Okay. I expect some typer’s tension from this touchy topic. Plotters gonna hate. Pansters gonna say, “Yay!” And page-by-page cyclers with outline notes gonna go, “Meh. Nothin’ new. Was doin’ this all the time.” Writing into the dark, that is.

What’s writing into the dark? No, it’s not sitting in a room with the lights off and blindly searching for the keys. It’s a writing method that’s been around a long, long time and it involves going beyond seat-of-your-pants production.

That’s right. No outline. No vision. Just as I’m doing right now with pure exploration. Sure, I’ve done my research for this piece and have some crib notes of key points. I can’t imagine writing anything without some knowledge of what the post, essay, short story, novella, novel, or tome is going to be about. At least anything logical, that is.

Back up a sec, Garry, and explain plotting, pantsing, and page-by-paging for the newbies.

Plotting writers make detailed outlines of their work before they start. It’s like making blueprints for a house, and they rigidly follow those plans to a successful conclusion. Sure, there are a few change orders along the way, as there always are in house building. But for the most part, the end is always envisioned before breaking ground and starting construction.

Panster writers literally build by the seat of their pants. They also want a house built, but they love the freedom of working without permits or even drawings, except maybe on napkins. They dig a metaphoric hole, fill it with words, and fly at it—one word at a time until they hit “The End”. For some, pansting works. For others, it doesn’t.

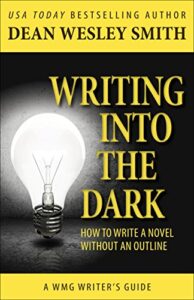

Page-by page cycling? That was a new term to me. It’s outlining as you go, or cycling back to correct mistakes every page or so. It was news to me until I got introduced to Dean Wesley Smith (DWS) and read his book Writing Into The Dark. Or was it?

Two things aligned at the same time to get me going on “writing into the dark”. One was from Harvey Stanbrough who’s a regular commenter here at the Kill Zone. Harvey is a prolific writer, to say the least, and he PM’d me to say, “Check out Writing Into The Dark.” Harvey also told me to check out Heinlein’s Rules for Writing, which I did, and that’s material enough for a whole other post. At the same time, I was video chatting with my good friend and UK indie writer, Rachel Amphlett. Rachel also recommended I read Writing Into The Dark as it’s become her novel-writing method.

Two things aligned at the same time to get me going on “writing into the dark”. One was from Harvey Stanbrough who’s a regular commenter here at the Kill Zone. Harvey is a prolific writer, to say the least, and he PM’d me to say, “Check out Writing Into The Dark.” Harvey also told me to check out Heinlein’s Rules for Writing, which I did, and that’s material enough for a whole other post. At the same time, I was video chatting with my good friend and UK indie writer, Rachel Amphlett. Rachel also recommended I read Writing Into The Dark as it’s become her novel-writing method.

Writing Into The Dark opens with Dean Wesley Smith saying this:

He spoke to me, and Dean kept me hooked in the book until the end. What I got out of Writing Into The Dark is realizing I’ve evolved or morphed over time from a plotter to a pantster to a page-by-page drafter who’s learned to speed things up through a process Dean Smith calls “cycling”. I have to say I’ve found my stride, and I’m very comfortable drafting an entire book by outlining as I go.

Before drilling into what page-by-page, cycling, and outlining-as-you-go entails, I want to deal with a very important part of the dark writing method. Dean goes into a bit of brain science and how it applies to plotters and pansters. Plotters generally apply the critical part of their thinking process. They want to know exactly what route they’re taking in driving through the story. Pansters apply creative brain function. They thrive on allowing creativity to flow by putting the creative side first but still allow the critical brain to keep watch. Critical brains stifle creative brains every time.

Dark writers say “Fu*k it. Critical brain stay home. Me ’n ole creativity here are goin’ for a ride and hang on to yer hat maggot, ’cause this is gonna take yer breath away!”

In Dean Smith’s writing method, he goes hard and fast with only short glimpses in the work mirror. He writes a page or two at a time (page-by-page), then quickly looks back, fixes whatever, and moves on. This he calls cycling through the manuscript. Write a page or two, cycle back, fix or edit, and do it again. Throughout his page-cycle rhythm, Dean keeps a notepad at his side where he jots down ideas and story points. This is his idea of an outline.

Besides reading Writing Into The Dark, I watched a video presentation Dean gave to a writers conference about his process. I also read an insightful interview with him, and I’ll snip some conversation from them. I feel Dean Wesley Smith is a master of dark writing technique (He’s written hundreds upon hundreds of books and pieces) so I’ll let him have a few words right here on the Kill Zone stage.

Besides reading Writing Into The Dark, I watched a video presentation Dean gave to a writers conference about his process. I also read an insightful interview with him, and I’ll snip some conversation from them. I feel Dean Wesley Smith is a master of dark writing technique (He’s written hundreds upon hundreds of books and pieces) so I’ll let him have a few words right here on the Kill Zone stage.

“Writing fast, writing a lot, and keeping on submitting changed the way I look at writing,” Dean says. “It changed my mindset. It taught me to trust my instincts and trust my voice. I left my voice in my stories because I didn’t rewrite everything into dullness. Rewriting kills your voice and your natural ability to tell a story.”

Dean goes on to say, “I hated the idea of writing sloppy, so when I realized something needed to be fixed, I went right back and fixed it. I developed the habit of cycling back every few hundred words and doing minor revisions, all the while keeping a handwritten outline of points beside me. But when I get to the end of the story, I leave it alone.”

Here is some advice from Dean Smith for emerging writers. “Focus on the story and moving ahead. Write more. Learn. Have fun. Keep learning and experimenting. Stop making it so serious. This is entertainment, so entertain yourself and have fun.”

I know there’s a lot of truth in Dean’s words because dark writing is working for me. I outlined the ever-living sh*t out of my first novel. It was planned like the D-Day Invasion of Normandy. Slowly—over time—I loosened up a bit. But things changed, big time, when I spent two years writing cranking commercial web content for my slave-driving daughter’s online writing business.

I know there’s a lot of truth in Dean’s words because dark writing is working for me. I outlined the ever-living sh*t out of my first novel. It was planned like the D-Day Invasion of Normandy. Slowly—over time—I loosened up a bit. But things changed, big time, when I spent two years writing cranking commercial web content for my slave-driving daughter’s online writing business.

That meat grinder doesn’t allow for much outlining. Not if you’re going to make money, that is. It’s research, write, proof, ship, and do it all over with a new topic that you’re really not all that hyped-up on. I wrote about everything from gastroenterology to bruxism to naturopathy treatments for foul-smelling vaginal secretions on a health & wellness site — to stainless steel vat technology in the hipster cottage brew industry.

Trust me. You want to get through this stuff as fast and with as little or no pain as possible. To survive and pay the bills, I got wired on dark writing. And I brought it with me when I went back to novels. Because you’re my friends, I’m going to show you my current writing method which is almost as dark as my subject matter and soul.

I’m working through a based-on-true crime series and releasing a new product every two months. Average lengths are about 52K words, and when I’m on a roll I write 900 to 1,000 words per hour. On a good day, when I’m not sidetracked by squirrels or severely hung over, I get-in about 3,500 words. So the calculator computes I draft a new book in about 15 writing days or 55 writing hours.

I don’t pre-outline anymore. I do exactly as Dean Wesley Smith does, and I didn’t know was it was called until Rachel and Harvey told me to read his book. Whadda ya know? Dean and I have something in common.

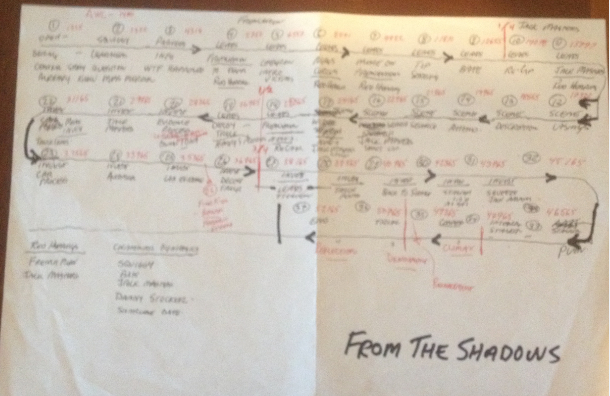

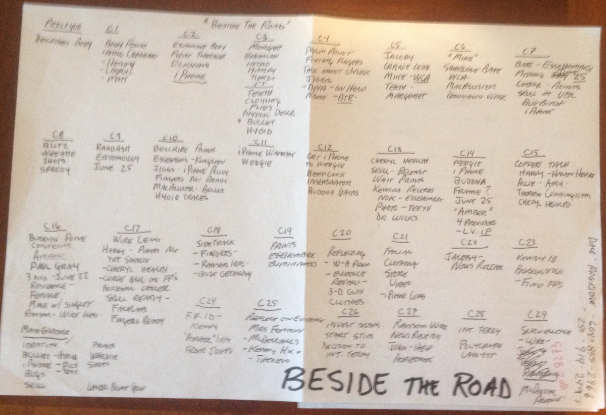

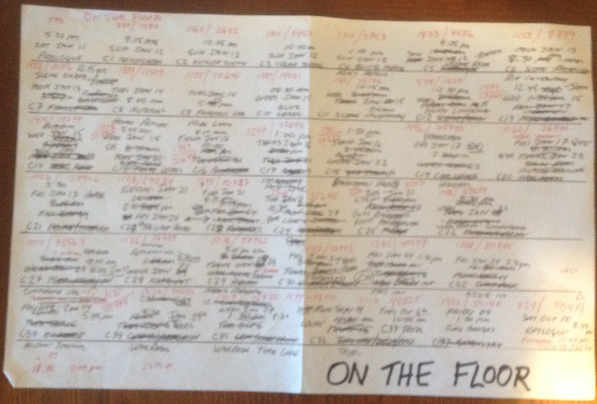

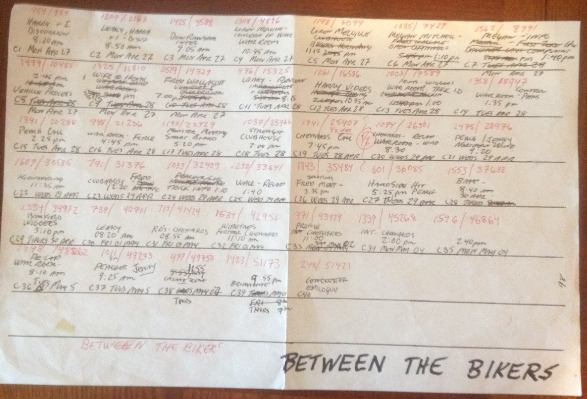

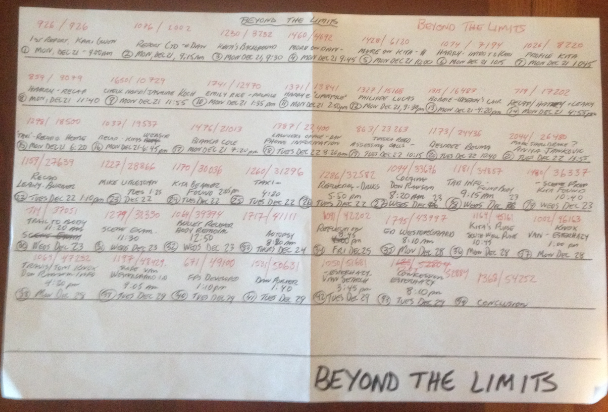

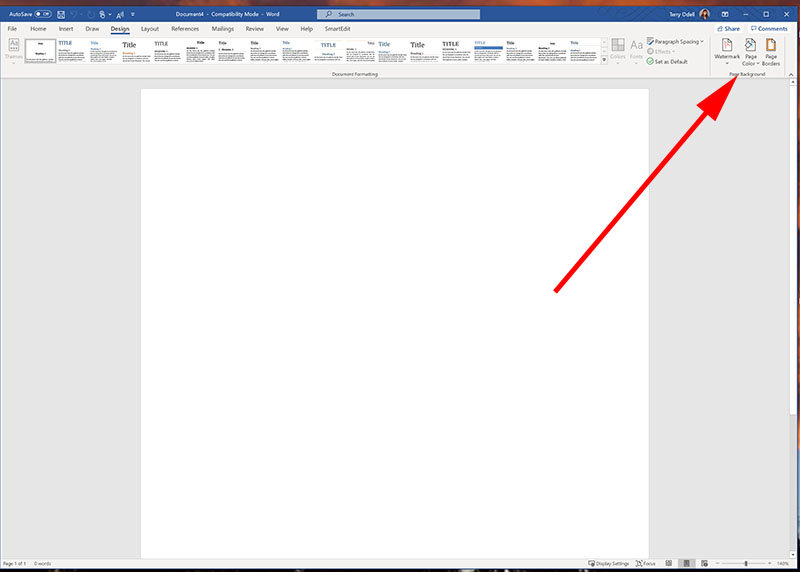

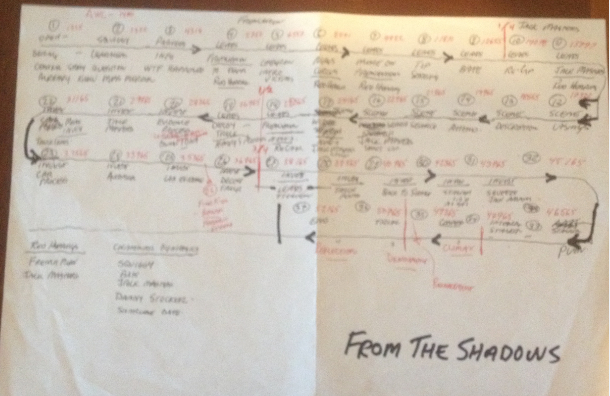

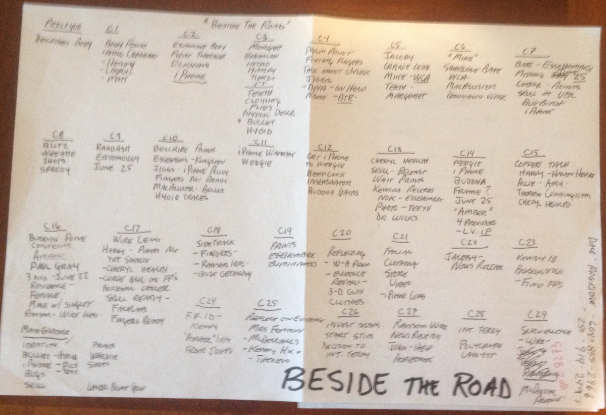

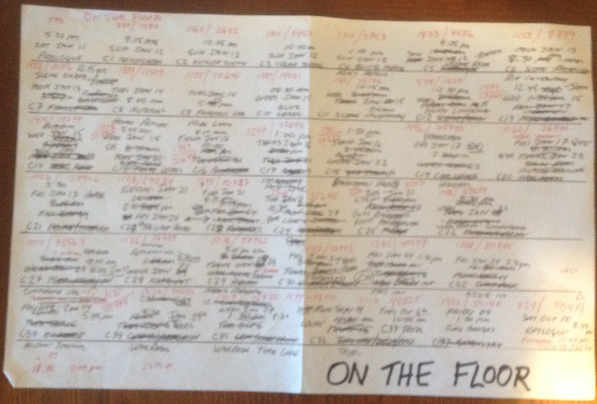

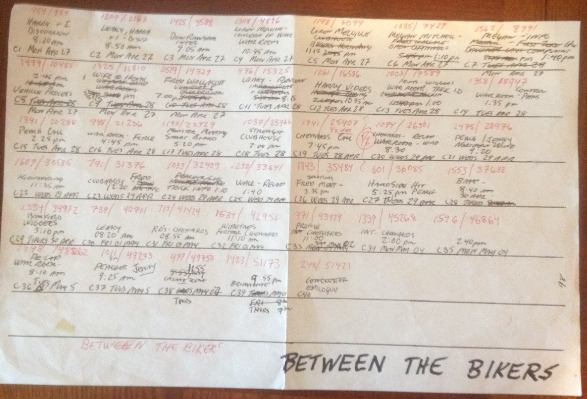

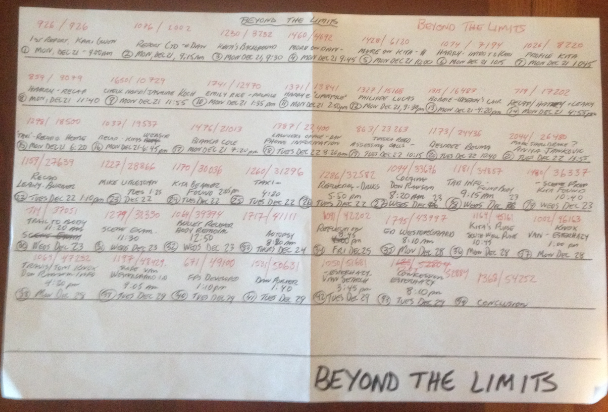

My outline emerges as I write chapter by chapter. I know where the story goes and how it ends because I lived in or around these crimes that I’m currently writing on. You gotta cut me some slack on internally knowing this series, but I’ll do the same on the next, which I plan to do in upcoming City Of Danger. What I do is keep a running log, or flow chart, on 11×17 paper. I’ll post the images so I don’t have to do any more describing than necessary. It’s the old picture being worth a thousand words thing.

See how my outline-as-I-go has evolved? I didn’t post pics of my first two in the series, In The Attic and Under The Ground. I didn’t use one for Attic, and I’ve lost the one for Ground. When I look at the progression through From The Shadows, Beside The Road, On The Floor, Between The Bikers, Beyond The Limits, and to my nearly-finished WIP At The Cabin, I see my method slightly changing. Hopefully, improving. I’ll let you know if it ever gets perfected, but don’t hold your breath.

You’re probably wondering what all those blurry swiggles and stimbols are. I outline-as-I-go from left to right and enter the chapter (scene) number, the date and time locaters, main plot points, the chapter word count (in red), and the overall story word count (in red) as it progresses scene by scene. That’s it. That’s how I keep track of a book’s gestation. The rest is mostly in my creative side except for research downloads and general hand-noted points similar to an editor’s style sheet.

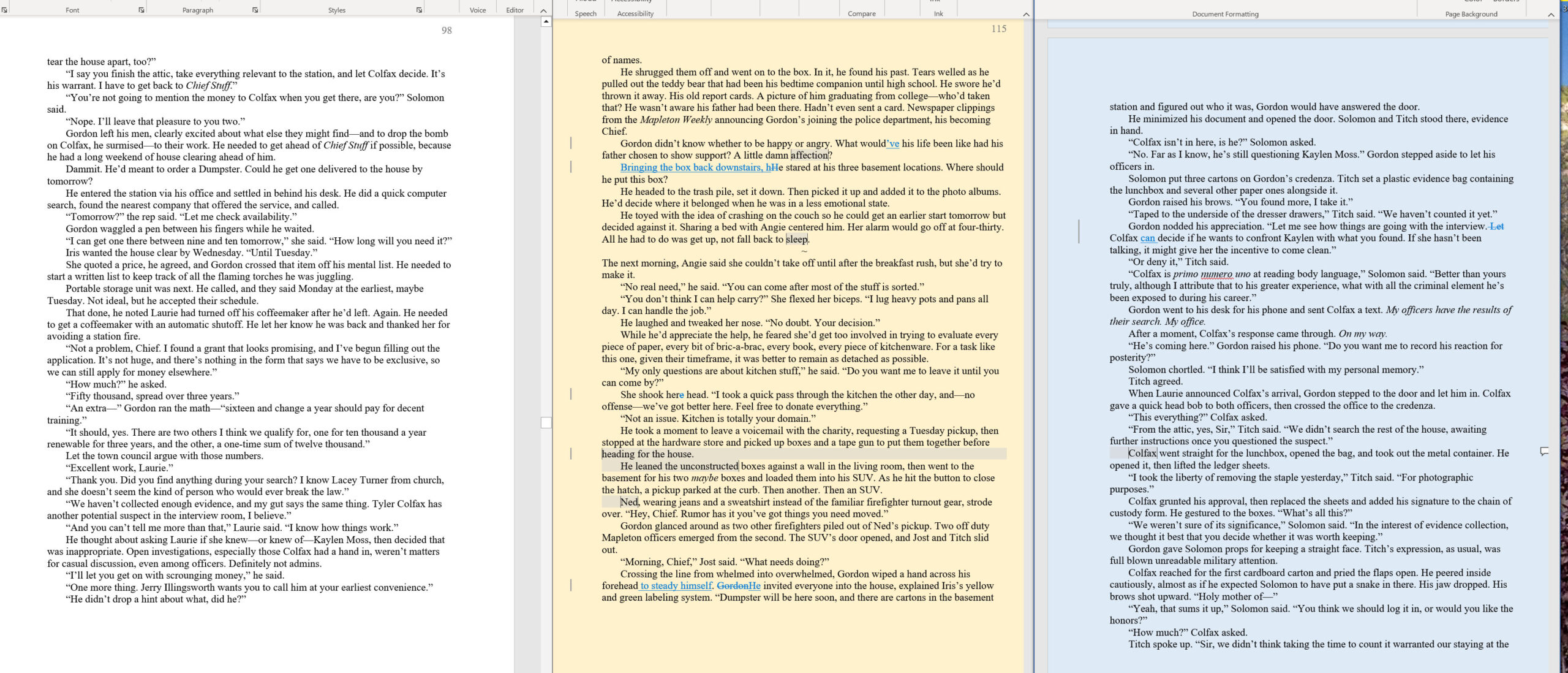

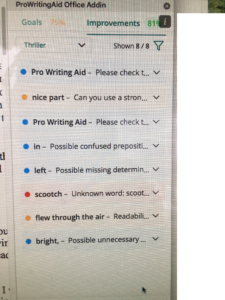

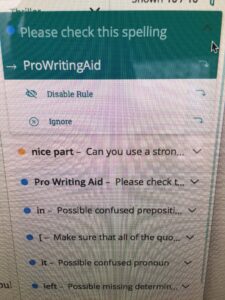

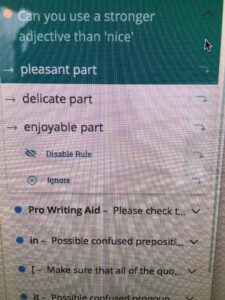

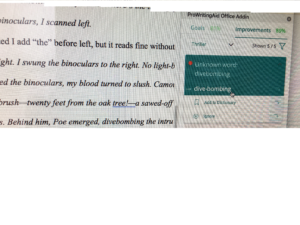

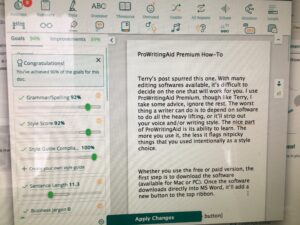

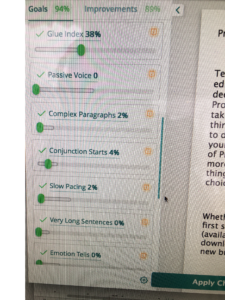

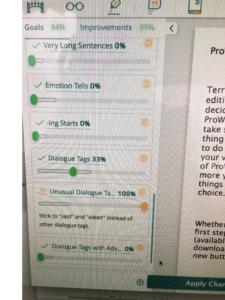

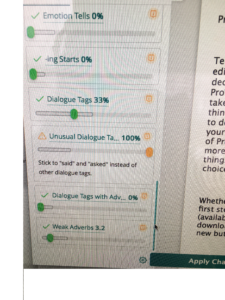

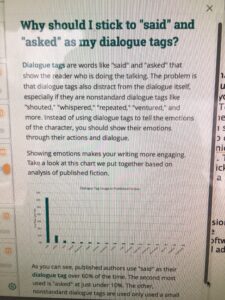

I used to do second-day editing where I’d go back over the previous day’s works, but I gave that up for what I figured out is cycling, as Dean Smith calls it. Once I get to the end, I run it through Grammarly and clean it up. Then it’s off to my proofreader who does a remarkable job of finding issues, even teeny-tiny mistakes. Oh, BTW, I write each chapter/scene on a separate Word.doc and assemble them into one full manuscript as I do the Grammarly edit.

That’s it. I’m not saying my way of writing into the dark is right or wrong. It’s just an option I thought I should share. You do what works for you, but make sure you do one thing right. That’s to keep on writing and putting it out there, just as Heinlein’s rules prescribe.

It’s your turn, Kill Zoners. Am I out to lunch with this reckless behavior? Have you tried dark writing? Tell us in the comments what your style is, and your outlining experiences are.

——

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective—an old murder cop—who went on to another career as a coroner handling forensic death investigations. Now, Garry’s returned from the bowels of the morgue and arose as an internationally bestselling crime writer. True story & he’s sticking to it.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective—an old murder cop—who went on to another career as a coroner handling forensic death investigations. Now, Garry’s returned from the bowels of the morgue and arose as an internationally bestselling crime writer. True story & he’s sticking to it.

Garry is also an indie publisher currently finishing a 12-part, based-on-true-crime series detailing investigations he was involved in. Garry Rodgers runs a popular blog site at DyingWords.net and messes around on Twitter. When not writing into the dark, Garry spends time putting around the saltwater near his home on Vancouver Island in British Columbia on Canada’s Covid free infested southwest coast.

Peace in Mapleton doesn’t last. Police Chief Gordon Hepler is already juggling a bitter ex-mayoral candidate who refuses to accept election results and a new council member determined to cut police department’s funding.

Peace in Mapleton doesn’t last. Police Chief Gordon Hepler is already juggling a bitter ex-mayoral candidate who refuses to accept election results and a new council member determined to cut police department’s funding. Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

And I really created extra work for myself this time around, because I didn’t write chapter summaries and time stamps as I finished each chapter. My bad. So, as I’m reading and marking up my printouts—and adding more sticky notes as I run across things that need elaboration or deleting—I’m also writing my chapter summaries. Longhand. I hope I can read them when the time comes!

And I really created extra work for myself this time around, because I didn’t write chapter summaries and time stamps as I finished each chapter. My bad. So, as I’m reading and marking up my printouts—and adding more sticky notes as I run across things that need elaboration or deleting—I’m also writing my chapter summaries. Longhand. I hope I can read them when the time comes! Shalah Kennedy has dreams of becoming a senior travel advisor—one who actually gets to travel. Her big break comes when the agency’s “Golden Girl” is hospitalized and Shalah is sent on a Danube River cruise in her place. She’s the only advisor in the agency with a knowledge of photography, and she’s determined to get stunning images for the agency’s website.

Shalah Kennedy has dreams of becoming a senior travel advisor—one who actually gets to travel. Her big break comes when the agency’s “Golden Girl” is hospitalized and Shalah is sent on a Danube River cruise in her place. She’s the only advisor in the agency with a knowledge of photography, and she’s determined to get stunning images for the agency’s website. Like bang for your buck? I have a

Like bang for your buck? I have a

Besides reading Writing Into The Dark, I watched a video presentation Dean gave to a writers conference about his process. I also read an insightful interview with him, and I’ll snip some conversation from them. I feel Dean Wesley Smith is a master of dark writing technique (He’s written hundreds upon hundreds of books and pieces) so I’ll let him have a few words right here on the Kill Zone stage.

Besides reading Writing Into The Dark, I watched a video presentation Dean gave to a writers conference about his process. I also read an insightful interview with him, and I’ll snip some conversation from them. I feel Dean Wesley Smith is a master of dark writing technique (He’s written hundreds upon hundreds of books and pieces) so I’ll let him have a few words right here on the Kill Zone stage. I know there’s a lot of truth in Dean’s words because dark writing is working for me. I outlined the ever-living sh*t out of my first novel. It was planned like the D-Day Invasion of Normandy. Slowly—over time—I loosened up a bit. But things changed, big time, when I spent two years

I know there’s a lot of truth in Dean’s words because dark writing is working for me. I outlined the ever-living sh*t out of my first novel. It was planned like the D-Day Invasion of Normandy. Slowly—over time—I loosened up a bit. But things changed, big time, when I spent two years

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective—an old murder cop—who went on to another career as a coroner handling forensic death investigations. Now, Garry’s returned from the bowels of the morgue and arose as an internationally bestselling crime writer. True story & he’s sticking to it.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective—an old murder cop—who went on to another career as a coroner handling forensic death investigations. Now, Garry’s returned from the bowels of the morgue and arose as an internationally bestselling crime writer. True story & he’s sticking to it.