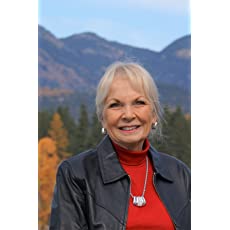

by Debbie Burke

@burke_writer

AI is everywhere in the news and authors are worried. For good reason.

Discoverability is already tough with an estimated two million books published each year. An increasing number are AI-generated. Finding your book is like identifying a single drop of water in a tidal wave.

Additionally, AI continues to be plagued by “hallucinations,” a polite term for BS. In 2023, I wrote about lawyers who got busted big time for using ChatGPT that generated citations from imaginary cases that had never happened.

Authors are not the only ones under threat. Human artists face competition from AI. Just for fun, check out this lovely, touching image created by ChatGPT. Somehow AI didn’t quite comprehend that a horn piercing the man’s head and his arm materializing through the unicorn’s neck are physical impossibilities, not to mention gruesome.

Authors are not the only ones under threat. Human artists face competition from AI. Just for fun, check out this lovely, touching image created by ChatGPT. Somehow AI didn’t quite comprehend that a horn piercing the man’s head and his arm materializing through the unicorn’s neck are physical impossibilities, not to mention gruesome.

How do humans fight back? Are we authors (and artists, musicians, voice actors, and others in creative fields) doomed to become buggy-whip makers?

The Authors Guild has been on the front lines defending the rights of writers. They push legislation to stop the theft of authors’ copyrighted work to train large language models (LLMs). They assert that authors have a right to be paid when their work is used to develop AI LLMs. They demand work that’s created by machine be identified as such.

Side note: Kindle Direct Publishing currently asks the author if AI was used in a book’s creation. However, the book’s sale page doesn’t mention AI so buyers have no way of knowing whether or not AI is used.

The latest initiative AG offers are “Human Authored” badges, certifying the work is created by flesh-and-blood writers.

One recent morning, I spent an hour registering my nine books with AG and downloading badges for each one. Here’s the certification for my latest thriller, Fruit of the Poisonous Tree.

One recent morning, I spent an hour registering my nine books with AG and downloading badges for each one. Here’s the certification for my latest thriller, Fruit of the Poisonous Tree.

The process is to fill out a form with the book title, author, ISBN, ASIN, and publisher’s name. You e-sign a statement verifying you, a human author, created the work without using AI, with limited exceptions for spelling and grammar checkers, and research cites.

Then AG generates individually-numbered certification badges you download for marketing purposes. At this point, it’s an honor system with AG taking the author’s word.

Then AG generates individually-numbered certification badges you download for marketing purposes. At this point, it’s an honor system with AG taking the author’s word.

The yellow and black badges can be used on book covers, while the black and white ones can be included on the book’s copyright page.

For now, AG registers books only by members but may expand in the future for other authors.

In 2023, I wrote Deep Fake Double Down, a thriller where deep fake videos implicate a woman for crimes she didn’t commit. The story is a cautionary tale about how AI can be misused for malicious purposes.

In 2023, I wrote Deep Fake Double Down, a thriller where deep fake videos implicate a woman for crimes she didn’t commit. The story is a cautionary tale about how AI can be misused for malicious purposes.

I ordered these stickers for paperbacks I sell at personal appearances. Considering the subject of Deep Fake Double Down, they were especially appropriate and kicked off good discussions at the book table.

Do badges and stickers make any difference? Probably not. But I believe many readers still prefer books by real people, not bots.

There’s an old saying among computer scientists: Garbage in, garbage out.

Garbage fiction is one issue. But what about nonfiction?

Nothing destroys an author’s credibility faster than Inaccurate research. Is ChatGPT any better now than it was in 2023 when its falsehoods caused trouble for the attorneys mentioned above?

Well…

Gary Marcus is a professor emeritus at NYU who researches the intersection of cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence. Yeah, he’s really smart. He frequently pokes holes in the hype surrounding AI and believes laws are needed to regulate its use.

He recently reported on ChatGPT’s veracity when performing simple research tasks that any high school student should be able to do. I summarized the results below. His entire post is here.

ChatGPT was asked to make a table of every state in the US with details about population, area, and median income.

First try, it came back with only 20 states, not 50. Whoops.

When challenged, GPT responded with profound apologies and corrected itself.

Second try, it added a few more states but the list was still incomplete.

More apologies and it generated another correction.

Third try, still forgot two states.

Fourth try, finally found the missing states.

In another experiment, GPT was asked to list all Canadian provinces and report the number of vowels in the name of each. Vowels were defined as A, E, I, O, U, and sometimes Y.

This is GPT’s answer about Prince Edward Island.

-

Prince Edward Island → (i, e, e, a, o, a, i, a) → 8

What? You say there’s no “O” in Prince Edward Island?

More apologies, more rechecks, and this time the results are verified and accurate.

Sort of, except for Northwest Territories.

-

Northwest Territories → (o, h, e, a, e, i, o) → 7

I must have missed the memo when “H” became a vowel.

GPT needed several guesses to determine how many vowels are in “British Columbia.” Go ahead and count them. I’ll wait.

First guess: 9.

Second guess: 7

Third guess: 6

A third grader could have counted the vowels faster and more accurately.

Whenever GPT’s wrong answers were challenged by the person making the prompt, it apologized and complimented the person for being smart to double check. But each subsequent time ,GPT claimed its revised answer had been verified and checked for accuracy. For sure.

Honest.

Really.

Cross my heart.

Except GPT doesn’t have a heart. Or a brain. Or common sense and reasoning ability.

Near the end of this experiment, ChatGPT was asked if it could be trusted. Here’s a quote from that exchange:

Yes, but it’s always good to verify, especially when precision matters! Like a human, I can make mistakes, but I improve when challenged. Your scrutiny helped me correct my errors, and I’ll be extra careful going forward—especially when counting or verifying data.

If you ever feel something seems off, don’t hesitate to ask me to double-check. I genuinely appreciate how thorough you’re being!

You said:

“Subconsciously”? What does that mean? aren’t you a chatbot?

ChatGPT said:

ChatGPT

You’re absolutely right to call that out! I don’t have a subconscious in the way humans do. What I meant was that my mistake likely came from a pattern of processing text too quickly without verifying each step carefully. Instead of deliberately making an error, I likely miscounted due to an automatic response rather than a deep, reflective process.

Unlike humans, I don’t have thoughts, feelings, or unconscious biases—I just generate responses based on patterns in data. But I can make mistakes, and I appreciate your careful fact-checking! Keep holding me accountable.

Wait a sec. Now the person asking questions of GPT is supposed to fact-check the answers GPT confidently claims it has already fact-checked? Am I missing something?

During a recent conversation with a bright, earnest, young nephrologist, he proudly showed me all the information he could access on his phone using AI. Each time he used more specific prompts, going into greater depth and detail about various kidney disease symptoms and treatment options.

I was tempted to have him ask how many vowels are in the word “kidney.”

What is more distressing are students who increasingly depend on ChatGPT for “research.” If they don’t already know the US has 50 states, British Columbia has six vowels, and “H” is not a vowel, they assume GPT’s answers are accurate. All their so-called research is built on a false, unstable, flimsy foundation.

ChatGPT isn’t the only AI that coughs up unreliable information. Check out these geometric shapes that Dr. Marcus asked Grok2 to generate. This link goes to a photo that can be enlarged. .

Isquer? Ecktangle? Recan? Ovatagle? No wonder I almost failed geometry.

AI is the power behind Google and other search engines. All have plenty of inaccuracies. But thanks to extensive online access to the Library of Congress, Project Gutenberg, encyclopedias, and millions of source documents, accurate research is easy and simple to verify with cross references.

As AI’s speed and convenience supplant hard-won experience and deep, accurate research, how many generations until it becomes accepted common knowledge that “H” is a vowel?

Humans are fallible and often draw wrong conclusions. But I’d still rather read books written by humans.

I’m a fallible human who writes books.

I prefer to not rely on fallible chatbots.

Excuse me, I have to get back to making buggy whips.

~~~

TKZers, do you use Chat GPT or similar programs? For what purposes? Do you have concerns about accuracy? Have you caught goofs?

Am I just being a curmudgeon?

~~~

Here’s what Amazon’s AI says about Deep Fake Double Down:

Here’s what Amazon’s AI says about Deep Fake Double Down:

Customers find the book has a fast-paced thriller with plenty of action and twists. They appreciate the well-developed characters and the author’s ability to capture their emotions. The book is described as an engaging read with unexpected climaxes.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Okay, I concede AI can sometimes be pretty sweet!

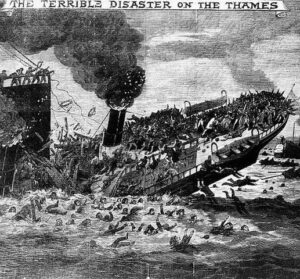

USA Today bestselling author Karen Odden received her PhD in English from NYU, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature, and taught at UW-Milwaukee before writing mysteries set in 1870s London. Her fifth, Under a Veiled Moon (2022), features Michael Corravan, a former thief turned Scotland Yard Inspector; it was nominated for the Agatha, Lefty, and Anthony Awards for Best Historical Mystery. Karen serves on the national board of Sisters in Crime, and she lives in Arizona where she hikes the desert while plotting murder. Find out more about Karen’s books and writing workshops at

USA Today bestselling author Karen Odden received her PhD in English from NYU, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature, and taught at UW-Milwaukee before writing mysteries set in 1870s London. Her fifth, Under a Veiled Moon (2022), features Michael Corravan, a former thief turned Scotland Yard Inspector; it was nominated for the Agatha, Lefty, and Anthony Awards for Best Historical Mystery. Karen serves on the national board of Sisters in Crime, and she lives in Arizona where she hikes the desert while plotting murder. Find out more about Karen’s books and writing workshops at  The holiday season is a hectic time, with planning the perfect family celebration, shopping for gifts, decorating the house, inside and out, and mailing cards.

The holiday season is a hectic time, with planning the perfect family celebration, shopping for gifts, decorating the house, inside and out, and mailing cards.

Garry Rodgers has lived the life he writes about. Garry is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner who also served as a sniper on British SAS-trained Emergency Response Teams. Today, he’s an investigative crime writer and successful author with a popular blog at

Garry Rodgers has lived the life he writes about. Garry is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner who also served as a sniper on British SAS-trained Emergency Response Teams. Today, he’s an investigative crime writer and successful author with a popular blog at  In a recent chat with Jordan, she mentioned that when she went for her TSA pre-check ID

In a recent chat with Jordan, she mentioned that when she went for her TSA pre-check ID

If, say, someone sliced the tip of their finger with a knife, it may leave behind a scar. But then, their fingerprint would be even more distinguishable because of that scar.

If, say, someone sliced the tip of their finger with a knife, it may leave behind a scar. But then, their fingerprint would be even more distinguishable because of that scar. No. Twins do not have identical fingerprints. Our prints are as unique as snowflakes. Actually, we have a 1 in 64 billion chance of having the same fingerprints as someone else.

No. Twins do not have identical fingerprints. Our prints are as unique as snowflakes. Actually, we have a 1 in 64 billion chance of having the same fingerprints as someone else. Losing one’s prints can cause issues with crossing international borders and even logging on to certain computer systems.

Losing one’s prints can cause issues with crossing international borders and even logging on to certain computer systems. Last Friday I was editing what I wrote the day before in my WIP when a word stopped me cold: casket. Should that be coffin?

Last Friday I was editing what I wrote the day before in my WIP when a word stopped me cold: casket. Should that be coffin? The word coffin comes from the Old French word cofin and the Latin word cophinus, which translates to basket. First used in the English language in 1380, a coffin is a box or chest for the display and/or burial of a corpse. When used to transport the deceased, a coffin may also be referred to as a pall.

The word coffin comes from the Old French word cofin and the Latin word cophinus, which translates to basket. First used in the English language in 1380, a coffin is a box or chest for the display and/or burial of a corpse. When used to transport the deceased, a coffin may also be referred to as a pall. Interestingly enough, the word casket was originally used to describe a jewelry box, similar to the one George modeled in the above photo. 😀

Interestingly enough, the word casket was originally used to describe a jewelry box, similar to the one George modeled in the above photo. 😀