“You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.” – Ray Bradbury

Does this still apply? Is it irrelevant in the age of the machine, or more important than ever?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Jackie Gleason, Paul Newman in The Hustler (1961)

When I teach at a writers conference I’ll often show a clip from one of my favorite movies, The Hustler (1961), starring Paul Newman, George C. Scott, Piper Laurie, and Jackie Gleason. It’s the story of “Fast Eddie” Felson (Newman), a pool hustler who longs to beat the best player in the world, Minnesota Fats (Gleason).

Stuff happens (this is what’s called a short synopsis). Bert Gordon (Scott), who manages Fats, labels Eddie “a loser.” This gets under Eddie’s skin. One day he asks his girl, Sarah, if she thinks he’s a loser. She is taken aback. He says he lost control the night he went hustling and got mad at the arrogant kid he was playing. “I just had to show those creeps and those punks what the game it like when it’s great, when it’s really great.” He explains that anything, even bricklaying, can be great if “a guy knows how to pull it off.” He tells Sarah what he feels “when I’m really going.”

It’s like a jockey must feel. He’s sittin’ on his horse, he’s got all that speed and that power underneath him, he’s comin’ into the stretch, the pressure’s on ’im, and he knows! He just feels when to let it go and how much. ’Cause he’s got everything workin’ for him, timing, touch…it’s a great feeling, boy, it’s a real great feeling when you’re right and you know you’re right. It’s like all of a sudden I got oil in my arm. The pool cue’s part of me. You know, it’s a pool cue, it’s got nerves in it. It’s a piece of wood, it’s got nerves in it. You feel the roll of those balls, you don’t have to look, you just know. You make shots nobody’s ever made before. I can play that game the way nobody’s ever played it before.

Sarah looks at him and says, “You’re not a loser, Eddie, you’re a winner. Some men never get to feel that way about anything.”

Give thanks you’re a writer. We experience life in all its colors—joy, doubts, hopes, frustrations, wins, losses, knockdowns and comebacks. We work at our craft and get better, and start to make “shots” we’ve never made before. A writer of any genre can make a book great—from pulp to literary, romance to thriller, chicklit to hardboiled. And when you pull it off, you feel like pool felt to Fast Eddie. That’s winning, because some people never feel that way about anything.

Some years ago I wrote a takeoff on Clement Clarke Moore’s famous poem, “The Night Before Christmas.” I offer it to you once more as we sign off for our annual two-week break. Heartfelt thanks to all of you for another great year here at TKZ!

’Twas the night before Christmas, and all through the room

’Twas the night before Christmas, and all through the room

Was a feeling of sadness, an aura of gloom.

The entire critique group was ready to freak,

For all had rejections within the past week.

An agent told Stacey her writing was boring,

Another said Allison’s book left him snoring.

From Simon & Schuster Melissa got NO.

And betas agreed Arthur’s pacing was slow.

“Try plumbing,” a black-hearted agent told Todd,

And Richard’s own mother said he was a fraud.

So all ’round that room in a condo suburban

Sat writers––some crying, some knocking back bourbon.

When out in the hall there arose such a clatter,

That Heather jumped up to see what was the matter.

She threw the door open and stuck out her head

And saw there a fat man with white beard, who said,

“Is this the critique group that I’ve heard bemoaning?

That keeps up incessant and ill-tempered groaning?

If so, let me in, and do not look so haughty.

You don’t want your name on the list that’s marked Naughty!”

He was dressed all in red and he carried a sack.

As he pushed through the door he went on the attack:

“What the heck’s going on here? Why are you dejected?

Because you got criticized, hosed and rejected?

Well join the club! And take heart, I implore you,

And learn from the writers who suffered before you.

Like London and Chandler and Faulkner and Hammett,

Saroyan and King––they were all told to cram it.

And Grisham and Roberts, Baldacci and Steel:

They all got rejected, they all missed a deal.

But did they give up? Did they stew in their juices?

Or quit on their projects with flimsy excuses?”

“But Santa,” said Todd, with his voice upward ranging,

“You don’t understand how the industry’s changing!

There’s not enough slots! Lists are all in remission!

There’s too many writers, too much competition!

And if we self-publish that’s no guarantee

That readers will find us, or money we’ll see.

The system’s against us, it’s set up for losing!

Is it any surprise that we’re sobbing and boozing?”

“Oh no,” Santa said. “Your reaction is fitting.

So toss out your laptops and take up some knitting!

Don’t stick to the work like a Twain or a Dickens.

Move out to the country and start raising chickens!

But if you’re true writers, you’ll stop all this griping.

You’ll tamp down the doubting and ramp up the typing.

You’ll write out of love, out of dreams and desires,

From passions and joys, emotional fires!

You’ll dive into worlds, you’ll hang out with heroes.

You’ll live your lives deeply, you won’t end up zeroes!

And though you may whimper when frustration grinds you

There will come a day when an email finds you.

And it will say, ‘Hi there, I just love suspense,

And I found you on Kindle for ninety-nine cents.

I just had to tell you, the tension kept rising

And didn’t let up till the ending surprising!

You have added a fan, and just so you know,

If you keep writing books I’ll keep shelling out dough!’

So all of you cease with the angst and the sorrow,

And when you awaken to Christmas tomorrow,

Give thanks you’re a writer, for larger you live!

Now I’ve got to go, I’ve got presents to give.”

And laying a finger aside of his nose

And giving a nod, through the air vent he rose!

Outside in the courtyard he jumped on a sleigh

With eight reindeer waiting to take him away.

At the window they watched him, the writers, all seven,

As Santa and sleigh made a beeline toward Heaven.

But they heard him exclaim, ’ere he drove out of sight,

“Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good write!”

See you in 2026!

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Tim Holt, Walter Huston, Humphrey Bogart in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

The other day I woke up early, as is my wont, and set about working on my WIP, Romeo #11. The day before I’d finished a scene I loved, and as I looked it over I heard that little voice whispering, “Kill your darlings.” I’ve written about that before. Give a darling a hearing, at least.

The scene ended with action. What I needed now was Mike’s reaction to it. A “sequel” in Dwight Swain terms. Swain was the author of one of the great craft books, Techniques of the Selling Writer. I go over it once a year. Swain held there are two major beats in fiction, scene and sequel. A scene is the action that takes place, with obstacles (conflict) and, in commercial fiction, usually a set-back (he called this a “disaster”). The sequel is the emotional reaction to the disaster, followed by an analysis of the situation and a decision about what action to take next.

It makes sense. When we get slapped down our first reaction is not, “Well now, that was interesting. Let me think about it.” No, we react with raw emotion. The bigger the disaster, the bigger the emotion. Not all setbacks are a 10 on the disaster scale. Sometimes, you don’t need a long sequel. The character can’t find his reading glasses. Darn! That’s sequel enough. But if his wife is blown up by a car bomb (as in the classic film noir The Big Heat) there’s going to be a huge sequel.

You thus render a sequel commensurate with the disaster. If small, you can do it in one line or even one word. Or sometimes skip it and let the action do the talking (He slapped his forehead. And found his glasses).

How you handle scene and sequel determines how your book “feels” to the reader.

The more you emphasize scene, the more you move into the “plot-driven” camp. Some of these have no sequel at all, which makes the books as hardboiled as a twenty-minute egg (see, e.g., the Parker novels of Richard Stark, nom de plume of Donald Westlake).

The more you emphasize sequel, the more you move toward “character-driven” fiction; further still, and you’re closing in on “literary fiction.” Again, these are generalities, but the lesson is clear: the handling of sequel is crucial to the craft.

Indeed, Jim Butcher, author of the Harry Dresden series, is thought of as a plot-driven guy, and not without reason. But he believes sequels “make or break books.”

You’ve got to establish some kind of basic emotional connection, an empathy for your character. It needn’t be deep seated agreement with everything the character says and does–but they DO need to be able to UNDERSTAND what your character is thinking and feeling, and to understand WHY they are doing whatever (probably outrageous) thing you’ve got them doing. That gets done in sequels.

His breakdown:

1) Scene–Denied!

2) Sequel–Damn it! Think about it! That’s so crazy it just might work!–New Goal!

3) Next Scene!

Repeat until end of book.

Now, my Mike Romeo books are not, by intention, purely hardboiled. I think about sequels a lot.

And that’s where I was on the morning in question. I needed a sequel to the action. But what should it consist of?

Here’s a secret: don’t just grab the first emotion that comes to mind. That’s usually the one readers expect. Avoiding the predictable is essential to page-turning fiction.

So there I was, in Scrivener, wondering what Mike’s reaction should be. So in the notes section, I started writing…and writing….in Mike’s voice….until he started telling me something I hadn’t anticipated. Boom! There it was, the right sequel.

When I get to a moment of big emotion, I usually open up a fresh text doc, or use the Scrivener notes panel, and overwrite, just letting the words pour out until I get to a fork in the road and, like Yogi Berra used to counsel, take it. I write metaphors in fast bunches, like candies on the conveyor belt in that famous I Love Lucy episode. (“Speed it up a little!”).

I’ll write 200, 300 words. And then I pan for gold. Even if it’s just one line that sparkles, I’ll polish it up and use it. This is the “work” of a writer, which some sniff at as being too much effort. I choose to go for the gold.

How about you?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

We all know that various tasks, assessments, creations, observations, and reactions trigger different parts of the brain. For example, the other day I was driving along on a busy, two-lane street near my home, enjoying the nice day and the classical music station on the radio, when a loud VROOM blasted next to me and instantly put me into “fight or flight” mode, as some idiot in a Mustang shot past all the cars by racing on the median strip, then darting back into traffic like he was playing a video game, then went out again to pull the same stunt. A bad accident waiting to happen, which is old news here in L.A.

We all know that various tasks, assessments, creations, observations, and reactions trigger different parts of the brain. For example, the other day I was driving along on a busy, two-lane street near my home, enjoying the nice day and the classical music station on the radio, when a loud VROOM blasted next to me and instantly put me into “fight or flight” mode, as some idiot in a Mustang shot past all the cars by racing on the median strip, then darting back into traffic like he was playing a video game, then went out again to pull the same stunt. A bad accident waiting to happen, which is old news here in L.A.

Anyway, when it comes to creation, we have a “team” consisting of the imagination group, the analytical staff, and the Boys in the Basement. They band together on our projects, and as we work in tandem with our good ol’ noodle (for you youngsters, noodle is old-school slang for head, which is derived from the 1500s word noddle—which in Old English meant head resting on a neck—and some smart aleck in the 1700s who added the “oo” sound from fool. I also could have chosen nut, noggin, or dome. Take note, as there will be a quiz on this later) we exercise our brains, which is essential for our overall health.

Which is why handing off all creative effort to AI is like preparing for a long distance race by eating Twinkies. The long term effect is horrible, especially in young brains that are still developing. Yes, AI can be an aid in some situations, but there should be a flashing Approach With Caution sign at every turn.

Now, there are different kinds of writing that work out the various parts of the gray matter— fiction, essays, poetry, jingles, marketing copy, letters (remember letters? That you write in your own hand and put in an envelope? That took some care, unlike the emails we send every day and the texts we fire off like so much digital buckshot) and anything else that requires a modicum of thought.

I consider myself a writer. I write. That’s all I ever wanted to do. I specialize in that form of fiction called the thriller. It’s my bread and butter—in fact, it butters my bread—and it is my primary focus. But when I engage in another type of writing I find that my overall creative muscle is improved, and I feel that when I go back to fiction.

That’s why I started a Substack. It’s my foray into a type of nonfiction I call “Whimsical Wanderings.” These are free-range essays without fences. I spend part of my early mornings playing in this part of my brain, and bring order to it later. Ray Bradbury once said of his own writing, “Every morning I jump out of bed and step on a landmine. The landmine is me. After the explosion, I spend the rest of the day putting the pieces together.” I can relate.

And now, gentle reader, I am happy to solve a problem for you. With the holiday season upon us, some of you may be scratching your head about what to get for that certain someone you find it so hard to get things for. What gift is suitable, surprising, fun, and relatively cheap? Now you have it. The best of Whimsical Wanderings is contained in the collection Cinnamon Buns and Milk Bone Underwear, the print version of which is available for purchase at the special intro price of $9.99 (that’s the lowest price Amazon will allow for this book. In a week it’ll go to $15.99, at which time I’ll start announcing it to the world at large, including Albania). You may get it here. There’s also the ebook version at the low end of $2.99, here. If I may offer a blurb:

And now, gentle reader, I am happy to solve a problem for you. With the holiday season upon us, some of you may be scratching your head about what to get for that certain someone you find it so hard to get things for. What gift is suitable, surprising, fun, and relatively cheap? Now you have it. The best of Whimsical Wanderings is contained in the collection Cinnamon Buns and Milk Bone Underwear, the print version of which is available for purchase at the special intro price of $9.99 (that’s the lowest price Amazon will allow for this book. In a week it’ll go to $15.99, at which time I’ll start announcing it to the world at large, including Albania). You may get it here. There’s also the ebook version at the low end of $2.99, here. If I may offer a blurb:

Every time one of James Scott Bell’s Whimsical Wanderings arrives in my email box, I smile, even before I open it. Each post takes me down a path I am not expecting but am so glad for the journey by the time I reach the end. If you want to lift your spirits while being surprised by how one thought can lead to another, treat yourself to this book! — Robin Lee Hatcher, Christy Award winning author of The British Are Coming series

End of commercial. I’ll leave you with this from Malcolm Bradbury, in Unseen Letters: Irreverent Notes From a Literary Life:

I write everything. I write novels and short stories and plays and playlets, interspersed with novellas and two-hander sketches. I write histories and biographies and introductions to the difficulties of modern science and cook books and books about the Loch Ness monster and travel books, mostly about East Grinstead….I write children’s books and school textbooks and works of abstruse philosophy…and scholarly articles on the Etruscans and works of sociology and anthropology. I write articles for the women’s page and send in stories about the most unforgettable characters I have ever met to Reader’s Digest….I write romantic novels under a female pseudonym and detective stories…I write traffic signs and “this side up” instructions for cardboard boxes. I believe I am really a writer.

Do you do any writing other than fiction? Have you tried morning pages? How do you exercise your cranial creative capacity?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Walt Whitman’s poem “Song of Myself” begins this way (spelling in original):

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.

Walt was on to something, namely, it is much better to observe grass than to smoke it. Loafing is not about psychoactive stimulation. It’s about inviting your soul.

Which is exactly what we should invite as writers. It is what makes our writing, our voice, unique. It is what a machine does not, and can never possess.

So just how do we invite our soul? We can practice creative loafing.

I had the privilege of knowing Dallas Willard, who was for many years a professor of philosophy at USC, where your humble scribe studied law. Willard was widely known for writing about the spiritual disciplines, e.g., prayer, fasting, simplicity, service, etc. I once asked him what he considered the most important discipline, and he immediately responded, “Solitude.”

That threw me at first. But the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. Solitude, which also includes silence, clears out the noise in our heads, the muck and mire, so we can truly listen.

“In silence,” Willard wrote, “we come to attend.”

Our world is not set up for solitude, silence, contemplation.

Boy howdy, how hard that is for us! According to a recent survey, Americans check their phones 205 times per day. Further:

Needless to say, this doesn’t “invite your soul.” Loafing, even boredom, does. As one neuroscientist puts it:

Boredom can actually foster creative ideas, refilling your dwindling reservoir, replenishing your work mojo and providing an incubation period for embryonic work ideas to hatch. In those moments that might seem boring, empty and needless, strategies and solutions that have been there all along in some embryonic form are given space and come to life. And your brain gets a much needed rest when we’re not working it too hard. Famous writers have said their most creative ideas come to them when they’re moving furniture, taking a shower, or pulling weeds. These eureka moments are called insight.

Learn how to loaf, I say! And it is a discipline. I take Sundays off from writing. It’s not easy. I feel myself wanting to write a “just a little” (which inevitably becomes “a lot”). I have to fight it. If I win the fight, I always feel refreshed and more creative on Monday.

Try this: Leave your phone in another room and sit alone in a chair for five minutes and don’t think about anything but your breath going in and out. You’ll be amazed how hard that is. But it’s a start. If you’re working on your WIP, take a few five-minute breaks to loaf and invite your soul. You’ll get better at it. And your work will get better, too.

I will finish with this moving story about silence.

A fellow enters a monastery and has to take a vow of silence. But once a year he can write one word on the chalkboard in front of the head monk.

The first year goes by and it’s really hard not to talk. Word Day comes around and the monk writes “The” on the chalkboard. The second year is really painful. When Word Day comes he scratches “food” on the chalkboard.

The third year is excruciating, the monk struggles through it, and when Word Day rolls around once more, he writes “stinks.” And the head monk looks at him and says, “What’s with you? You’ve been here for three years and all you’ve done is complain.”

How are you at creative loafing?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

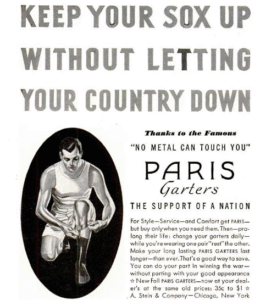

At the turn of the last century, the Second Industrial Revolution was well underway (dating roughly from the mid-19th to the mid-20th). Demographics moved from rural to urban. Cities swelled. And men faced a real problem—sagging socks.

At the turn of the last century, the Second Industrial Revolution was well underway (dating roughly from the mid-19th to the mid-20th). Demographics moved from rural to urban. Cities swelled. And men faced a real problem—sagging socks.

Oh, it was fine back on the farm, when only Bessie the cow and a few scattered chickens were witnesses to sartorial sag. But for the city-dwelling male—businessmen, newspaper reporters, plainclothes cops, or any man going to a public space like a ballgame, church, or saloon—slumping hose was a real challenge. Thus arose the men’s garter business. (It would not be until the late 1930s that synthetic fiber was patented by DuPont and made possible elastic socks.)

Novels can sag, too, in five key areas. Let’s see if we can’t make them tighter and firmer, and eliminate the need for garters.

We talk a lot about opening pages here, for obvious reasons. They can make or break a potential sale. (Search our archives for First Page Critiques.) I’ve written about beginning with a disturbance. This is an automatic hook. The enemy is too much backstory and exposition.

Sag Fix: Act first, explain later. Cut out all explanatory material on the first few pages. But I need the readers to know the circumstances and set up, don’t I? No! “Exposition delayed is not exposition denied.” Readers will wait a long time for exposition if they’re caught up in a disturbance.

The Doorway of No Return is when the Lead is forced into the “death stakes” of the novel. It’s the turning point into Act 2 and the main plot. In classic movie structure, this happens at the 1/4 mark. In a novel, I’ve found that it’s best at the 1/5 mark. But that’s too much to think about! I just want to write my story! I hate outlines!

I hear you, pantser. Keep your pants on. Write the way that makes you happy. But if you don’t know structure, all that happy creativity may be for naught. If a reader is going along and starts feeling This story is dragging, they may not stick around.

Sag Fix: Know how and where to cut or move scenes, so that the battle is joined around the 20% mark. You can look at the total word count of your first draft to figure it out. I use Scrivener with four folders: Act 1, Act 2a, Act 2b, and Act 3. Scrivener shows me the total word count in each folder.

There are times when you slow the action a bit to have the Lead confer with a friend or confidante or potential ally. Often these are “eating scenes,” which has its own fixes (see How to Write an Eating Scene).

Sag Fix: You can always find a way to insert tension into a friend scene. Something inside a character is making conversation difficult. For example, your Lead doesn’t want to fully open up about something, and the friend starts to probe. Brainstorm possibilities.

Oh boy, that sagging middle! It’s a three-bear problem: Is it too cold? Too hot? Just right? Is it too short? Too long? Too boring?

It’s funny (or nerve-wracking) how so many writers report the same problem around the 20k or 30k mark. “Holy Moly! Here I am and I’ve got 60k or more words to go! Yikes! Do I have enough going on? Too much? Is it getting out of hand? Or is this thing I’m writing just a novella? Should I make this a “trunk” novel and put it away for another time? Or should I just junk it? Is this wasted effort? Where did I put the bourbon?”

There are too many ways writers get lost in the Act 2 weeds that it is beyond one section of a blog post to deal with. (Let me modestly mention that I cover the whole subject in my book Plotman to the Rescue.)

Avoid the temptation to add “padding.” By that I mean scenes you conceive just to increase word count, as opposed to scenes that are organically related to the plot.

Sag Fixes:

When the final battle has been won (or in some cases, lost), and the loose ends all accounted for, wrap it up! Don’t give us pages and pages of after-plot.

Sag Fix: Add a scene that adds resonance to the ending. This is a scene that resolves a character issue for the Lead. It should be short and sweet, as it is in my favorite Bosch, Lost Light.

She lets go of her mother’s hand and extended hers to me. I took it and she wrapped her tiny fingers around my index finger. I shifted forward until my knees were on the floor and I was sitting back on my heels. She peeked her eyes out at me. She didn’t seem scared. Just cautious. I raised my other hand and she gave me her other hand, the fingers wrapping the same way around my one.

I leaned forward and raised her tiny fists and held them against my closed eyes. In that moment I knew all the mysteries were solved. That I was home. That I was saved.

This fulfills Spillane’s axiom that “the last chapter sells your next book.” Connelly has sold quite a few. Go thou and do likewise.

What plot sags have you encountered? What do you do about them?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Colin Clive in Frankenstein

In the classic Universal horror movie Frankenstein, Colin Clive, overacting as Dr. Frankenstein, shouts, “IT’S ALIVE! IT’S ALIIIIIIVE!” He’s thrilled to the core when his creation takes on real life.

The doc was onto something. Isn’t that how you feel when your character starts to come alive as you write?

While there are many aspects of great character work, I think the following three features are always present.

Compelling characters have a way of looking at the world that is uniquely their own. This is attitude, and done well it sets them apart from every other fictional creation.

If you are writing in first-person point of view, attitude should permeate the voice of the narrator. Julianna Baggott’s Lead in Girl Talk, Lissy Jablonski, is smart, witty and a bit cynical. She describes an old boyfriend:

He’d been a ceramics major because he wanted to get dirty, a philosophy major because he wanted to be allowed to think dirty, a forestry major because he wanted to be one with the dirt, and a psychology major because he wanted to help people deal with their dirt. But nothing suited him.

We learn a lot about Lissy from her singular voice. One thing she’s not is dull.

A third-person character shows attitude primarily through dialogue and thoughts. In L.A. Justice we’re given a look into the head of Nikki Hill, the deputy D.A. who is the Lead in the Christopher Darden/Dick Lochte legal thriller. In one scene she reacts to her superior, the acting D.A. He’s a man of two personalities she had labeled “Dr. Jazz” and “Mr. Snide.” In the office he was the latter, bent and dour, with an acid tongue and total lack of social grace . . . At the moment, he was definitely in his Mr. Snide mode.

This is a quick look at Nikki’s attitude toward authority, which continues to be developed in the novel.

The best way to find your character’s unique views is to listen. You do this by creating a free-form journal in the character’s voice. It’s okay if you don’t know what the voice is going to sound like when you start. Keep writing, fast and furious, in ten to twenty minute stretches. A voice will begin to emerge.

Have the character to pontificate on such questions as:

Let the answers come in any form, without editing. Your goal is not to create usable copy (though you certainly will find some gems). Rather, you want to get to know, deeply, the character with whom you’re going to spend an entire novel.

A great novel, I say again, is the record of how a character overcomes some form of death—physical, professional, or psychological. Which means the Lead has to have guts.

In Rose Madder, Stephen King gives us a Lead who is weak and vulnerable—a terribly abused wife. In the Prologue we see Rose Daniels, pregnant, savagely beaten by her husband. The section ends, Rose McClendon Daniels slept within her husband’s madness for nine more years.

Chapter One begins with Rose, bleeding from the nose, finally listening to the voice inside her that says leave. She argues with herself. Her husband will kill her if she tries. Where will she go? But finally she works up the courage to open the front door and take her first dozen steps into the fogbank which was her future.

Every step she takes now requires courage. Rose is unprepared for dealing with the outside world, with simple things like getting a bus ticket or a job. And all the while she knows her husband is going to be tracking her. Still, she moves forward, and we root for her.

3. Surprises

A character who never surprises us is dull by definition.

Surprising behavior often surfaces under conditions of excitement, stress or inner conflict. Archie Caswell, the 14-year-old protagonist of Han Nolan’s When We Were Saints, is torn about his experience of the divine. Alone on a mountain he dug his hands into the ground beneath him, pulling up pine needles and dirt. He threw it at the trees. He picked up some more and threw it, too. He berates God, then asks God’s forgiveness.

It’s completely unexpected behavior from a heretofore normal, troublemaking kid. And bonds us to him all the more.

When your character has an emotional reaction, don’t choose the first one that comes to mind. That’ll be expected. Brainstorm. Make a surprise.

If you plumb the depths of your characters’ lives by exploring these three aspects, your fiction will truly come ALIIIIIIVE!

What do you do to bring life to your characters?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Or should that be Wither Social Media?

Or should that be Wither Social Media?

A couple of months ago I wrote about the scourge of phishing, bot-generated emails sent to writers with books on Amazon, purporting to be from marketing gurus who can get your book “the attention it deserves” or some such. Generated from a cubicle in some foreign land, what they want is your money and access to your KDP (and even bank) account. The bot-letter starts with a dopamine hit on how great your book is, adding some details scraped from the internet to make it sound like they’ve actually given your book a careful reading. (Hint: no live, human marketing professional finds random books and gives them a careful reading, then crafts a client-seeking email.)

I and many authors I know get these daily. But there’s been a new development. Skynet AI keeps training itself, and knows that authors have warned their fellows about this scam. So I had a good laugh other day when I got one of these that eschewed a fake professional style and generated a cutesy, I’m-cool-and-fun-and-down-with-the-kids type voice. What really got me chortling was this paragraph:

Before you picture me as another one of those “promo bots” crawling out of the algorithm swamp, relax. I’m Alisa, and I run a community of book-hungry readers who devour stories like yours and actually leave honest, detailed reviews (yes, human ones, no Mars-based bots or shady smoke-filled deals involved).

Got that? A bot assuring me it’s not a bot! Which got me thinking about just how we’re going to be able to judge what’s real and what’s not in the years ahead.

Now we have “AI social media.” Whatever that means, it probably means “kissing reality goodbye.”

OpenAI released the Sora app on Tuesday, just days after Meta released a similar product as part of its Meta AI platform. NPR took an early look and found that OpenAI’s app could easily generate very realistic videos, including of real individuals (with their permission). The early results are both wowing and worrying researchers.

“You can create insanely real looking videos, with your friends saying things that they would never say,” said Solomon Messing, an associate professor at New York University in the Center for Social Media and Politics. “I think we might be in the era where seeing is not believing.”

More:

“We’re really seeing the ability to kind of whole-cloth generate incredibly realistic, hyper-realistic content in any kind of different way you want,” said Henry Ajder, the head of Latent-Space Advisory, which tracks the evolution of AI-generated content.

As concerned as he is with people being duped, Ajder said he’s also very concerned about the consequences of nobody trusting what they see online.

“We have to resist the somewhat nihilistic pull of, ‘we can’t tell what’s real anymore, and therefore it doesn’t matter anymore,'” he said.

The astute publishing expert Thomas Umstaddt, Jr. was recently a guest on the Writing Off Social podcast talking about social media.

Thomas: The metaphor I like to use is that social media is like a sporting event. The people in the stands are shouting as loud as they can, but just because you are shouting louder than everyone else doesn’t make you famous on social media.

Social media only works for the people on the field. If you’re the quarterback, for instance, social media works for you. The same goes for major brands like Coca-Cola that advertise in the stadium. But regular fans in the crowd can’t get famous on social media. It’s an illusion. Buying a ticket doesn’t make the crowd listen to you.

That’s how social media works for most authors. You can’t expect to shout about your book amongst all the other shouting and get people to listen.

Sandy: It’s an illusion of access. You think you have access to all 5.24 billion people who are on social media.

Thomas: Many of those are AI bots.

Sandy: True. Regardless, you go there and think you have access to billions of people, when in reality, you only have access to a handful. The people who see your content are the ones immediately around you who can actually hear you. That’s it.

So what are we as authors to do with social media? The early counsel was to jump in with both feet (or both hands on the keyboard, as it were), on as many platforms as you can, because of the “reach billions” hype. Ha! No. We are in the stands at a Seattle Seahawks game, and the people in the adjoining seats can barely hear us when we scream.

Does social media make any difference (meaning, does it sell books?) TikTok is the latest rage, but there’s a tsunami of content there and getting through that noise is even worse than in a packed stadium. (I once threatened my daughter by telling her I was going to start doing “dad-dancing” videos on TikTok. She said, in all seriousness, “That can work. You could really go viral, Pop.”)

Um, no.

Social media has never been a place to sell books. If you have the right book, the right market, and the right reach, maybe you can move a few copies. But the truth remains: unless the book itself is so good that the last chapter sells your next book, you’ve spun a lot of wheels and invested a lot of time for little return.

My advice early on was to pick one social media platform you enjoy, and major in that, but not with a string of “buy my book” posts. I subscribe to the 90/10 rule, with the 90 being welcome, non-commercial content, and the 10 about your books. Make 100 percent of it fun to read. Don’t become yet another scold about some political or cultural hobbyhorse. It’s not good for the ol’ psyche.

FWIW, my social media footprint has been X (formerly Twitter), but I’m most active now on my Substack, which is a blend of newsletter and mini-social community (i.e., comments). It is there that I post another kind of writing I call “Whimsical Wanderings” as an oasis from the screaming mimi-dom of most social media today.

But I always keep writing books the main thing.

What about you? What’s your view of social media for authors? How much time do you spend on it? Any advice you’d like to offer?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Last week we began a discussion of Frank Capra’s 1934 classic It Happened One Night. It was spurred by my meeting with a couple of young ladies at Trader Joe’s who do not watch black-and-white movies. Matters took an alarming turn in the comments when Brother Gilstrap told of a 22-year old fellow in media who’d never heard of Clark Gable or John Wayne!

Last week we began a discussion of Frank Capra’s 1934 classic It Happened One Night. It was spurred by my meeting with a couple of young ladies at Trader Joe’s who do not watch black-and-white movies. Matters took an alarming turn in the comments when Brother Gilstrap told of a 22-year old fellow in media who’d never heard of Clark Gable or John Wayne!

This almost drove me to drink. Instead, with hope in my heart and zeal in my fingers, I clack on.

The plot of It Happened One Night (which Capra and screenwriter Robert Riskin refined after priceless feedback from a writer named Myles Connolly) is simple. Spoiled heiress Ellie Andrews (Claudette Colbert) wants to get to her husband in New York, flier King Westley. But she is held a virtual prisoner on her father’s yacht so he can pay off Westley to have the marriage annulled. She dives overboard and swims to freedom. Wishing to stay incognito she gets on a night bus, but is woefully deficient in street smarts. Another passenger, a fired newspaper reporter named Peter Warne (Clark Gable), spots her and offers her help her get to Westley in exchange for her story, exclusive. She resists until she realizes that only he can keep her on the down low. And so the journey begins.

Death Stakes

As I’ve written many times, the best fiction is about a battle with death, which comes in three forms: physical, professional/vocational, or psychological/spiritual.

For Ellie, it’s psychological death, as it usually is in a romance. The standard trope is that unless they two “soul mates” end up together, they’ll “die on the inside.” Here, there’s a twist: Eillie wants to get to Westley mainly to rebel against her controlling father. She’ll “die inside” if she isn’t allowed to live her own life.

For Peter, it’s professional death. His editor at a New York newspaper has told him never to show his face there again. Peter needs a story, a scoop, or his reporting days are over.

Lesson: Nail your death stakes from the jump, or your plot will have a weak foundation. You can have more than one on the line, though one should be primary. For example, a thriller will almost always have physical death as the crux, but the character can also have psychological challenge as well.

A Romance of Opposites

Who are these two at the start of the picture? Ellie is a spoiled brat. Thus, one part of the plot is The Taming of the Shrew. But the brilliant move by Capra/Riskin is that Peter is an egotist who also needs taming. It’s a perfect balance.

Who are these two at the start of the picture? Ellie is a spoiled brat. Thus, one part of the plot is The Taming of the Shrew. But the brilliant move by Capra/Riskin is that Peter is an egotist who also needs taming. It’s a perfect balance.

There are two main romance tropes: 1. The couple who hate each other at first, then grow into love; and, 2. The lovers who want to be together but are kept apart by other forces, e.g. Romeo and Juliet. This movie is obviously the first kind.

Lesson: Know your tropes because the readers expect them. Disappointed readers do not become return buyers. Your task is to originalize how tropes are played out. This movie does that exquisitely.

Three Unforgettable Scenes and No Weak Ones

Writer-director John Huston once said that a great movie must have at least three unforgettable scenes, and no weak ones. Here are the three I’d pick in It Happened One Night.

1. Early in Act 2 Peter, to conserve their money, rents a single cabin at an auto camp, registering as husband and wife. Ellie is aghast. Peter ties a rope across the room between the two beds and throws a blanket over it. “Behold the walls of Jericho,” he says. “Maybe not as thick as the ones that Joshua blew down with his trumpet. But a lot safer. You see, I have no trumpet….Do you mind joining the Israelites?”

Ellie just stands there, defiant. So Peter decides to show her how a man undresses. It’s “quite a study in psychology.” He takes off his coat, his tie, then his shirt. He’s about to remove his pants when Ellie quickly scoots to the other side.

What made this unforgettable was not only Gable’s delivery of the lines, but the fact that he wore no undershirt. After this movie came out, undershirt sales in America suffered a serious decline!

2. The most famous scene in the movie is the hitchhiking scene. Peter has been bragging to Ellie how he knows everything, including the right way to dunk a donut. “I ought to write a book about it.” On the road, he explains to Ellie he can get a ride by the magic of this thumb and explains the various thumb moves. He says he’s going to write a book about it called “The Hitchhiker’s Hail.” Ellie is not impressed.

As cars stream by, Peter tries every one of the moves and not a single car stops. Crestfallen, he says, “I don’t think I’ll write that book after all.”

Ellie says, “You mind if I try?”

“You? Don’t make me laugh.”

“I’ll stop a car and I won’t use my thumb…It’s a system all my own.”

Ellie then waits for the next car. When it comes she raises her skirt and sticks out her attractive gam. The car screeches to a halt. The taming of the egotist has begun.

3. The wedding scene at the end, when Ellie is about to marry King Westley once more and makes an unforgettable escape.

Lesson: However you plan your scenes, be ye outliner (before) or pantser (during) push yourself to the original, the fresh, the unanticipated.

Spicy Minor Characters

I call minor characters the “spice” of great fiction (see Mr. Charles Dickens for the Master Class). Two of them come by way of two of the best character actors of the time, Roscoe Karns and Alan Hale.

Karns plays Oscar Shapeley, an oily (and married) traveling salesman who fancies himself a ladies’ man. On the night bus he starts yakking to Ellie. “Shapeley’s the name and that’s the way I like ’em.” On and on he goes, until Ellie cuts him down with a line.

Karns plays Oscar Shapeley, an oily (and married) traveling salesman who fancies himself a ladies’ man. On the night bus he starts yakking to Ellie. “Shapeley’s the name and that’s the way I like ’em.” On and on he goes, until Ellie cuts him down with a line.

“Hoo hoo!” says Shapeley. “There’s nothing I like better than to meet a high-class mama that can snap ’em back at you, ’cause the colder they are, the hotter they get. Yessir, that’s what I always say. When a cold mama gets hot, boy how she sizzles. Now you’re just my type. Believe me, sister, I could go for you in a big way. Fun-on-the-side Shapeley they call me, with accent on the fun. Believe you me!”

Peter has been watching all this with amusement, but finally saves Ellie by telling Shapeley to move to another seat because “I’d like to sit next to my wife.” Shapeley quickly complies.

Later, Shapeley will show up again, after figuring out who Ellie really is. Peter will then scare the pants off Shapeley by pretending to be a mobster who is “holding that dame for a million smackers.” And if Shapeley talks, the mob will find him and his family. Scared to death, Shapeley runs off into the woods.

In the hitchhiking scene, the car that stops is driven by Alan Hale (you may remember him as Little John in The Adventures of Robin Hood). He is loud, jovial, talkative.

In the hitchhiking scene, the car that stops is driven by Alan Hale (you may remember him as Little John in The Adventures of Robin Hood). He is loud, jovial, talkative.

“So, you’re just married? That’s pretty good. But if I was young, that’s the way I’d spend my honeymoon. Hitchhiking. Yes, sir.” He begins to sing: “Hitchhiking down the highway of love on a honeymoon!”

It turns out he’s a “road thief” who picks people up then drives off with their luggage. It’s a short bit, but a flavorful spice.

Lesson: Do not waste your minor characters by making them clichéd or throwaways. Give them a life of their own, with unique tags of manner and speech. Readers love spice. It’s one of the best ways to elevate your work above “AI slop.”

Dialogue

I’ve long held that the fastest way to improve any manuscript is with sharp, orchestrated dialogue. The movie is full of smart Riskin banter. One example: When Peter first sits next to Ellie on the bus, she is not pleased. He offers to put her bag up top for her. She gets up to do it herself. The bus lurches forward and she falls back on Peter’s lap. She quickly scoots off. Peter grins. “Next time you drop in, bring your folks.”

Lesson: Standout dialogue is a craft that can be learned. I ought to write a book about it.

Pet the Dog

A “pet the dog” beat is a moment in Act 2 when the lead helps someone who needs it, even though it comes with a cost. In the movie, the passengers on the night bus are bonding by singing “The Man on the Flying Trapeze” (a popular ditty of the day). Then the bus hits a muddy rut and comes to a hard stop, tossing the passengers. They mostly laugh, but suddenly a little boy is screaming “Ma! What’s the matter with you? Somebody help!” Peter rushes over, determines the mother has passed out and assures the boy she’ll come around.

“We ain’t ate nothin’ since yesterday,” the boy says. He says his mother has a job waiting for her in New York but had to spend all their money on the tickets. Peter reaches into his pocket for a bill, a ten-spot he and Ellie need for the trip. He hesitates. Ellie takes the bill, hands it to the boy and tells him to buy something to eat at the next stop. The boy says he “shouldn’t oughta” take it. He holds the bill out to Peter, “You might need it.” Peter waves him off and puts on a smile. “I got millions.”

Lesson: Pet the dog moments deepen our bond to characters. Think of Katniss with little Rue, or Richard Kimble getting the distressed boy to the operating room in The Fugitive. The key is that the act puts the character in a worse position in the plot.

Final Thoughts

Capra always said that the Gable in It Happened One Night was the real Gable—unabashedly masculine, with a vein of sardonic humor. Colbert showed herself adept at drama, comedy, and pathos, playing a “brat” whose inner decency finally breaks out. In true rom-com fashion, each transforms the other for their ultimate good.

Would that today we had more movies as tight and multi-faceted as It Happened One Night.

And books, too.

Black-and-white movies forever!

Comments Welcome.

Note: It Happened One Night is free to watch on YouTube.

And for your viewing pleasure, here’s the famous hitchhiking scene:

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

The sun was shining, the sky was blue (sorry, Elmore, for starting with the weather). So I decided to take a walk to Trader Joe’s. At checkout the pleasant young lady asked, “How’s your day going?”

The sun was shining, the sky was blue (sorry, Elmore, for starting with the weather). So I decided to take a walk to Trader Joe’s. At checkout the pleasant young lady asked, “How’s your day going?”

“Swell,” I said. “It’s such a nice day, I walked here.”

“You walked?”

“Only half a mile.”

“Nice. Any plans for the rest of your day?”

“I’m going to watch an old movie.”

“Oh, which one?”

“The Women.”

“I haven’t heard of that one.”

“1939. Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Roz Russell.”

She frowned. “Is it in black and white?”

“It is indeed.”

She pursed her lips.

I said, “Don’t you watch black and white movies?”

“Not really,” she said.

“Oh boy!” says I. “There are so many great movies waiting for you to see! You can start with Casablanca.”

“I’ve heard of that. I’ll have to check it out.”

Another pleasant young lady appeared to bag my items. “Check what out?” she said.

“An old movie,” the checker said.

“Casablanca,” I said.

“Oh, yeah,” said the bagger.

“You’ve seen it?”

She shook her head. “But I’ve heard about it.”

“You both need to see Casablanca.”

“I will,” said the checker with a smile. The bagger nodded.

“My work here is done,” I said.

It is my work indeed to extol the virtues of classic movies for entertainment, edification, and writing instruction. When I started teaching over 25 years ago and would mention Casablanca, everybody had seen it. Not these days. When I speak to young writers now, most of them have not seen it. Which blows my mind!

Yes, Virginia, there are black and white movies you must see if you wish to write (and now I wonder how many youngsters know where Yes, Virginia comes from. But I wonder a great many things these days).

Today I want to talk about another pure classic every writer, especially romance writers, should know—Frank Capra’s 1934 mega-hit It Happened One Night. Arguably the first true rom-com, the movie swept the major Oscars: Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, Screenplay.

Today I want to talk about another pure classic every writer, especially romance writers, should know—Frank Capra’s 1934 mega-hit It Happened One Night. Arguably the first true rom-com, the movie swept the major Oscars: Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, Screenplay.

And it almost didn’t get made.

Capra tells the story in his autobiography, The Name Above the Title. The short version is that no one but Capra and his screenwriter, Robert Riskin, wanted to make the movie, originally titled Night Bus. Capra had to fight the mercurial Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures to get it done. And potential stars kept turning it down.

MGM owed Cohn one of their stars for a picture, because of a previous deal. For Night Bus, Louis B. Mayer sent him Clark Gable, partly to “punish” Gable for being difficult over salary. It was “punishment” because Columbia was considered far below MGM in prestige. Which is why Gable showed up to his first meeting with Capra three sheets to the wind. He had no idea this was going to be life changing for him.

Finding the lead actress was more difficult. After several turn downs, Capra went to his last resort. He had worked with Claudette Colbert before, but the movie turned out to be a stinker. She wasn’t wild about working with Capra again, but said she’d do it if she got double her usual salary and the shooting would be finished in four weeks so as not to interrupt a planned vacation. She thought that would be a deal breaker. But Capra accepted. A shooting date was set.

But there was another problem, the script itself. Capra and Riskin had laughed a lot as they wrote the first draft of Night Bus. But their enthusiasm wasn’t shared by anyone else. It had some funny bits, but they were too close to the material to see the gaping hole.

Which is when Capra showed it to a “beta reader,” his friend Myles Connolly.

The Golden Advice That Made a Hit

Myles Connolly was a “hard-boiled newspaper reporter” turned Hollywood scribe. He was especially adept at seeing what was wrong in other scripts. He told Capra:

Frank, it’s easy to see why performers turn down your script. Sure, you’ve got some good comedy routines, but your leading characters are non-sympathetic, non-interest grabbing. People can’t identify with them. Take your girl. A spoiled brat, a rich heiress. How many spoiled heiresses do people know? And how many give a damn what happens to them? She’s a zero. Take your leading man. A long-haired, flowing-tie, Greenwich Village painter. I don’t know any vagabond painters and I doubt if you do. And a man I don’t know is a man I’m apt to dislike, especially if he has no ideals, no dragons to slay. Another zero. And when zero meets zero you’ve got zero interest.

He went on to suggest making the heiress want something to make her more sympathetic, like getting away from her controlling father. And make the man a tough, crusading reporter on the outs with his pig-headed editor and needing a story. Boom! Capra and Riskin knew he was right, and set about re-writing the script.

Retitled It Happened One Night, Capra shot the movie in the allotted four weeks. And the rest, as they say, is movie history. Next week I’ll unpack it.

For now, two takeaways. First, for your lead character, you must create an immediate rooting interest, something that hooks the reader and gets them on the character’s side, even if the character is flawed at the beginning. An opening objective. Scarlett is a brat, but she’s also in love with Ashley. [Tip: We always root for people in love, at least for a while.] So we’ll follow her along for a time to see if she gets him. We’ll also see that she has an inner strength [Tip: We always root for people fighting long odds] and hope that moxie might turn Scarlett into a better version of herself.

Tip: Ask, What does my character yearn for before the story begins?

The other takeaway is the value of a trusted editor or beta reader. I’ve been lucky over the years to work with some fantastic editors who made me a better writer, and with some priceless beta readers (starting with Mrs. B) who always see things I don’t. This is not a profession that rewards pride or narcissism, so don’t park your keister in either place.

Myles Connolly saved Night Bus from bombing. Had it done so, we might never have had all the great Capra movies to follow, or the roles where a “new” Gable really strutted his stuff—from San Francisco to Gone With the Wind, all the way to Teacher’s Pet.

1. Do you consider your lead character’s yearning before the story begins?

2. Do you have a trusted editor or beta reader(s)? How have they helped you? What advice can you give to a writer who wants to find a good one?