject was religion:

REINER: Did you believe in anything?

BROOKS: Yes, a guy, Phil. Philip was the leader of our tribe.

REINER: What made him the leader?

BROOKS: Very big, very strong, big beard, big arms, he could just kill you. He could walk on you and you would die.

REINER: You revered him?

BROOKS: We prayed to him. Would you like to hear one of our prayers? “Oh Philip. Please don’t take our eyes out and don’t pinch us and don’t hurt us. Amen.”

REINER: How long was his reign?

BROOKS: Not too long. Because one day, Philip was hit by lightning. And we looked up and said, “There’s something bigger than Phil.”

I’ll return to this later.

I was too busy to give a thoughtful reply to Terry’s post about Amazon and their new “Ask This Book” feature. Enough has been said about it there—and everywhere—that the issues are clear.

Most pressing for authors and publishers are copyright and permission. Does this feature, which provides plot summaries and character analyses, violate copyright? Or is it more like a flexible version of CliffsNotes?

Or is ATB different in kind? The Authors Guild thinks so. It argues that what Amazon is doing is creating an interactive book from the original material, i.e., another iteration of an author’s intellectual property, for which the author should receive compensation. I suspect there is a lot more to come on this matter.

It should be noted that someone can go straight to AI now and ask for a summary and analysis of a book. I went to Grok and asked for a summary of a thriller by one of my favorite authors. I got it. Accurately, too. Without spoilers. When I asked specifically for the spoiler answer to the ultimate mystery, I got that, too. I then asked for an analysis of the main characters. Check. (In deference to the author, from whom I did not seek permission, I will not post the answers.) Is ATB merely a more convenient way for a reader to get the same information?

And speaking of permission, this feature is being rolled out by Amazon without giving the author or publisher the choice to opt in or out, as with DRM. This has raised the temperature in many a discussion. Given that, what should an author do? I don’t think many will pull their ebooks off Amazon in protest, because Amazon is their biggest revenue stream. It’s irrelevant whether one is wide or exclusive.

Which brings me back to Phil. Because there’s something bigger than Amazon in all this. And that is Artificial Intelligence itself. We all know it’s here, it’s growing, and it’s here to stay. There have been innumerable discussions, debates, and jeremiads on how writers use this borg. For me, the firm no-go zone is having it generate text that is cut-pasted into a book, even though AI can now replicate a writer’s particular style (see Joe Konrath’s recent post and the examples therein).

What I’m most concerned about is the larger issue of melting brains. Using AI as a substitute for hard thinking atrophies the gray matter. “Use it or lose it” is real. In the past, a reader who wanted to know what’s happened in a book had to “flip back” actual pages to find out. That was work, and therefore good for the noggin. AI bypasses that neural network.

This brain rot is bad for the species, especially among the young. It tears my heart out to see a man or woman walking down the street, looking at their phone, while pushing a stroller with a toddler in it, who is likewise staring at a device full of dancing monkeys or pink rabbits. That child’s brain is being robbed of essential foundations built only by looking around at the real world in wonder.

The school years used to be a daily session of ever more complex thinking. Learning to write a persuasive essay—with a topic paragraph and supporting arguments—was once a major goal of education. Now AI can do that for you in seconds, so you can go back to playing Candy Crush.

We all know this. But what can we do about it? Take responsibility for our own actions. Don’t let AI do all the work for us, or for our kids and grandkids.

And if you’re upset with Amazon’s ATB, cool your jets and register a polite response to KDP customer service. There’s enough vitriol out there. We’re awash in so much Ghostbusters II mood slime now that we don’t need to add to it.

Because as bad as brain rot is, soul rot is worse. And a hate-laced, click-bait habit will inevitably turn your soul into the picture of Dorian Gray. Don’t go there.

And those are my myriad thoughts. Help me sort them out in the comments.

Here’s an oldie from TKZ emerita Jordan Dane:

Answer any one or all:

1.) What’s your favorite way to select a character’s name? (Do you have any favorite GO TO resource links?)

2.) Do you care about name origins or meanings?

3.) How do you select names for a character with different ethnic backgrounds?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Today’s post is brought to you by Romeo’s Way. Yes, with Romeo’s Way you’ll be the envy of every reader on the block. And for a limited time only, Romeo’s Way can be yours for the low, low price of 99¢.

No on to our blog and your host, JSB!

In the early years of television, most shows had a single sponsor paying the bills, e.g., Colgate Comedy Hour, Texaco Star Theatre, Goodyear TV Playhouse, Kraft Television Theatre. The shows that were “brought to you by” often featured the stars in a commercial.

“Father Knows Best, brought to you by Maxwell House Coffee. Good to the last drop.”

“Leave it to Beaver has been brought to you by Ralston Purina, makers of the eager eater dog food.”

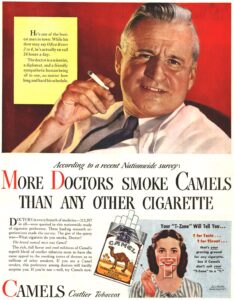

“The Fugitive has been brought to you by Viceroy cigarettes. Viceroy’s got the taste that’s right.”

Speaking of that ubiquitous weed, a plethora of shows were sponsored by tobacco companies.

companies.

The sponsors hoped the brand would be associated with a quality show and its stars, week after week. Not just quality, but consistent quality, directed to a target audience.

The most popular show of 1953 was I Love Lucy. It worked because Lucille Ball was a brilliant comedic actress, Desi Arnaz a perfect foil and also an astute producer.

The second most popular show that year was Dragnet, the very opposite of Lucy. A police drama, it had a consistent style developed by its star, Jack Webb. That style featured staccato dialogue and underplayed acting. It became famous and easily parodied. (Fortunately, Jack Webb had a sense of humor about it.)

There have been innumerable articles for writers about developing their “brand.” What that is is not really complicated. It’s an expectation in readers’ minds about what you, the author, can deliver to them. It’s a mash up of the type of books you write, your voice, your visuals (book covers, website, etc.) and your online presence. What you want to communicate is that you are capable of producing work of consistent quality. You want to be seen as a “trusted brand.” This is why traditional publishing invests in promising new writers. They hope to create a long-term, profitable “product line.”

Now, what if a writer wants to write something “off brand”? In the traditional publishing world, this is problematic, for obvious commercial reasons. The brand helps bookstores know where to shelve your books. It is protection for the publisher’s investment.

This is what hamstrung early John Grisham, whose massively popular legal thrillers made big bucks for all. But Grisham wanted to write literary fiction, too. It was only when he had sufficient leverage that he was “allowed” to write A Painted House.

Indie writers have more flexibility, though they want to build a brand, too. But if they hanker to try something a little different, why not? The world’s largest bookstore will “shelve” your book in the right places (categories). So JSB can offer thrillers, historical fiction, even crime fighting nun stories, and not miss a meal.

The most important part of a brand is delivering the goods. That’s what you want your name to be associated with. All of the razzle dazzle of covers and marketing and ads might get you a look from an interested buyer. What you want is to entice them to come back for more.

When Lay’s Potato Chips were introduced in the 1960s, they ran an ad campaign featuring Bert Lahr (of Cowardly Lion fame). He’s reading the paper when his little boy comes in with an open bag of Lay’s. He asks the boy what that is. The boy says, “Lay’s Potato Chips. I bet you can’t eat one.” Burt takes a chip, eats, tells his son to go do his homework…but then the taste kicks in and he says, “I’ll have another.” The boy says, “Uh-uh, I said one.” At which point Bert grabs the bag and starts munching chip after chip. The boy turns to the camera. “I knew he couldn’t do it.”

The Lay’s tagline: “No one can eat just one.”

This is the hope of all series writers, too!

Thank you for reading today’s post, brought to you by Romeo’s Way, the thriller that builds strong bodies twelve ways. Nine out of ten doctors who read thrillers prefer Mike Romeo.

Do you have an author brand? How would you describe it?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I believe it was the writer-director John Huston who once said a great movie has three unforgettable scenes, and no weak ones. Makes sense to me. Maybe that’s the difference between a good book and a great book, a fine read and an unforgettable one. Let’s think about it.

I believe it was the writer-director John Huston who once said a great movie has three unforgettable scenes, and no weak ones. Makes sense to me. Maybe that’s the difference between a good book and a great book, a fine read and an unforgettable one. Let’s think about it.

Huston wrote and directed many great films (let’s not talk about Annie. Why Ray Stark tapped Huston to direct his first and last musical, I’ll never know). One of my favorites is The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) starring Humphrey Bogart, Tim Holt and John’s dad Walter Huston (who took home the Best Supporting Actor Oscar). It’s a stark, noirish drama set in Mexico. The first unforgettable scene (for me) is a brutal fight in a bar, when Bogart and Holt confront the man who owes them money. It’s brilliantly choreographed, and done without musical score.

And then there’s a scene that is with us today, whenever anybody utters the line, “Batches? We don’t need no steenking batches!”

I also love the scene where Walter Huston dances around calling out Bogart and Holt. “You’re dumber than the dumbest jackass! Look at each other, will ya? Did you ever see anything like yourself for bein’ dumb specimens? You’re so dumb, you don’t even see the riches you’re treadin’ on with your own feet. Yeah, don’t expect to find nuggets of molten gold. It’s rich but not that rich. And here ain’t the place to dig. It comes from someplace further up. Up there, up there’s where we’ve got to go. Up there!”

Let’s talk thrillers. Let’s talk The Silence of the Lambs.

There’s the first time Clarice meets Lecter. When I saw the movie I felt a distinct chill throughout my body as Clarice first approaches Lecter’s cell in the bowels of the prison. We watch from her POV and she first lays eyes on him.

He’s just standing there, looking like Anthony Hopkins, in a position that’s hard to describe. It’s almost like he’s at attention, but with the slightest smile that is full of mystery and menace. It just radiated off the screen. And then begins the cat-and-mouse game that is almost ten minutes of pure tension, primarily through dialogue (as in the book as well).

Quieter movies or books need those unforgettable scenes, too. To Kill a Mockingbird has several to choose from. There’s the cross-examination of Mayella Ewell (the movie version is enhanced by the knockout performance by Collin Wilcox as Mayella). At the end there’s the revelation of Boo Radley (brilliantly portrayed by a young Robert Duvall).

And then there’s the scene at the jail where Atticus faces a lynch mob, and the scene takes a most unexpected turn. See for yourselves:

It’s no undiscovered writing tip to say that we ought to strive for unforgettable scenes. Some writers don’t think about it. They just go from scene to scene doing the best they can with them. I prefer to be more intentional.

One of the things I used to do (before Scrivener came on the scene) was take a pack of 3×5 cards to a local coffee establishment and start brainstorming “killer scene” ideas for my upcoming project. I didn’t pre-judge. I just wrote and looked at the cards later. I remember writing cards for my first Ty Buchanan legal thriller, Try Dying. I had this “vision” of Ty getting on a conference table and tap dancing. Wait, what? But it fit in the book as Ty, whose fiance was killed on page one, is in the conference room of a big-time lawyer trying to intimidate him:

I grabbed my notes and stuffed them in my briefcase. With a quick step on the chair I jumped onto the conference table. As Walbert’s eyes opened wider, I did a little three-step tap dance.

“What are you doing?” he howled.

“Gene Kelly,” I said.

“Get off that table!”

“This is what it’s going to be like, Barton. You looking up at me from now on.”

His face changed colors. Cheeks rosy like the dawn. I don’t know why I did it, except that I never liked bullies. On the schoolyard or in a plush conference room.

Gerry Spence, the greatest trial lawyer of his day, was once asked on 60 Minutes what he’d have done if he were a cowboy in the old West, facing a guy with a knife. “I’d leave him bloody on the floor,” Spence said, “which is the way I try cases.”

I jumped off the table and said, “See you in court, Barton. I’m going to leave you bloody on the floor.”

Let your imagination run wild, without judgment. That’s how you get the gold. That’s what Walter Huston would say. He’d point to your head. “Up there’s where you’ve go to go. Up there!”

How about you? What scenes do you remember from books or movies that were unforgettable?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I have been musing about something of late. Call it a typology of writers. Here the categories I’ve come up with, recognizing there will be some overlap. Let’s discuss.

1. Nothing But Fun

There are some writers who believe writing fiction should be nothing but a joy, carefree, never a matter of sweat or concern. Under this category, there are two sub types. The first believes that a carefree first draft is the only draft it should be written. Cleaned up a bit for typos, perhaps, but left mostly alone. The other subtype writes that first draft and then looks at it and wonders what the heck to do with it, and tries to apply some actual craft and editing.

2. Hate Writing, But Love Having Written

I know a few colleagues who fit this category. They find writing a first draft to be a somewhat difficult trudge. Sometimes this is because their standards go up with each book. The bar is raised. And they seriously want to meet that challenge.

But when they are done with the whole process, including editing and polishing, and the book is the better for it, they find tremendous satisfaction.

3. Lunchpail Type

This is a writer who goes to work each day. They’re not looking for a rapturous experience, though that may happen when they’re not looking. They set out to write a certain number of words each day and do that job. They know their craft and care about it, because they want to sell to readers, and readers care about good stories. The great pulp writers of old were like this. They could type 1 million words a year, sometimes more, and sell their product for a penny or two per word.

4. Doesn’t Care About Sales

In truth, I think every writer cares about sales. Who wouldn’t appreciate a little green from what they write? There’s that famous Samuel Johnson quote: “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.” But this type of writer rejects that notion and finds their satisfaction in writing alone. Nothing wrong with that. Writing can be a form of enjoyment, diversion, mental exercise, or escape.

5. Only Cares About Sales

Finally, there is the writer who is in this strictly for the money. There’s never been anything illegal about that. If somebody write something and there’s a market for it, that’s a fair exchange. But these days it’s possible to make money producing acres of “AI slop.” We all wish this weren’t true, but it is. This type shouldn’t even be categorized as a “writer.”

On the other hand, someone who sees writing as a way to make money, or at least side-hustle dough, and works to figure out how to write a good product, fine. I suspect this is the least populated category.

In reviewing this list, I would put myself as a #3. I’ve always written to a quota. I have also found tremendous satisfaction in learning my craft and getting better at it.

So what do you think about the above categories? Would you add one? Modify one? Where would you place yourself?