Sometimes I come across posts on writing blogs that I feel compelled to share with everyone at TKZ. One such informative post deals with what happens once you finish your first draft. With permission from its author, the great writer and teacher, Joanna Penn, here is a repost of her advice on the subject. Enjoy. – Joe Moore

——————————-

Many new writers are confused about what happens after you have managed to get the first draft out of your head and onto the page.

I joined NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) this year and ended up with 27,774 words on a crime novel, the first in a new series. It’s not an entire first draft but it’s a step in the right direction and the plotting time was sorely needed.

I joined NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) this year and ended up with 27,774 words on a crime novel, the first in a new series. It’s not an entire first draft but it’s a step in the right direction and the plotting time was sorely needed.

Maybe you ‘won’ NaNo or maybe you have the first draft of another book in your drawer, but we all need to take the next step in the process in order to end up with a finished product.

Here’s my process, and I believe it’s relevant whether you are writing fiction or non-fiction.

(1) Rewriting and redrafting. Repeat until satisfied.

For many writers, the first draft is just the bare bones of the finished work and often no one will ever see that version of the manuscript. Remember the wise words of Anne Lamott in ‘Bird by Bird‘ “Write shitty first drafts.” You can’t edit a blank page but once those words are down, you can improve on them. [More books for writers here.]

I love the rewriting and redrafting process. Once I have a first draft I print the whole thing out and do the first pass with handwritten notes. I write all kinds of notes in the margins and scribble and cross things out. I note down new scenes that need writing, continuity issues, problems with characters and much more. That first pass usually takes a while. Then I go back and start a major rewrite based on those notes.

After that’s done, I will print again and repeat the process, but that usually results in fewer changes. Then I edit on the Kindle for word choice. I add all the changes back into Scrivener which is my #1 writing and publishing tool.

(2) Structural edit/ Editorial review

I absolutely recommend a structural edit if this is your first book, or the first book in a series. A structural edit is usually given to you as a separate document, broken down into sections based on what is being evaluated. You can find a list of editors here.

I had a structural edit for Stone of Fire (previously Pentecost) in 2010 and reported back on that experience here. As the other ARKANE novels follow a similar formula, I didn’t get structural edits for Crypt of Bone and Ark of Blood. However, I will be getting one for the new crime novel when it is ready because it is a different type of book for me.

Here’s how to vet an independent editor if you are considering one.

(3) Revisions

When you get a structural edit back, there are usually lots of revisions to do, possibly even a complete rewrite. This may take a while …

(4) Beta readers

Beta readers are a trusted group of people who evaluate your book from a reader’s perspective. You should only give them the book if you are happy with it yourself because otherwise it is disrespectful of their time.

This could be a critique group, although I prefer a hand-picked group of 5 or 6 who bring different perspectives. I definitely have a couple of people who love the genre I am writing in as they will spot issues within the boundaries of what is expected, and then some people who consider other things.

My main rule with beta readers is to make changes if more than one person says the same thing. Click here for more on beta readers.

(5) Line edits

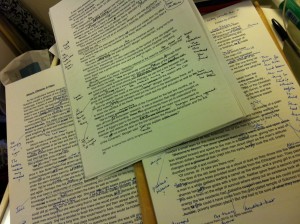

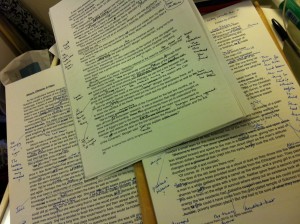

Line editor’s notes for Exodus

Line editor’s notes for Exodus

The result of line editing is the classic manuscript covered in red ink as an editor slashes your work to pieces!

You can get one of these edits before or after the beta readers, or even at the same time. I prefer afterwards as I make broader changes of the book based on their opinions so I want the line editor to get the almost final version.

Line edits are more about word choice, grammar and sentence structure. There may also be comments about the narrative itself but this is a more a comment on the reading experience by someone who is skilled at being critical around words.

The first time you get such a line edit, it hurts. You think you’re a writer and then someone changes practically every sentence. Ouch.

But editing makes your book stronger, and the reader will thank you for it. [You can find a list of editors here.]

(6) Revisions

You’ll need to make more changes based on the feedback of the beta readers and line editor. This can sometimes feel like a complete rewrite and takes a lot of detailed time as you have to check every sentence.

I usually make around 75% of the changes suggested by the line editor, as they are usually sensible, even though I am resistant at first. It is important to remember that you don’t have to change what they ask for though, so evaluate each suggestion but with a critical eye.

(7) Proof-reading

By this point, you cannot even see any mistakes you might have made. Inevitably, your corrections for line editing have exposed more issues, albeit minor ones.

So before I publish now, I get a final read-through from a proof-reader. (Thanks Liz atLibroEditing!) After Crypt of Bone was published, I even got an email from a reader saying congratulations because they had failed to find a single typo. Some readers really do care, for which I am grateful and that extra investment at the end can definitely pay off in terms of polishing the final product.

(8) Publication

Once I have corrected anything minor the proof-reading has brought to light, I will Compile the various file formats on Scrivener for the ebook publishing platforms. I will then back the files up a number of times, as I have done throughout the whole process.

(9) Post-publication

This may be anathema to some, but the beauty of ebook publishing is that you can update your files later. If someone finds a typo, no problem. If you want to update the back matter with your author website and mailing list details, no worries. If you want to rewrite the whole book, you can do that too (although some sites have stricter rules than Amazon around what is considered a new version.)

Budget: Time and money

Budget: Time and money

Every writer is different, and there are no rules.

But in terms of time, your revision process will likely take at least as long as the first draft and probably longer (unless you’re Lee Child who just writes one draft!). For my latest book, Exodus, the first draft took about 3 months and the rewriting process took about 6 months.

In terms of money, I would budget between $500 – $2000 depending on what level of editing you’re looking for, and how many rounds. You can find some editors I have interviewed as well as their prices here.

I believe editing at all these different stages is important, because it is our responsibility to make sure our books are the best they can be. But if you can’t afford professional editing, then consider using a critique group locally or online. The more eyes on the book before it goes out into the world, the better.

What’s your editing process? Do you have a similar approach or something completely different?

Joanna Penn is a New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of thrillers (as J.F.Penn) and non-fiction, a professional speaker and award-winning entrepreneur. Her site, TheCreativePenn is regularly voted one of the Top 10 sites for writers. Connect with Joanna on Twitter @thecreativepenn

![]() The Kill Zone blog makes its debut on 08/08/08. We’re an exciting group of thriller and mystery authors. Stay tuned!

The Kill Zone blog makes its debut on 08/08/08. We’re an exciting group of thriller and mystery authors. Stay tuned!