By Debbie Burke

Recently I attended a Zoom workshop by bestselling historical mystery author Karen Odden. The opening slide of her PowerPoint presentation wowed us. It was a striking photo of an old-fashioned steam locomotive that had rammed through a wall on an upper floor of a building and was hanging down to the street below.

Karen Odden, historical mystery author

For the next 90 minutes, Karen kept us riveted with tales of actual catastrophes from Victorian England. Those events launched her down the research rabbit hole for her historical mystery series. Every discovery led to new story possibilities.

In addition to sharing her research adventures, Karen incorporated an advanced character-building workshop with fresh ideas I hadn’t run across before.

She kindly agreed to visit TKZ for an interview.

Welcome, Karen!

Debbie Burke: The inspiration process for your historical mystery series is a compelling study in itself. Would you walk us through that, including the turning points in the development? What was the moment of realization when you knew you had a winning concept?

Karen Odden: My fascination with the Victorian era began in grad school at NYU, in the 1990s, with a class called “The Dead Mother and Victorian Novels.” The professor noticed all these orphans running around Victorian novels – Jane Eyre, Pip, Oliver, Daniel Deronda, etc. She suggested the orphan was a trope for a profound historical change in England. Whereas in the 18th century, someone’s fortune and social status was inherited from their parents, in the 19th century, people (largely men) could make their own fortunes, in manufacturing, shipping, or whatever. So the orphan was a marker for how it was newly possible to define one’s self without reference to parents.

I found this way of thinking about literature and history fascinating, and I took more classes on Victorian literature, reading everything from Browning’s poems to Henry Morton Stanley’s African memoirs to Darwin’s scientific papers. I wrote my dissertation on the medical, legal, and popular literature written about Victorian railway disasters and the injuries they caused – with an eye to showing how those texts provided a framework for later theories, including shell shock and PTSD.

After graduating, I taught at UW-Milwaukee and did some free-lance editing. But around 2006, I decided I wanted to try writing a novel. For my topic, I leaned into my dissertation, putting a young woman and her laudanum-addicted mother on a railway train and sending it off the rails in 1874 London.

After many false starts, it was published, and I have remained in 1870s London for all my subsequent books. It’s a world I know, down to the shape of the ship rigging and the smells of tallow and lye, and although I have been told (more than once) that WWII books are an easier sell, I hope my books show the Victorian world in all its messy complexity, with all the possibilities for redemption.

DB: What is TDEC?

KO: TDEC is The Day Everything Changes. Basically, it’s the time when the main character’s equilibrium is thrown off, and (with few exceptions) it occurs in chapter one. For example, it’s the moment when Magwitch grabs Pip on the marsh, or Scarlett attends the ball that will devastate her as she finds out Ashley is engaged to Melanie. The reason TDEC is important is every character brings their own personal myth – what they have gleaned from their unique past experiences – to page 1, and that personal myth shapes the way they approach, perceive, and make meaning of every important experience that happens from TDEC on.

A funny story – when I was writing the book that became A LADY IN THE SMOKE (2016), TDEC is when Lady Elizabeth and her laudanum-addicted mother are in a railway crash. But I originally had it in chapter 8. (!) The first seven chapters were backstory about why Elizabeth and her mother didn’t get along and historical facts about railways, accidents, Victorian medical men, and so on. My free-lance editor told me I had to cut it. When I winced, she said it was fascinating; however, it needed to be in my head as I was writing, but not on the page, at least not like that. Much of the material in those 7 chapters is feathered in throughout the book, but the train wreck happens in chapter 1, as it should.

DB: One of your themes is PTSD, a psychiatric disorder that can be traced throughout history under different names. Could you talk about how you identified the condition in the past?

KO: One of the starting points for my dissertation was the account of Charles Dickens, who was in the Staplehurst, Kent railway crash in 1865.

Charles Dickens, Getty Images

He climbed out of his overturned carriage, helped his mistress Ellen Ternan and her mother out, and then began ministering to people. The railway company sent an express to bring passengers back to London, and Dickens went home to bed. But the next day he was so shaky he couldn’t sign his name. He developed ringing in his ears, nervous tremors, and terrible nightmares, dying five years to the day afterward.

Some of the medical men at the time called this “railway spine” — the theory being that all the shaking around passengers experienced inside the toppling carriage caused tiny lesions in the spinal matter, which resulted in symptoms across the whole body. Of course, these lesions were a complete fabrication — but under existing medical jurisprudence, people couldn’t obtain financial compensation for injuries that were only “nervous”; they had to be organic — literally, tied to an organ — and the spine counted.

I am persistently curious about what injuries and experiences “count” in our culture — and how they reach the tipping point of being worth discussing, litigating, researching, compensating, and curing. To my mind, the medical profession has failed us at certain times in history; and these failures can be devastating because the disavowal of injury lays on a whole second layer of trauma.

DB: You divide conflict into two categories: intrapersonal and interpersonal. Please explain the difference and how you use them in your fiction.

KO: For me, intrapersonal conflict occurs within a character and is usually the result of a conflict between an MC’s personal myth – the beliefs they have about the world and themselves, derived from past experiences – and their current lived experience. For example, in The Queen’s Gambit, chess prodigy Beth Harmon learned early on, in the orphanage, that mind-numbing drugs are an acceptable way to escape her world; but later, her lived experience shows that she loses chess tournaments when she plays hung over. So she must amend her personal myth, if she wants to achieve her desire of being chess champion. In parenting, sometimes this is called “natural consequences.”

Interpersonal conflict happens when two characters have personal myths that cannot be reconciled. In The Queen’s Gambit, Beth is a distrustful loner who doesn’t like to depend on others; but secondary character Benny Watts finds a sense of self-worth through teaching other people chess and being appreciated for his efforts. At the level of plot, Beth and Benny are in conflict because both want to be chess champions; at the level of character, they are in conflict because Beth’s personal myth includes the belief that gratitude is a sign of weakness, while for Benny other people’s gratitude contributes to his self-worth.

In my Inspector Corravan mysteries, Michael Corravan is a former thief, dock-worker, and bare-knuckles boxer who was orphaned as a youth and earned his place in his adoptive family by saving young Pat Doyle from a vicious beating. So Corravan comes out of Whitechapel scrappy, good with his fists, and with a belief that his value lies, in part, in his ability to rescue others. These are all fine traits for a Yard inspector.

But as his love interest Belinda points out, being a rescuer means Corravan never has to be vulnerable, and being vulnerable would make him a better listener and a better policeman. At first Corravan ridicules the idea, but when he finally allows himself to empathize with a powerless victim, the case breaks open. So there’s a combination of interpersonal and intrapersonal conflict that brings about a change in Corravan. He’s still a rescuer, but he understands the value of abandoning that role on occasion.

DB: Many writers fall into the bottomless well of historical research and can’t climb out to finish their story. How do you decide when you’ve done enough research and are ready to write the book?

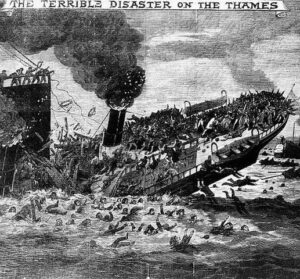

Thames Disaster, Getty Images

KO: Often I begin with a single, large nugget of Victorian history – for example, in UNDER A VEILED MOON, it was the Princess Alice steamship disaster of 1878, in which over 550 people drowned in the Thames. But after a few chapters of writing, I wanted to add complexity to what history says was a mere accident, so I read more and discovered that there was no passenger manifest because it was a pleasure steamer, like our hop-on-hop-off buses. No one had any idea who was on the boat!

I also read some articles about anti-Irish discrimination and thought it would be a good element to have the Irish Republican Brotherhood blamed initially, especially as Corrovan is Irish.

What I’ve noticed about myself is that as I reach somewhere around the half-way mark and know how my story is unfolding, I stop directed reading about the topic, but everything I read and hear incidentally becomes fodder. As I was finishing A TRACE OF DECEIT (about the theft and forgery of priceless paintings), I happened to read a New Yorker article that mentioned a piece of little-known English law that added a new, crazy twist. I try to stay flexible; when I find something intriguing that might fit into my book, I give it a try.

To some extent, setting all my books in 1870s London makes it easy. I have a repository of historical information about economics, laws, social mores, buildings, railways, injuries and illnesses, etc. So I don’t have to reinvent the world with each book. In fact, I’ve recycled several secondary characters, most notably Tom Flynn, the newspaperman for the (fictional) London Falcon.

DB: In How to Write a Mystery, Gayle Lynds wrote, “In the end, we novelists use perhaps a tenth of a percent of the research we’ve done for any one book.” What percentage actually makes it into your books? Do you have suggestions of what to do with leftover material?

KO: I would agree with that! Somewhere around 10-20 per cent. The key thing is to have it firmly in my head as I write — the way I know how to use a toaster, for example — so that historical information feathers in organically. I try to avoid info-dumps (unprocessed history plopped in) and what I call shoe-horning. Sometimes I want to stick in some cool historical factoid, and it just doesn’t fit. So I save it for a fun blogpost!

DB: Is there anything else you’d like to talk about that I haven’t asked?

KO: I’d just like to share that I’ve found it vitally important to develop a robust community of practice. Writing is often solitary; but my books are certainly better because of my beta-readers, and my writing life more joyful and productive (and successful) because of the librarians, booksellers, and other writing professionals I have met. No one told me this about being a writer – that I’d find a smart, generous community, which helps immensely as we all navigate the often challenging publishing industry.

~~~

Thank you, Karen, for sharing your fascinating journey with TKZ!

USA Today bestselling author Karen Odden received her PhD in English from NYU, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature, and taught at UW-Milwaukee before writing mysteries set in 1870s London. Her fifth, Under a Veiled Moon (2022), features Michael Corravan, a former thief turned Scotland Yard Inspector; it was nominated for the Agatha, Lefty, and Anthony Awards for Best Historical Mystery. Karen serves on the national board of Sisters in Crime, and she lives in Arizona where she hikes the desert while plotting murder. Find out more about Karen’s books and writing workshops at www.karenodden.com.

USA Today bestselling author Karen Odden received her PhD in English from NYU, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature, and taught at UW-Milwaukee before writing mysteries set in 1870s London. Her fifth, Under a Veiled Moon (2022), features Michael Corravan, a former thief turned Scotland Yard Inspector; it was nominated for the Agatha, Lefty, and Anthony Awards for Best Historical Mystery. Karen serves on the national board of Sisters in Crime, and she lives in Arizona where she hikes the desert while plotting murder. Find out more about Karen’s books and writing workshops at www.karenodden.com.

FB: @karenodden

twitter: @karen_odden

IG: @karen_m_odden

~~~

TKZers: Do you read and/or write historical fiction? What era interests you the most? What’s your favorite research trick?

Wonderful interview. I read both historical and contemporary fiction. Stories set in the 1800s are cool because it’s fascinating how people figured out things before modern conveniences. To research more recent history, like the 1940s-1970s, I like to watch old TV shows and movies.

Hi Vera, great point about modern conveniences. I took anesthetics and antibiotics for granted until I read about Civil War amputations to save soldiers from dying of gangrene.

I too love the shows and movies that reproduce old streets, clothes, and manners. I’m so excited that The Gilded Age is returning in October! Have you seen that one? My husband and I love it.

No, I haven’t seen The Gilded Age. Thanks for the rec!

Thanks for this interview. I always love to hear how other writers of historicals tackle their projects.

My favorite era will always be 19th century America, particularly the development of the west. Though right now I’m dipping my toes into America circa WWI (not writing ABOUT WWI but it has to be part of the societal backdrop because they are dealing with it). I can see why so many authors tend to stay in the same time period. The research investment is enormous.

I wouldn’t call it a research trick, but more an eccentricity of an info nerd 8-): I’ve recently (within the last year or so) signed up for a “this day in history” email which gives a list of a handful of happenings throughout history of the world on that given date.

I find it fascinating to compile these in a spreadsheet and look at all the given things on a particular day/month. It helps give you perspective as a person at all the different things happening in the world. For example, if you just take 2 things from January, 1905–on the one hand you have a bloody battle in WWI Russia, and on the other you have the world’s largest diamond being found in South Africa.

That at-a-glance look at history gives you a bird’s eye view of a particular time and can also lend itself to generating story ideas.

Brenda, thanks for adding the terrific tip about “this day in history”.

I LOVE my morning “This Day in History” email! They include quite a bit of Victorian England stuff — and I’ve found some great research tidbits through it and get ideas for blogposts. And I too love seeing the across-the-world approach … it reminds me of the Newseum, a museum in DC that closed (a sad thing, as it was one of the best ones, I thought, and so important for our age). Did you ever go? It was a museum all about the power of the news, and as you approached, on the walls outside, were perhaps 12 glass cases with that day’s front page of a newspaper in it — from a small town in Idaho to Paris to Australia to a town in Florida … the point being that no two headlines were alike. It reminded us of how provincial we all are (not a bad thing, just a good thing to remember). Anyway, thanks for commenting, and I am reading the TDIH emails right along with you. 🙂

Pingback: Interview with Karen Odden, Historical Mystery Author – Fix Yourself

Thanks, Debbie and Karen, for a very interesting post.

I don’t write historical fiction, and I have no research tricks to offer. I have begun exploring the mystery genre, and this post has sparked an interest in focusing on the industrial revolution. I look forward to exploring your books, Karen.

There’s a new project for you, Steve, cuz you always need more! 😉

Thanks, Steve! Another writer friend pointed out recently that research is necessary for all writing — even contemporary fiction — because of course even if we’re writing in the present day, we only occupy our little slice of the world. I’m fascinated by the research question — how much, what kind, and how do you use it. I hope you enjoy your exploration into the mystery genre, and I’d love to hear what you think, if you read one of my books. Cheers!

Fantastic interview! Thank you, Debbie and Karen. Karen’s books are definitely going on my to read list.

As I reader, I’ve enjoyed historical mysteries set in ancient Rome, medieval Europe and the Victorian period. I’d be hard pressed to pick a favorite. The 19th century certainly appeals to me, but so does the early and mid 20th century as we pull further away.

There’s been debate among my own beta readers regarding whether my 1980s library cozy mystery series is historical or not, given the proximity in time to our own (obviously getting further with each passing year). “A Shush Before Dying” takes place in April 1985. I cheat a bit with research because I was a young adult then, in college, and in fact, was hired at the library two and a half years later, so much of this is drawn on personal experience.

However, I do research things like zoning laws in the 1980s, local Victorian era homes, and have several fashion books, including a wonderful one based on the Sears catalog of the mid-1980s that help me set the tone. I’ve also watched and rewatched a number of films made in the 1980s. It’s Hollywood reality, but it can still help, and serve as a contrast with my own experience. Since my Meg Booker Librarian Mysteries is cozy, the focus is primarily on the community, rather than larger events, though the late Cold War will come into play at some point, for instance.

I have an idea for another series, more historical set Portland and/or Seattle of the 1950s, but that’s waiting in the wings.

Karen, thanks so much for being here today. Debbie, thanks for hosting her.

Dale, I used to think of history as events that happened before my time. Now I am history!

Thanks so much for the comment! And yes – things like Sears catalogs can often provide exactly the sort of everyday information that can be missing from scholarly books. Real people, real life. I need to look up your cozy series!

Debbie, thank you for inviting Karen. And Karen, thanks for the captivating interview. I had not heard that story about Charles Dickens. Fascinating.

I don’t normally choose historical fiction, but that genre occasionally comes up in my book club. Two that we’ve read are

Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks

The Personal Librarian by Marie Benedict and Victoria Murray

Question for Karen: In my limited experience with historical fiction, I’ve noticed there are two categories. 1) Stories that are written about a specific event or time in history but where the characters are clearly fictional, and 2) Stories that are written about historical figures that may contain lots of personal information that may or may not be factual.

Which category do your books fit in? I’m looking forward to reading one of them.

Kay, I also didn’t know about Dickens’s experience. Time to check out his later writing and see if/how the trauma affected it.

My book club just finished Year of Wonders, and we’ll be discussing it Thursday. I’m curious to see what the others in the group thought of it.

This is a great question, Kay! (And by the way, YEAR OF WONDERS is in my top 20 books of all time. I reread it every couple of years because I think it’s a primer on how to write solid historical fiction, from the perspective of an “average person” with an extraordinary voice.)

I’d say I’m a mix between 1 and 2. The Princess Alice disaster was real … and the incredible discrimination the Irish faced was real, but history tells us that the disaster was an accident, not sabotage (my fictional twist). And Sir C.E. Howard Vincent (Corravan’s superior at the Yard) was a real person, just as I represent him — a second son of a baronet, a reporter for the Daily Mail, who presented a report to Parliament about how he’d clean up the Yard. Corravan is fictional but based on two detective inspectors I read about in Haia Shpayer Makov’s fantastic book about detectives. And Belinda Gale is a composite of three Victorian women authors whom I researched for my dissertation years ago. So I sort of ride the line, I guess.

I hope you enjoy my books – just fyi, the first three are all stand-alones, featuring a different young woman protagonist in 1870s London, who is drawn into a mystery because someone she loves is injured or murdered. (Influenced by my childhood reading of Mary Stewart, Victoria Holt, Phyllis Whitney, that ilk.) My first, A LADY IN THE SMOKE, is about a young woman who experiences a railway crash (based on the Staplehurst one that Dickens was in). If you like art at all, you might try A TRACE OF DECEIT. But if you want something a little darker, about a Scotland Yard inspector who comes out of seedy Whitechapel, DOWN A DARK RIVER is the first book and UNDER A VEILED MOON is the second. I’ve been told, though, that you can read UAVM without having read DADR. If you read any, I’d love to hear what you think of them.

Thanks again for commenting!

Karen, Thank you for your reply. I also thought Year of Wonders was remarkably well-written. The only issue I had with it was the depiction of the rector, Michael Mompellion. He was clearly based on the real rector, William Mompesson, but Brooks makes Mompellion’s character strange, even sadistic at times, which I thought was unfair to the historical figure.

Down a Dark River sounds like a good place to start with your writing. I have it on my reading list! Thanks.

Wow, Debbie and Karen, wonderful interview…thoroughly enjoyed it.

I like stories set in the WW2 era, particularly if it includes intelligence activities-spy stuff. Ken Follett is one of my favorite authors.

I’ve published one contemporary novel, and I’m about to publish my second (October 1), which is also contemporary.

But, I have a fledgling project started. The setting is 1st century Middle East, just prior to the sack and burning of Rome. The MC is a young woman who travels to Rome at exactly the wrong time; or exactly the right time, depending upon your perspective. She becomes embroiled with the spies of the times, Jewish zealots and Nero’s minders.

So, as you can imagine, I’m doing a deep-dive into those times. It’s fascinating. And I’m reading some novels written in the same setting.

Thank you Debbie, for inviting Karen, and thank you, Karen, for opening the door so we can take a peek! 🙂

Wow, Deb, that’s an ambitious project and sounds fascinating. Best of luck with your research.

Wow, Deb, that sounds like a great project! For a while it seemed like hist fic (and historical mystery) was really dominated by WWII — and in some ways it still is. But with a few recent books about ancient periods/Greek myths, etc., people seem more open to reading about older eras. Good luck and have fun researching! Thanks for checking in and commenting. 🙂

I used to read the This Day In History in my newspaper (what’s that?) until too many of the historical facts actually happened in my lifetime and I remembered them.

Historical fiction is my normal go-to, but reading the interview makes me want to read Karen’s books!

Drat it! I wish we had an edit button! I don’t normally read historical fiction…that’s probably going to change now.

Patricia, you bring up another reason that I miss a newspaper with my morning coffee.

Well, if you do decide to venture into reading one of my historical fiction/mysteries, I’d love to hear what you think! 🙂 (If you want to know a bit more about the five books, I put a note above about how the first three books differ from the last two.) And I DO still read the NYT Sunday in the paper version. I also prefer books to kindle. There’s just something nice about having real coffee and a real paper on Sunday morning!

A fascinating interview, full of the good stuff that writers care about.

❖ Do you read and/or write historical fiction?

❦ [Spoiler alert!!] I’ve written a WWII thriller with loads of historical content. I’ve read quite a bit of such fiction and enjoy it. There’s a plot-relevant IRL locked room mystery in the book. Der Fuehrer did it, you’ll not be surprised to learn. The Munich Police still have the case on their books as a suicide, but my detective, Carl Jung, solves it.

❖ What era interests you the most?

❦ WWII, though the Victorian era also resonates. My best friend, Dave, was a radioman at Station Victor, the OSS base in England. I needed to know Genl. Donovan’s height for a meeting in my novel. “How tall was Genl. Donovan?” I asked. “Five foot eight,” he told me without hesitating. [Donovan had the men in formation and decided to show some judo throws. He asked for a “volunteer,” and pointed at Dave, who was his exact height. Dave met the pavement three times in less than a minute.]

❖ What’s your favorite research trick?

❦ Realizing that the research will never be complete, and accepting the fact that someone, somewhere, will see I’ve blundered over a small detail, no matter how much research I do. To forestall a bit of this, I added an appendix explaining several instances where my book deviates from known fact. E.g., Carl Jung did not go to Germany to analyze Hitler. Probably. And the OSS office in Bern, with its secret entrance, was not set up until later in 1942.

Fun fact: Jung was actually OSS agent #488.

J, what an interesting tidbit about your friend and Wild Bill Donovan. Thanks for adding your fascinating research.

Yes – I do use my author’s note (akin to your appendix) as my get-out-of-jail-free card. I try to share what’s truth, what’s fiction. Sometimes I move churches from one place to another in London. Other times I have my characters doing things that feel like they might not be Victorian (but are) — like drinking coffee, and I explain that yes, people did drink coffee, even if most times on TV it seems they only drink tea (and tea was the more popular beverage).

I love your idea that research is never done. I totally agree!

It seems like your books may have some of what mine do — a mix of real people and events mixed with fiction. Thank you for sharing!

Thanks for telling us about the orphan theme in Victorian novels. I’m also fascinated by that period, and think there are many similarities between Victorian poverty and today’s underprivileged.

Thanks, Debbie, for introducing me to this amazing author.

Elaine, I was delighted to meet Karen and discover her techniques for bringing the past to vivid life.

Thanks for stopping by! One reason I love the Victorian era is the number of similarities with our own — they had hundreds of newspapers, which would often reprint things from each other. (Social Media.) There was rampant discrimination. There were people who could only think in terms of binaries (Us/Them, Whig/Tory, etc.) There were anxieties about foreigners, and new technologies. The list goes on and on. And I love exploring our own world vis-a-vis the Victorians, at a distance, as it were, without what Jill Lepore recently called “the leaden passions of our present.” Thanks for stopping by and commenting!

Fabulous interview, ladies! Karen, I’m impressed that you’ve stayed in your chosen era rather than bend to WWII like many others. Way to stay true to who you are!

Let’s hear it for being true to oneself, Sue! You’re another good example of that.

Thanks!! Yes – I’ve been asked more than once, “Why don’t you write WWII?” It’s an easier sell … partly because (IMHO) it’s the last time the world was divided neatly along good/evil. This gives WWII tremendous narrative power, in that in a novel, you can disrupt that line and then reestablish it, which is very satisfying. But frankly, Victorian England didn’t have those kinds of binaries. It was messier … which is partly why I like it. Thank you for your encouraging words … I’ll keep writing my era 🙂

I’m currently reading The Victor Garden by Rhys Bowen (about halfway through) and I know Rhys does her homework, while making sure she’s telling a story, not giving a history lesson. Another author I’m trusting is Catriona McPherson. I was given a copy of A Deadly Measure of Brimstone at Left Coast Crime, and it rang true.

Disclaimer. I hated history classes, and am probably the best possible reader of historical fiction because I don’t know enough to question anything. Although I did stop and look up the use of “cold” when reading Year of Wonders because I wasn’t aware the term would have been used during the 1600s, but it was.

Terry, history in school for me was largely boring and emphasized memorization of dates rather than understanding the significance of events. A well-written, well-researched historical novel provides a much better education than the way we were taught.

I love both Rhys and Catriona’s books! One of the marks of a good novel, I think, is that the historical info is feathered in organically … not dumped in. Rhys and Catriona both do that well!

Thanks for sharing your secrets.

Welcome to the Zone, Kathleen. Lots of secrets around here and we love to share.