By PJ Parrish

I got into this novel racket back in 1979 as a writer of mainstream women’s fiction. (That was the euphemism of the era for big fat books about sex, power and dysfunctional families.) I retired from fulltime novel writing a couple years ago. (I had a great run and was time…no regrets). So over a span of oh, 40 years, I’ve had a lot of editors.

The good, the bad, and the ugly. And one, painfully indifferent. (We showed up at a major book fair and she didn’t know who we were).

I forgot who told me this early in my career — might have been one of my agents — but she said, “Your editor is not your friend.” And that is true. Now, some writers are lucky to have deep and long-lasting friendships with their editors. But I never expected that. All I wanted was an editor who made my books better, an editor who made me better. An editor who believed in my work.

First, a definition. There are copy editors. Then there are line editors, Both are essential to your success.

I’ve had some amazing copy editors — the pickiest, sharpest-eyed, obsessive, anal-grammarians an author could ever wish for. They caught my misspellings, my lay-lie transgressions, my syntax sins. My last one, at Thomas & Mercer, was an ex ballet dancer who caught some errors that even this old dance critic missed.

My favorite copy editor was one I had for my British edition romance. I never knew his/her name but I pictured her as a spinster sitting in a ratty wingback by the fire in some Devonshire outpost surrounded by cats and towers of manuscripts. She dripped blood-red pencil all over my pages. At one point, she scribbled in the margins next to my French phrases: “I don’t believe, based on the English errors uncovered thus far in this novel, that we should trust the author’s ability to write in another language.” She also took me to task for my “crutches” — “This author has an unfortunate propensity to use “stare” and “padded” (e.g. he padded toward the door). Would suggest striking every reference.”

I hated that woman. I loved that woman.

Every author has horror stories about bad editing. I had a copy editor who changed the color of key lime pie to green. Being in Manhattan, I guess she never saw a key lime — which is yellow. I was the one who had to answer the boy-are-you-dumb emails from fellow Floridians. And then there is the infamous Patricia Cornwell gaffe — the cover flap that talked about a grizzly murder — which set off a whole new sub-genre, serial killer bears.

When you spend eight months to a year writing a book, you get so close to it sometimes you can’t see the forest through the faux pas. You’re so intent on plot and character, you forget you’ve changed a character’s name halfway through. Or that it’s MackiNAW City but MackiNAC Island. Or that loons don’t stick around Michigan in winter…they migrate. One year I got so paranoid I hired a free lance copy editor. She caught so many mistakes it made me even more paranoid about what still lay (lie? lain?) beneath.

Which brings me to why I am talking about editors here today, when I don’t even deal with them anymore.

When I made the switch from romance to mysteries, my first book Dark of the Moon, was acquired by Kensington Books. Kensington is an independent, Manhattan-based family-owned publishing house. The editor who took me on was John Scognamiglio.

This year, John is being awarded the Mystery Writers of America Ellery Queen Award at the Edgar banquet. It is awarded to “outstanding writing teams and outstanding people in the mystery-publishing industry.”

It couldn’t happen to a nicer guy. Or a finer editor.

Now, all the folks at Kensington were grand to work with. When Kelly and I went to visit the Kensington offices, the Zacharius clan (the owners) treated us to a fabulous lunch. They got us blurbs and reviews and gave us a fabulous launch. The chairman of the board Walter Zacharius wrote a publicity letter praising our freshman book that began:

“I can count on the fingers of one hand those books which got me so excited that I couldn’t wait to urge all my friends and colleagues to read them right away. This means that Dark of the Moon is in select company.”

Then there was John.

He helped shape that debut book and all the others that followed. He was a line editor extraordinaire. In person, he’s quiet, taciturn. But on those revision letters that came, he was strong of voice, precise, and always spot-on with his criticisms. For our second book, Dead of Winter, his sharp eye helped us figure out a better ending with a great twist. The book got an Edgar nomination. And I’ll never forget his terse note on book three Paint It Black: “It’s too short.” He then proceded to help us find ways to beef up the plot and deepen the villain’s MO. The book made it to the New York Times list.

Maybe his best quality was that he believed in us, even when we didn’t believe in ourselves. He made us feel confident. He always made our books better.

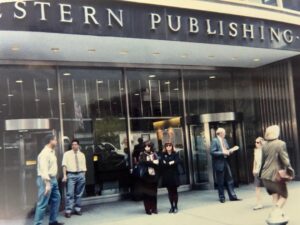

I wish I had kept some of his revision letters to us. They would have been fun, and instructive, to share with you, especially those of you who don’t have a great editor standing behind you. The best I have is this old photo of Kelly and me standing in front of headquarters the day the clan took us to lunch in 1998. (I had two bellinis!)

So here’s great editors. I so hope they are still out there amidst all the sturm und drang in publishing today. And to John, a very belated but heartfelt thanks. I’ll buy you a bellini when I see you.

My publisher, Severn House in London, uses the Oxford English Dictionary, or OED. It’s a little more staid that its American cousin, Merriam-Webster, but I love the research for its Word Stories.

My publisher, Severn House in London, uses the Oxford English Dictionary, or OED. It’s a little more staid that its American cousin, Merriam-Webster, but I love the research for its Word Stories.

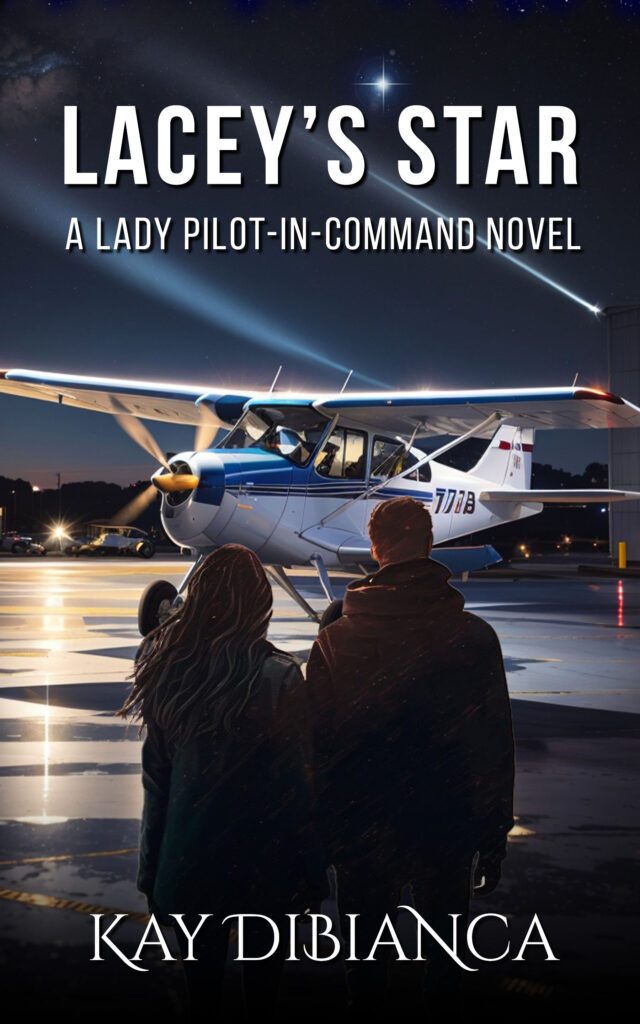

Happy to raise a glass to toast this partnership. May they enjoy many happy years together.

Happy to raise a glass to toast this partnership. May they enjoy many happy years together.