“If you want to change the world, pick up your pen and write.” ― Martin Luther

* * *

Every now and then we talk about why we feel compelled to write. I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, and it occurs to me that our motivation for writing may change as we grow in experience.

For example, the reason I decided to write my first novel wasn’t because I wanted to change the world or as some kind of personal catharsis. It was because I was listening to an audiobook while out running one day, and I thought I could write a mystery that was better than the one I was listening to. (A monumental act of hubris.)

When I returned home from my run, I got out my laptop and started typing. It was like being in a canoe, carried down the river by a current so strong, there was no use to fight it, even if I’d wanted to.

But as I got further into the story, I found there were things I wanted to say—about the world, society, myself—that changed my view of why I was doing this. By the time the book was published, I had arrived at a whole new perspective and a new “why” of writing.

* * *

So why do most writers write? Is there one overriding reason? Famous authors have offered their own opinions on this subject. As I read through some of their motivation for writing, I found themes of suffering, love, self-satisfaction, societal problems and more. Here are a few quotes:

“Any writer worth his salt writes to please himself…It’s a self-exploratory operation that is endless. An exorcism of not necessarily his demon, but of his divine discontent.” – Harper Lee

“When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art.’ I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing.” – George Orwell

“All that I hope to say in books, all that I ever hope to say, is that I love the world.” ― E.B. White

“I don’t know why I started writing. I don’t know why anybody does it. Maybe they’re bored, or failures at something else.” – Cormac McCarthy

“I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.” – Flannery O’Connor

“I believe there is hope for us all, even amid the suffering – and maybe even inside the suffering. And that’s why I write fiction, probably. It’s my attempt to keep that fragile strand of radical hope, to build a fire in the darkness.” – John Green

“That’s why I write, because life never works except in retrospect. You can’t control life, at least you can control your version.” – Chuck Palahniuk

“I write for those that have no voice, for the silent ones who’ve been damaged beyond repair; I write for the broken child within me…”

― Nitya Prakash

“I write because I love writing. I think I became a writer in order to explore my ideas and responses to the world around me, which I often found it difficult to share with others. Also I liked my autonomy, and a writer can choose his or her own working hours – midnight to dawn or whenever.” – Alex Miller

* * *

But you don’t have to be famous to have a gripping reason to write a book. A few weeks ago, my husband and I hosted a local author event for the community we live in. I had asked each of the ten published authors to send me a statement about why they write. Take a look.

As a former ICU nurse and family caregiver, I want to bring God’s hope to anyone facing a health crisis. —Tracy Crump

“I love teaching and encouraging young children. What better way than through story telling! In my barnyard adventures, I teach values and character building in relatable situations. I love how it gives parents a way to spend time with their child while learning values.” —Becky Thomas

“My stories are tales of trials and victory against impossible odds, carrying the message of enduring hope—because fantasy teaches us that with courage and resilience, we can persevere through the most extraordinary things.” —Beth Alvarez

“I created a coloring book to help kids and kids-at-heart relax and take some quiet time to bring color into their lives. We should live life in every color!” —Annette Teepe

“I write because I want to reach out to young readers who may currently have no spiritual interests that they might discover the difference Jesus can make in their lives and consider following Him.” —Larry Fitzgerald

“I write for the Lord, Kay, Arthur, myself, decency, and to add a drop to the sea of literature.” —Frank DiBianca

“My five mystery novels are set primarily in the historic Memphis area during the post war 1940s. They include action, some gun play, humor and even a little romance now and then.” —Nick Nixon

“Countless books have been written about every Beatles song ever recorded, but I really wanted to read a book about all the hits they had as solo artists. Since that book didn’t exist, I decided to write it.” —Gary Fearon

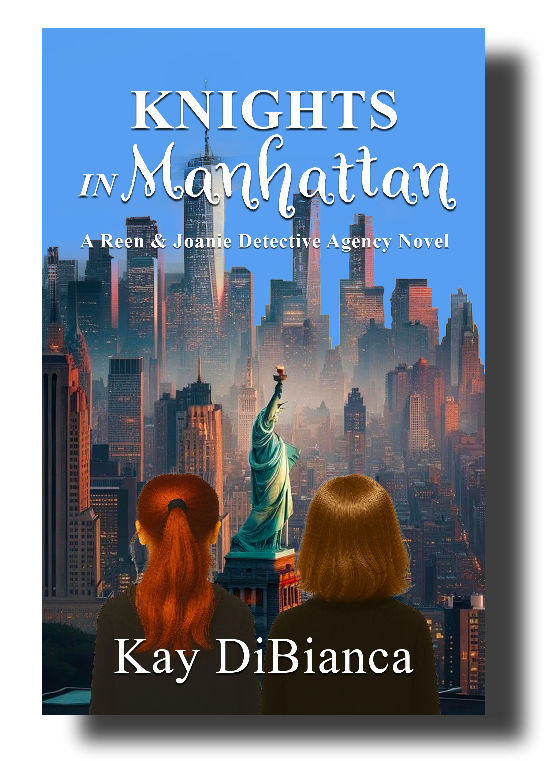

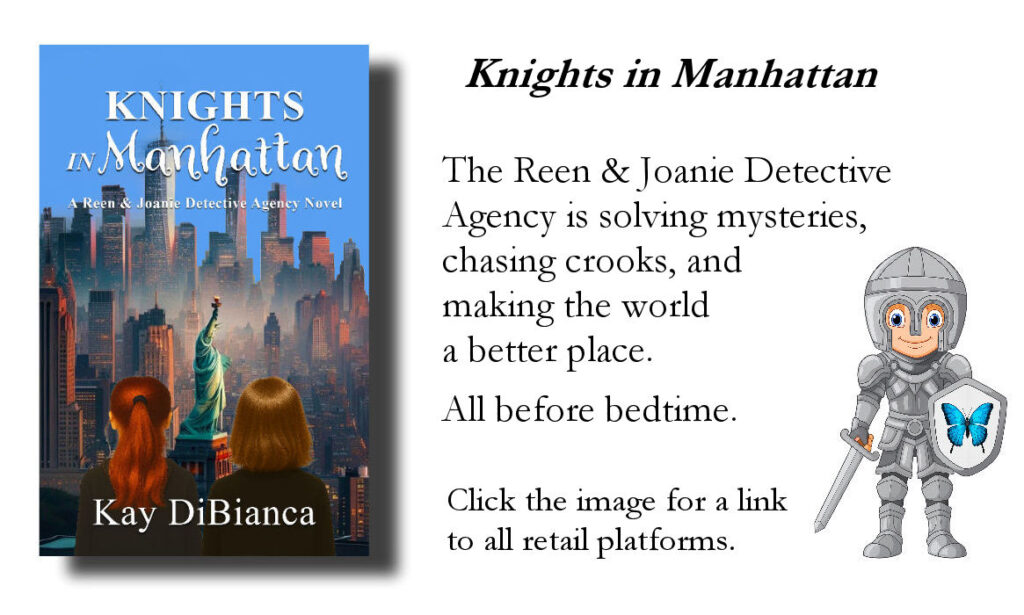

“I write mysteries because they reflect what I believe—that truth is worth pursuing, and that critical thinking, perseverance, and faith will lead us there.” —Kay DiBianca

* * *

So TKZers: Why do you write? And more specifically, why are you writing the current book you’re working on? Or any book in your backlist. Has your reason for writing changed over time?

Only a single star could reveal the truth buried beneath decades of lies. And only one woman had the courage to follow its light.

Click the image to go to the Amazon book detail page.

You’ll never find a better sparring partner than adversity. —Golda Meir

You’ll never find a better sparring partner than adversity. —Golda Meir