Today’s guest post is from longtime Kill Zone supporter and frequent commenter, Harvey Stanbrough. Harvey is a prolific (now that’s an understatement) writer and publisher who’s here to share his thoughts and experiences on Heinlein’s Rules for Writers and other interesting things… like writing Into the dark and cycling.

When Garry Rodgers invited me to write a guest post about Heinlein’s Rules for TKZ, as an adherent of the Rules and a long-time follower of TKZ, I was flattered. I considered simply offering up my annotated Heinlein’s Business Habits for Writers, but that didn’t feel like enough. It’s more of a what-to-do updated for the 21st century. It says nothing about why-to-do.

What follows is an excerpt from a compilation of five posts from my instructive almost-daily Journal. These posts comprise a would-be interview about Heinlein’s Business Habits for Writers and why, as a professional fiction writer, I personally find them essential.

This series was first published on my instructive from March 8 – March 12, 2021 at https://hestanbrough.com. You can download the entire article in PDF, free, by clicking https://harveystanbrough.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/What-Heinleins-Rules-Mean-to-Me.pdf.

Topic: Awhile Back: An Introduction to a Series on Heinlein’s Rules

Awhile back, I received a note from a writer who wanted to interview me about my adherence to Heinlein’s Rules. The purpose was so the writer could put up a blog post on the topic.

Later, the writer decided the post would be too long for their format. I agreed.

But the questions the writer asked, and the incidental comments the writer made, were absolutely typical (usually even word for word) of the questions and comments I’ve heard from writers at conferences and conventions for the past thirty years.

So I decided to use that writer’s questions and comments to post a series of topics here for the benefit of the few who read this Journal. Note: If the writer emails me to ask me to take this post down, I will do so. Then I will paraphrase the questions and comments and continue the series.

Some of this will hit home. Some of it might make you angry. Some of it will sound repetitious. I don’t mean any harm. In fact, I’ve added a disclaimer to the very end of every post now to maybe help satisfy detractors.

In my own experience, I’ve often found I had to hear something more than once or hear it said in a different way before I finally got it. It is in that spirit that I offer this and the following few posts on Heinlein’s Rules and Writing Into the Dark, which really do go hand in hand.

First, here are Heinlein’s Rules so we’re all starting from the same place. As I’ve said many times, you can download a free PDF copy of Heinlein’s Rules (annotated) by clicking https://harveystanbrough.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Heinleins-Business-Habits-Annotated-2.pdf.

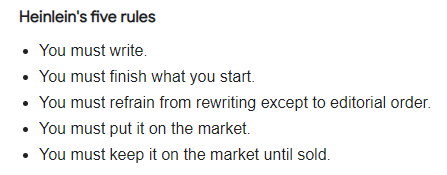

Heinlein first outlined his rules in Of Worlds Beyond: The Science of Science Fiction Writing. Largely as an afterthought to his article, he wrote the following:

“I’m told that these articles are supposed to be some use to the reader. I have a guilty feeling that all of the above may have been more for my amusement than for your edification. Therefore I shall chuck in as a bonus a group of practical, tested rules, which, if followed meticulously, will prove rewarding to any writer.”

Then he lists what he calls his Business Habits:

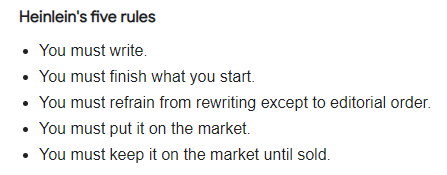

- You must write.

- You must finish what you start.

- You must refrain from rewriting except to editorial order.

- You must put it on the market.

- You must keep it on the market until sold.

Note: Heinlein also add that if you follow these rules, eventually you would find some editor (reader) somewhere who would buy your work. Nothing could be more spot-on the money.

Here are some excerpts from the rest of the writer’s introduction, which contain some of those “typical” questions and comments I alluded to earlier and my responses:

Q: “It stands to reason that if we, as writers, spend the bulk of our time writing, we’re only going to improve. And if, instead of hopping from unfinished project to unfinished project or obsessing over a work to the point of ridiculousness, we move on to the next story, we’re going to spend more time writing. Which is the one thing we all need to do a lot of to succeed.”

Harvey: I agree in principle with this point. Instead of “hopping from unfinished project to unfinished project or obsessing over a work” at all, we should write the current story (even the very first) to the best of our ability, then publish it and move on to the next story.

But this isn’t only so we’ll “spend more time” writing. Writing a lot without learning and practice will not help you succeed. Practice (vs. hovering via revisions and rewrites) is what will help you succeed. To practice, you learn and then apply what you learned in the next story.

Never look back. Always look forward to the next technique to learn and the next story to write.

Q: “I have a few concerns with some of the rules to the point that I’ve never been able to embrace the process. … I’ve always wished I knew someone personally who follows Heinlein Rules so I could talk to them and see what they would say about my concerns.”

Harvey: You came to the right place. I was exactly the same way. Exactly. Which is to say I was filled with unreasoning fear. Unreasoning because there are no real consequences to writing a “bad” (in your opinon) story. The truth is, the world won’t stop if you write a “bad” story and not that much good will happen if you write a “good” (again, in your opinion) story. Your opinion of your work is still only one opinion.

To you, your original voice is boring because it’s with you 24/7. But to others, your original voice is unique and fresh. Given the chance to read your story, some will love it, some will hate it, and the majority will enjoy it—if you don’t polish your original voice off it.

Topic: Post 2 in the Heinlein’s Rules Series

Actually, more introductory stuff today, with some specifics on Heinlein’s Rules mixed in.

Q: To provide context, how long have you been using this process, how many books/stories have you been able to write, and what kind of success have you achieved?

Harvey: I first discovered Heinlein’s Rules and a technique called Writing Into the Dark in February 2014. I made the conscious decision to pull up my big boy pants and give it an honest try. And frankly I was amazed. Since then I’ve written over 220 short stories, 8 novellas and 70 novels. (And I didn’t write for almost 2 years of that time.)

That’s the real secret to Heinlein’s Rules and Writing Into the Dark, if there is a secret: You have to dedicate yourself to pushing down your fears and really trying it for yourself. It helps to realize you have absolutely nothing to lose and everything to gain. You can always go back to writing the “old” way: outlining, revising, critique grouping, rewriting however many times, etc.

I started with short stories (one a week) and ended that streak with 72 short stories in 72 weeks, all written in accordance with Heinlein’s Rules, all written into the dark.

If you look at a mean average, that’s just over 8 novels per year for 7 years and just over 28 short stories per year in that same time period, plus 8 novellas scattered in.

But I expect to produce a lot more this year. I finished my 58th novel on March 2, but it was also the 4th novel I started and completed this year. So on average, I’m on track to write 20 novels this year alone. All because I found Heinlein’s Rules and Writing Into the Dark, pushed my fears down and really tried them. The trust in the process came quickly after that.

My success is because I learn and then I write. I don’t hover. I use a process called “cycling” as I write. Some call it revision, but revision is a conscious-mind process and cycling is a creative-mind process. That’s the big difference, and it’s all-important.

Q: And what is “cycling”?

Harvey: When I return for the next writing session, I read what I wrote during the previous session. But I read as a reader, just enjoying the story, not critically as a writer. And I allow myself and my characters to touch the story as I go. When I get back to the blank space, I’m back into the flow of the story and I just keep writing.

I mentioned that I finished my 58th novel on March 2. On March 3 I started my 59th. I’m not quite 27,000 words into that one. My daily word count goal is 4,000 words of publishable fiction per day, but that’s only 4 hours out of the 24 that we are given in each day. In that regard, and measured against the old pulp writers (who wrote on manual typewriters) I am a total slacker.

Q: I’ve heard many (not all) writers who adhere religiously to Heinlein’s Rules poo-poo the things writers often do to improve their craft, such as attending conferences, reading books and blogs, taking courses, etc. I understand, I think, the principle here, that if you spend too much time doing those things, you’re not doing the actual writing. But there are some things that writing alone can’t fix; sometimes we need direct instruction from people who’ve been there to identify what’s wrong and learn how to address those issues. What are your thoughts on continuing education as an author?

Harvey: Not to be contrary, but on this point I have to disagree. I’ve never heard a writer who adheres to Heinlein’s Rules “poo-poo” doing anything to improve their craft. In fact, all of them stress learning as only a very close second in importance to actually writing.

That said, even a decade or so before the CovID panic, actual physical conferences were falling by the wayside, leaving only large, often unaffordable conferences. But I personally have always urged writers to attend conferences and even the much more affordable conventions that interested them, for networking opportunities if nothing else.

Today most of those opportunities are virtual, a concept I have trouble grasping. I need the physicality and the immediate back and forth between actual people. That said, I still recommend even virtual conferences if that’s something the writer is interested in.

Re reading books and blogs on writing, of course I recommend those and I don’t know of anyone who doesn’t. In fact, I often provide links to other resources in my Journal. And my author website at HarveyStanbrough.com is rich with writer resources.

My own personal caveat is that the writer should exercise due caution and check out the author of the book or blog. For example, if that person doesn’t write novels, s/he has no business teaching others how to write novels. Would you go to a car mechanic to learn the finer points of carpentry or medicine? And re taking courses, I urge writers to do so, again after investing the time to do due diligence.

The process I recommend is this: The aspiring or beginning or experienced fiction writer should

- write every story to the best of their current ability, not revise and rewrite their original voice off it, then publish it.

- take time to attend a class or lecture (online is fine) and then stick one technique they want to practice in the back of their mind when they start writing the next story and practice it as they write that story.

- then write that story to the best of their current ability, not revise and rewrite their original voice off it, then publish it.

Q: How easy is it for you to follow the rules?

Harvey: I find it extremely easy to follow HR1, 2, and 3. I’m dedicated to a daily word count goal of 4,000 words of publishable fiction (no drivel). Re HR1 and 2, I’m a fiction writer, so I write as part of my daily routine.

Re HR3, I don’t even allow my own critical, conscious mind into my work, so even the thought of allowing someone else to tell me how to “fix” the story that came out of my mind is ludicrous to me. As I’ve alluded to before, Rule 4 is the most difficult for me to follow because I’d much rather be writing the next story.

# # #

To read the rest of this article, download the free PDF: https://harveystanbrough.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/What-Heinleins-Rules-Mean-to-Me.pdf.

# # #

Bio:

Harvey Stanbrough was born in New Mexico, seasoned in Texas and baked in Arizona, so he’s pretty well done. For a time, Harvey wrote under five personas and several pseudonyms, but he takes a pill for that now and writes only under his own name. Mostly.

Harvey Stanbrough was born in New Mexico, seasoned in Texas and baked in Arizona, so he’s pretty well done. For a time, Harvey wrote under five personas and several pseudonyms, but he takes a pill for that now and writes only under his own name. Mostly.

Harvey is a prolific professional fiction writer by pretty much any standard. In just over 6 years he’s written over 70 novels, 8 novellas, and around 220 short stories across several genres.

He’s also compiled around 30 short story collections and several lauded, major-prize-nominated poetry collections and nonfiction books on the craft of writing. That is in addition to his hundreds of articles, essays and blog posts.

To see Harvey’s work visit StoneThreadPublishing.com or his author website at HarveyStanbrough.com. If you’re a writer and would like to increase your productivity, visit his instructive daily Journal on writing at HEStanbrough.com. You can contact Harvey directly at harveystanbrough@gmail.com.

Oh, as a bonus, you can read about Harvey’s personas at https://harveystanbrough.com/my-personas/. Each has his or her own brief bio

Harvey Stanbrough was born in New Mexico, seasoned in Texas and baked in Arizona, so he’s pretty well done. For a time, Harvey wrote under five personas and several pseudonyms, but he takes a pill for that now and writes only under his own name. Mostly.

Harvey Stanbrough was born in New Mexico, seasoned in Texas and baked in Arizona, so he’s pretty well done. For a time, Harvey wrote under five personas and several pseudonyms, but he takes a pill for that now and writes only under his own name. Mostly.

So Tom Brady has retired. He’s one of the few superstars who managed to go out on top and on his own terms. So many others have hung on past their primes as we averted our eyes—Joe Namath hobbling around on two bad knees for the Rams; Shaquille O’Neal lumbering up and down the court like a bear stuck with a tranquilizer dart (in a Celtics uniform yet!); Muhammad Ali getting his clock cleaned by Larry Holmes (who cried after what he’d done to his hero).

So Tom Brady has retired. He’s one of the few superstars who managed to go out on top and on his own terms. So many others have hung on past their primes as we averted our eyes—Joe Namath hobbling around on two bad knees for the Rams; Shaquille O’Neal lumbering up and down the court like a bear stuck with a tranquilizer dart (in a Celtics uniform yet!); Muhammad Ali getting his clock cleaned by Larry Holmes (who cried after what he’d done to his hero).

Besides reading Writing Into The Dark, I watched a video presentation Dean gave to a writers conference about his process. I also read an insightful interview with him, and I’ll snip some conversation from them. I feel Dean Wesley Smith is a master of dark writing technique (He’s written hundreds upon hundreds of books and pieces) so I’ll let him have a few words right here on the Kill Zone stage.

Besides reading Writing Into The Dark, I watched a video presentation Dean gave to a writers conference about his process. I also read an insightful interview with him, and I’ll snip some conversation from them. I feel Dean Wesley Smith is a master of dark writing technique (He’s written hundreds upon hundreds of books and pieces) so I’ll let him have a few words right here on the Kill Zone stage. I know there’s a lot of truth in Dean’s words because dark writing is working for me. I outlined the ever-living sh*t out of my first novel. It was planned like the D-Day Invasion of Normandy. Slowly—over time—I loosened up a bit. But things changed, big time, when I spent two years

I know there’s a lot of truth in Dean’s words because dark writing is working for me. I outlined the ever-living sh*t out of my first novel. It was planned like the D-Day Invasion of Normandy. Slowly—over time—I loosened up a bit. But things changed, big time, when I spent two years

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective—an old murder cop—who went on to another career as a coroner handling forensic death investigations. Now, Garry’s returned from the bowels of the morgue and arose as an internationally bestselling crime writer. True story & he’s sticking to it.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective—an old murder cop—who went on to another career as a coroner handling forensic death investigations. Now, Garry’s returned from the bowels of the morgue and arose as an internationally bestselling crime writer. True story & he’s sticking to it.