Some days, I sit down to write and wonder what the hell I’m doing.

The words don’t flow. The structure feels off. My confidence has left the building and is probably sitting at a pub somewhere ordering beer, wings, and nachos without me.

You’d think after years in law enforcement, forensics, and now crime writing, I’d be bulletproof by now—impervious to self-doubt and rejection. But nope. There are days I feel like a cracked pot.

And that, my fellow Kill Zoners, brings me to a story I want to share with you. It’s an old one. A quiet one. But it says everything a writer needs to hear.

The Story of the Cracked Pot

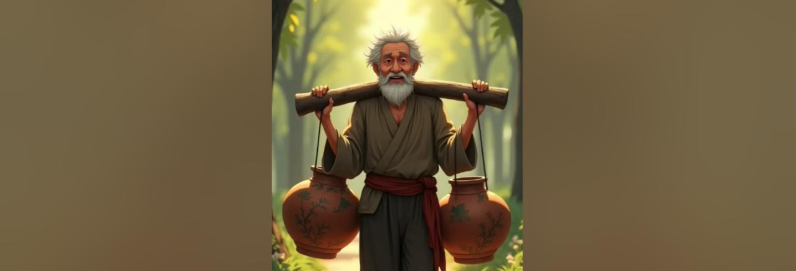

There was an old man who lived in a village in India. Every morning, he would place a long stick across his back, hang a water pot from each end, and walk several miles to the river to get fresh water for his family.

But the two water pots were not the same. One had a series of small cracks in its side, causing it to leak.

The old man would fill both pots at the river, but by the time he got back to his home, the cracked pot would be half empty, the water having leaked out during the walk.

The cracked pot grew increasingly ashamed of its inability to complete the task for which it was made. One day, while the old man filled the two pots at the river, the cracked pot spoke to him.

“I’m sorry. I’m so embarrassed that I cannot fulfill my responsibilities as well as the other pot.”

The old man smiled and replied, “On the walk home today, rather than hanging your head in shame, I want you to look up at the side of the path.”

The cracked pot reluctantly agreed to do as the old man asked. As they left the riverbank and started on the path, he couldn’t believe his eyes.

On his side of the path was a beautiful row of flowers.

“You see,” the old man said, “I’ve always known you had those cracks, so I planted flower seeds along your side of the path. Each day, your cracks helped me water them. And now, I pick these flowers to share their beauty with the entire village.”

We All Leak a Little

That story gets me every time.

Because if you’ve ever tried to create something from nothing, to sit at a keyboard and bring life to characters who don’t exist yet, then you know what it means to question your usefulness. You know what it feels like to compare yourself to someone else’s perfect pot—and wonder why your own words keep leaking out, incomplete, imperfect, maybe even irrelevant.

But what if your cracks are the very thing that make your writing beautiful?

What if the years you spent doubting yourself taught you empathy—and now your characters breathe with it?

What if the rejections, the self-edits, the tough critiques… what if those watered something beside the path you just haven’t noticed yet?

I’m not here to hand you a participation ribbon or pat your head and say, “You’re special.” You already know writing is hard. It takes guts. It takes sitting with discomfort and pushing through.

But I am here to tell you that those imperfections you think are holding you back?

They’re feeding the flowers.

Keep Leaking

Maybe your story structure feels like a mess. Maybe your plot sagged in Act Two and hasn’t recovered. Maybe someone told you you’d never make it—and part of you believed them.

Here’s what I want you to remember.

There is no perfect pot.

Even the bestselling author you admire struggles with the page. Even the literary genius has doubt gnawing at the back of their brain. The difference is, they kept walking the path. Cracks and all.

And if you do the same—keep showing up, keep pouring yourself into the process, keep leaking a little water every day—you’ll be amazed at what grows.

You don’t have to be flawless to be useful. You don’t have to be brilliant to be beautiful. And you sure as hell don’t need to write like anyone else to make an impact.

You just need to walk your path.

Let the seeds you’ve planted over the years—your discipline, your voice, your scars, your strange and wonderful perspective—be watered by your imperfections.

Keep writing.

You have no idea how many flowers are blooming because of you.

Kill Zoners – Show us your cracks.