by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

It’s been 18 years already! Can you believe it? The Kindle came out in late 2007. So did a little device I like to call the iPhone. These twin explosions (to put it mildly) changed the world of publishing and reading—and even the culture—forever (I mean, in 2006 you never saw a mom or dad pushing a stroller in broad daylight with their face glued to a phone, as little junior or missy plays with a tablet with digital bunnies instead of looking at live birds flying in the sky).

It’s been 18 years already! Can you believe it? The Kindle came out in late 2007. So did a little device I like to call the iPhone. These twin explosions (to put it mildly) changed the world of publishing and reading—and even the culture—forever (I mean, in 2006 you never saw a mom or dad pushing a stroller in broad daylight with their face glued to a phone, as little junior or missy plays with a tablet with digital bunnies instead of looking at live birds flying in the sky).

In 2007 we had two major tragedies: The Sopranos ended and Keeping Up With the Kardashians began.

Evel Knievel, age 69, died in 2007 (shockingly, of natural causes). Tony Bennett, age 80, got married (but did he leave his heart in San Francisco? I certainly hope not).

Where were you in 2007? I was on the verge of signing a new contract with a major publishing house. Traditional publishing was my home. Back then all writers longed to make it through the gates of the Forbidden City.

Then in 2008 and ’09, seemingly out of nowhere, brand-spanking new writers publishing 99¢ Kindle books directly on Amazon started raking in huge bucks. The indie revolution had begun.

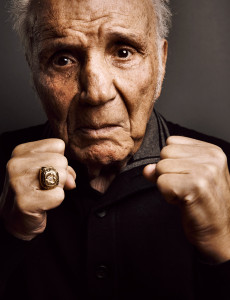

It exploded over the next several years, along with prophecies of the demise of traditional publishing. At the time I noted that reports of trad’s death were greatly exaggerated, likening the biz to Jake “Raging Bull” LaMotta who was famous for getting bloodied but never going down.

And so today we have the two paths—trad and indie—firmly established, each with its own set of challenges. I have been a happy indie since 2012. It’s a joy to publish a book the moment I deem it ready. So I wonder what advice I’d give today to an author yearning for a traditional publishing contract. Let me give it a whirl.

- You’re going to need lots of patience. And by that I mean, lots.

Over at the Books & Such Literary Agency blog, Rachel Kent explains a typical timeline in trad publishing:

- Revamping the proposal with your agent for submission to editors: 1–4 months

- Agent pitching and selling the project: 2 months–2 years (sometimes longer and there’s no guarantee of a sale)

- Contract negotiation: 2 weeks–4 months

- Final book is due: 0–18 months after contract

- Editorial revision letter back to author: Approximately 2 months after book is turned in.

- Revisions done by author and sent back to publishing house: 7-30 days from the time the revision letter is received.

- Galleys to author: 4–6 months after revisions

- Galley corrections back to publisher: 7–14 days after receipt of galleys.

- Book goes to the printer: 1–14 days after galleys are finalized.

- Book ships to stores: 1–2 months after it is sent to printer.

- Book officially releases: 1–2 weeks after stores receive the product.

Note that chilling number: It can take up to 2 years for an agent to pitch a project with no guarantee of a sale. And if the book is published, there is no guarantee that it will sell in sufficient numbers to get another contract.

If it’s still your dream to be traditionally published, that’s fine. Everyone should pursue their dreams. Just be aware of the above, and:

- Don’t expect the system to change for you

It’s a glacially slow and frustrating process. It is what it is. I wish it was what it could be. So does writer and former agent Nathan Bransford. He recently offered a “Publishing Submission Bill of Rights” for the publishing industry which I like very much, including:

Article 1 – If you are a publishing professional who’s open for submissions, you owe everyone who follows your submission guidelines a timely response…

Article 2 – If you are an author or agent who doesn’t follow submission guidelines, you are not entitled to a response…

Article 3 – One month for queries and two months for manuscripts is an acceptable timeline unless otherwise agreed – If you’re a publishing professional who can’t stay on top of incoming submissions you should close for submissions, get more assistance, or request fewer manuscripts. Again, it’s unfair to authors to leave them in limbo with hazy timelines…

Article 4 – “Thanks but not for me” is not only an acceptable submission response, it’s better than saying something just to say something – The submission system should reward timeliness and clarity over detailed feedback…

Article 5 – If you receive “thanks but not for me,” you are not owed further clarification. Don’t ask. Don’t bog down the process or put undue pressure on agents and editors who simply say “not for me.” If they only have a gut feeling and don’t have anything helpful to add, don’t follow-up. Just move on.

All that said, the primary advice I’d give to a young writer seeking trad publishing is keep the main thing the main thing. The best book you can write is the main thing. And don’t be a snoot about learning the craft. Learn what works, and why, before you go off and “break the rules.” And don’t think AI is going to give you any shortcuts. If you rely on it for the writing itself, it will give you a competent product at the same time it melts your brain. And competent fiction does not make fans. Unforgettable fiction does, and for that you must tap your heart and your blood, and know how to translate them through craft.

Further advice:

- No agent is better than a bad agent. Do your due diligence.

- Educate yourself on publishing contracts, esp. the non-compete clause and the reversion of rights clause (tie the latter to royalties, not “out of print”).

- Don’t hang your ultimate happiness on getting published. If you don’t make it, you’ll be severely disappointed. If you do make it, your books may not sell enough to keep you inside the Forbidden City. And if you do make it to the “A List” and think you’ll be eternally and gloriously happy, read the end of The Great Gatsby again.

- Manage expectations, write and learn, and find your joy in the production of good words.

Carpe Typem.

Seize the Keyboard.

Over to you now. What’s your view of traditional publishing these days? Any further advice you’d give our hypothetical writer?