By Elaine Viets

Like most writers, I love words. I like to read about them, learn new ones, find old ones. I enjoy puns and wordplay. Naturally, I depend on my dictionaries. But did you know these websites are crammed with extra information?

These days, dictionaries are much more than spelling and definitions.

Here are two of my favorite online sites.

Merriam-Webster dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/

This site usually has a topical essay about words.

After the untimely death of Catherine O’Hara, who left her mark on movies such as Home Alone and TV’s Schitt’s Creek, Merriam-Webster had an essay on 16 words from Schitt’s Creek. The Canadian sitcom is about “the Roses, a rich family that loses its wealth and must temporarily move into a motel in a small town with the cheeky name of Schitt’s Creek,” Webster said. “By metrics of awards and international viewership, Schitt’s Creek became Canada’s most successful television series. Among the series’ memorable characters is Moira Rose, played by the late Catherine O’Hara, whose diction is, shall we say, a bit eccentric.”

One of the best words Moira used is bombilate, which means, “to buzz or drone.”

“The room is suddenly bombilating with anticipation,” Moira said.

Too bad her wonky usage of bombilate isn’t popular enough to make Webster’s. Other Moira words include Balaton, confabulate and dangersome.

I have problems sorting out affect and effect. I can’t keep those words straight. Or is it strait? Webster has this helpful article: “Affect vs. Effect and how to pick the right one.”

“The basic difference is this: affect is usually a verb, and effect is usually a noun,” Webster said. Much more useful than what my teachers told me: “An affect has an effect.” Huh?

Webster delves into the proper use of em-dashes, en-dashes and hyphens and has a list of top word look-ups. Here’s one: Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg. That’s a lake, and it’s in the US, not Wales. The lake has the longest place name in our country. There are various stories about the name’s origin, but one says the name is Native American and commemorates an 18th-century fishing treaty. It’s jokingly translated as: “You fish on your side, I fish on my side, and nobody fishes in the middle.” The lake is in Webster, Mass., and many just call it Lake Webster.

Webster (the dictionary) has a helpful section on slang and trending words.

Know what a fridge cigarette is? “A cold, refreshing and addictive soft drink.” Gruzz is an older person. (I hope that one doesn’t catch on.) An almond mom is “a mother who pushes her daughter to be skinny, through diet.” Note that the term refers to daughters, not sons, enforcing expectations that women have to be thin. Bed rotting mean staying in bed all day. Zaddy is an attractive older man. There are more, lots more slang words Webster is watching. They’re fun to explore.

Webster also features words with tricky pronunciations, including ragout. Don’t embarrass yourself by calling that meaty stew rag-out. It’s ra-GOO.

Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford English Dictionary

My publisher, Severn House in London, uses the Oxford English Dictionary, or OED. It’s a little more staid that its American cousin, Merriam-Webster, but I love the research for its Word Stories.

My publisher, Severn House in London, uses the Oxford English Dictionary, or OED. It’s a little more staid that its American cousin, Merriam-Webster, but I love the research for its Word Stories.

Here’s part of the story of glamor. Excuse me, glamour.

“The schoolroom, verb tables, and Latin class seem about as far removed from our current notion of glamour as it’s possible to get,” the OED said. But grammar and glamour “were originally the same word.”

Dull, dusty grammar “first came into English from French with the meaning ‘learning or scholarship concerning a language’, and particularly, ‘a book which contains this knowledge’. The word soon extended to the principles of any kind of learning, and to books setting out such principles.”

Grammar took a turn into the occult, and words related to grammar began to refer to “knowledge of or expertise in magic and astrology, or to manuals for invoking demons and performing general sorcery.” These words included “gramarye and grimoire . . . and, finally, glamour.”

“Since glamour entered the language it’s taken on quite the life of its own.” It’s given us “glamour puss, (a glamorous or attractive person), glamazon, (a tall, glamorous, and powerful woman), and glampsite, (a campsite for glamping – the more luxurious way to camp).”

You can subscribe to the OED, but if you can’t afford a hundred bucks, you can still look up words for free, and enjoy word lists, world English, and the history of English.

Wordsmith Tom Stoppard wrote, “I don’t think writers are sacred, but words are. They deserve respect. If you get the right ones in the right order, you might nudge the world a little or make a poem that children will speak for you when you are dead.”

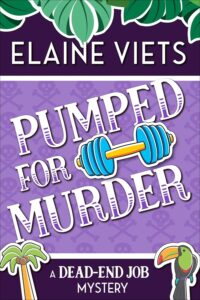

International sale: Two Dead-End Job mysteries, “Dying to Call You” and “Pumped for Murder” are $1.99 today at bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Google, Kobo, Apple and Amazon in the US and Great Britain.

Is 2026 the year you want to learn to write fascinating villains and antagonists? Please check out Debbie Burke’s bestselling craft guide, The Villain’s Journey-How to Create Villains Readers Love to Hate.

Is 2026 the year you want to learn to write fascinating villains and antagonists? Please check out Debbie Burke’s bestselling craft guide, The Villain’s Journey-How to Create Villains Readers Love to Hate.

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets