by Debbie Burke

@burke_writer

Photo credit: Flickr CC by 2.0

As a kid, I played the Clue board game, but otherwise I don’t know much about gaming. When mystery dinner parties recently crossed my radar, I became curious. A game night with drinks, dinner, and a crime to solve sounded intriguing. As a writer, I wondered:

Who writes the scripts?

Where do you find them?

How do mystery dinners work?

Is script writing a worthwhile option for authors to try?

To answer these questions, I snooped around a Florida snowbird community where a mystery dinner party had been held a couple of weeks ago.

The party hosts are Suzanne and Michael Fitzsimmons, originally from Colorado where they planned social events at a club they owned. After snow-birding for several years, they moved to Florida permanently and host frequent mystery dinners with varied themes. Suzanne says, “It’s a good way for casual acquaintances to become friends and bring the community closer together.”

Before sending invitations, Suzanne talks with residents to match personalities with roles.

That led to my interviews with four party guests.

Judie and Dru Gilliland are retired farmers from Ohio. Judie describes herself as being on the shy side although she’s not shy about her alma mater Ohio State (“Go Buckeyes!”). Their daughter describes Dru’s personality: “Dad could be in the middle of China and he’d find someone he knew.”

Kristen and Joe MacLellan live on Prince Edward Island, Canada and spend winters in Florida. Before retirement, Kristen owned a day care and Joe was a bank manager. Initially Kristen was reluctant to accept the party invitation because of shyness but said, “Joe was all over it like a dirty shirt.” Their nine grandkids call him the “Silly Grandad.”

Parties are built around themes and holidays like a Halloween haunted house, Scrooge’s Christmas murder, a cruise ship, and even a Hillbilly Wedding. Suzanne buys mystery game sets that include scripts, character roles, and descriptions.

She caps the guest list at eight to 10 people. Then she sends invitations that assign each person to play a character and suggests costumes. According to Judie, thrift shops are excellent places to shop for those outfits.

The setting for this party is a Napa Valley vineyard during a wine festival. Five years before, the vineyard’s owner Barry Underwood disappeared and the body had been buried under the wood floor in the wine cellar (humorous names are mandatory). When an earthquake destroys the floor, the body is revealed, and party guests must solve the crime.

Suspects include:

Ralph Rottingrape, the victim’s cousin who took over running the vineyard after Underwood’s disappearance.

Otto Von Schapps, played by Dru. He’s a loud, boisterous German wine merchant who wears lederhosen and suspenders and flashes lots of cash. “Perfect part for him,” Judie says. “Except I don’t flash cash,” Dru adds.

Kristen MacLellan as Marilyn Merlot

Kristen plays Marilyn Merlot whose costume is a billowy white dress, platinum wig, and long gloves. In this photo, Kristen’s shyness is forgotten as she recreates the famous scene from Seven Year Itch. “Too bad the fan wasn’t up to the task,” she laments.

Two characters are assigned to play the sleuths:

Joe is Bud Wizer, an FBI agent with beer logos on his t-shirt and cap. He’s armed with a six-pack.

Bud Wizer and Marilyn Merlot

Judie is Bonnie Lass, a Scottish mystery author, making her ideally suited to solve crimes. She wears a tartan skirt, knee socks, and a narrow brim fedora.

During cocktail hour, host Michael bartends while Suzanne hands out booklets for guests to read that outline the plot.

Over salad, characters introduce themselves and read their part of the script. Each receives an envelope containing a clue that’s unique to that character. All have motives for murder, but only the killer knows his or her identity and that person reads from a different script.

While dinner goes on in a light-hearted atmosphere, characters warm to their roles with accents, flamboyant gestures, and ad libs. Joe improvised by adding a blackmail subplot that wasn’t in the script.

After dessert, everyone tries to guess the killer’s identity. At this party, only Dru and Judie guessed correctly. The identity was revealed to me but, sorry, I’m sworn to secrecy.

The evening is hailed as an entertaining success and Suzanne and Michael are on to planning the next party in March with a different theme and a new guest list.

Researching more game details, I found party kits range from $25 to $200+, depending on complexity and sophistication. Basic sets usually include invitation forms, name tags, scripts, and menu suggestions to fit the theme. Higher-end sets offer those options plus decorations, props, costumes, party souvenirs, and prizes.

Kits are tailored to different age groups from young children to teens to adults. Selections are mostly G-rated, without onstage violence.

Scripts can be similar to the Clue board game where victim, weapon, and murderer vary each time. Others feature set scripts that are not changeable.

If a murder dinner party is for profit where admission is charged or tickets are sold, a commercial license must be purchased (usually $200-250).

Variations offer options where all guests, even the host, can be suspects. For those, each person is assigned a number beforehand. At the beginning of the party, guests draw slips with corresponding numbers from a bowl. People are instructed to keep a straight face when they open slips. Most say “innocent” but one says “guilty.” Only the “guilty” player knows who they are.

Two scripts are provided to players—one to be followed if they’re innocent, a different one if they’re guilty.

Can you earn income by writing mystery party scripts? I found one site that accepts submissions but doesn’t mention compensation. Mastersofmystery.com‘s application outlines qualifications:

-

Exceptional storytelling skills with a passion for creating captivating narratives.

-

Strong writing and editing abilities, with a keen eye for detail.

-

Creativity and the ability to think critically to construct intricate murder mystery plots.

-

Excellent communication and collaboration skills to work effectively within a multidisciplinary team.

-

Previous experience in game writing, scriptwriting, or a related field is a plus.

I also found one successful business built around mystery party games. Dr. Bon Blossman is a physiologist with a passion for gaming, party planning, and writing. She combined all three into Mymysteryparty.com.

Blossman recalls:

“When I launched My Mystery Party in 2006, I handled everything—from game development and web design to customer service and shipping.”

The enterprise grew quickly. By 2009, Blossman was teaching as a post-doc and adjunct professor when realization hit her:

“My games and mystery novels had surpassed my academic income, leading me to become a full-time mystery party game developer and YA author.”

Her website showcases more than 100 games she’s written, with titles like the “Nancy Crew Mystery Series,” “Game of Crowns,” and “Twas the Night Before Murder.” The site includes videos, how-to articles, and an extensive storefront with related merchandise.

After almost 20 years in business, Blossman remains committed and hands-on:

“While I now have an amazing team assisting with party packs, phones, social media, and customer inquiries, I still develop every game and co-manage the websites, among other things.”

Her creativity, entrepreneurship, and hard work paid off.

“They say to turn your hobby into a career—and that’s exactly what I did!”

Encouraging words for all of us struggling authors.

During my interview with Suzanne, she mentioned, “I’d like to host an all-girl party,” for women who want to play the game, but their husbands resist.

That prompted an idea. Could I write the mystery dinner party script she wants? I’m always game (sorry) for a new challenge. Hmmm.

What if a guy who’d been married eight times is murdered and the ex-wives are all suspects…?

~~~

TKZers: Have you ever attended a mystery dinner party? Have you hosted one? To stretch writing muscles, would you try creating a script?

~~~

Looking for a cheap thrill? For a limited time, Deep Fake Double Down is on sale for only $.99.

Winner of the 2023 BookList Award for Best Mystery.

Sales link

Cassie Deakin investigates a forty-year-old murder mystery and comes face-to-face with a killer who will stop at nothing to keep his secret.

Cassie Deakin investigates a forty-year-old murder mystery and comes face-to-face with a killer who will stop at nothing to keep his secret.

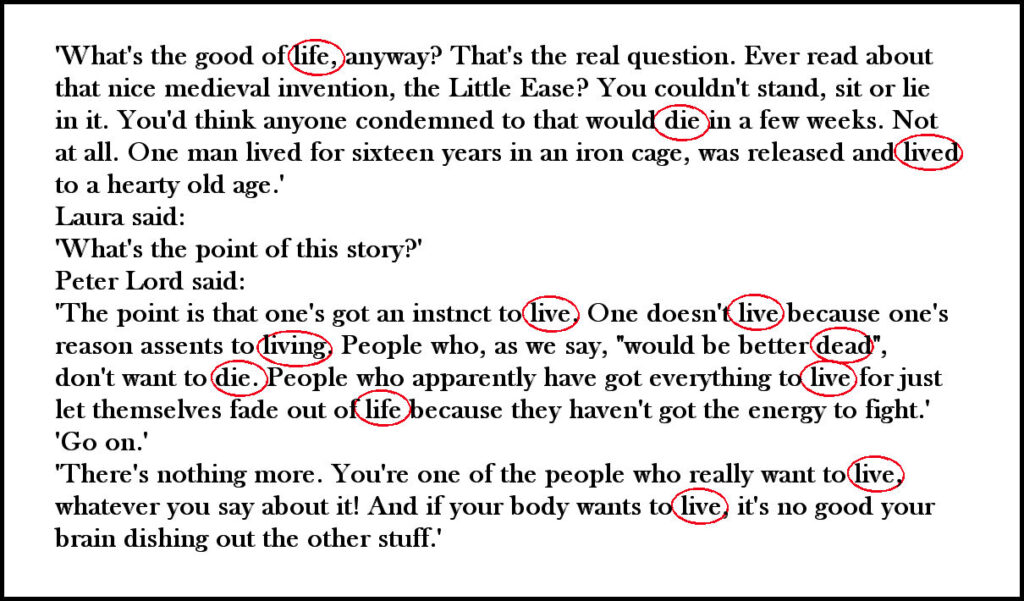

Dr. Danielsson plotted information about these aspects on a three-dimensional graph and plotted the same criteria from Arthur Conan Doyle’s works on the same graph. Christie’s books exhibited a consistency shown visually by her plotted points being clustered together while the points of Doyle’s stories were spread farther apart indicating his works were more dissimilar when compared to each other. This indicated that Doyle’s style had changed through the years while Christie’s had remained remarkably consistent.

Dr. Danielsson plotted information about these aspects on a three-dimensional graph and plotted the same criteria from Arthur Conan Doyle’s works on the same graph. Christie’s books exhibited a consistency shown visually by her plotted points being clustered together while the points of Doyle’s stories were spread farther apart indicating his works were more dissimilar when compared to each other. This indicated that Doyle’s style had changed through the years while Christie’s had remained remarkably consistent.

While some famous characters appear in multiple books and are popular with the reading public (e.g., Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, Captain Hastings), the number of characters in each novel may be just as important. This prompted an interesting theory by David Shephard, Master trainer in Neuro-Linguistic Programming.

While some famous characters appear in multiple books and are popular with the reading public (e.g., Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, Captain Hastings), the number of characters in each novel may be just as important. This prompted an interesting theory by David Shephard, Master trainer in Neuro-Linguistic Programming.

Although I found a site with the

Although I found a site with the

“Very few of us are what we seem.” –Agatha Christie

“Very few of us are what we seem.” –Agatha Christie