Finished the Draft. Now What?

Terry Odell

Since my last post, I reached “the end” of the current manuscript. Yippee! Of course, now the real “fun” begins. Editing. Previously, I’ve talked about how I attempt to fool my brain with printing the manuscript in columns and in a different font. You can find that post here. That’s what I’ll be doing for the next several weeks before sending it off to my editor.

One thing I’m super happy about is that I found a title. I know some authors can’t start writing without one. For me, it’s usually the last thing I come up with. I can think of only two exceptions. What’s In A Name? got its title when I was forced to fill out an entry sheet for a RWA chapter contest. There was this big, blank line that said “Title.” The title was almost a placeholder, but I realized that it actually fit the story. Subconscious at work? Maybe. Probably.

The other one was Starting Over which is exactly what I was doing. It wasn’t so much a name of the manuscript, but rather the name I gave the folder in my computer where I would be saving drafts, chapters, notes, etc. The title worked, for the book, too, as it turned out.

When rights reverted, indie publishing still wasn’t a thing, so I approached another publisher. They accepted it, but didn’t want the same title, so it became Nowhere to Hide, which I kept when rights from that publisher reverted to me.

What was I talking about? Right. The new book and its title. It’s part of my Mapleton Mystery series, and the pattern for titles throughout has been a two-word title, the first word being “Deadly.” You’d think coming up with one word would be easy. Ha! Not for me.

Since I had finished the draft, I had some idea of a theme (I don’t think of those when I start, either). It came to me. Deadly Ambitions. It worked, my writing buddy liked it, and my editor liked it.

That puts me one step closer to publication.

But first, I have to whip this draft into shape.

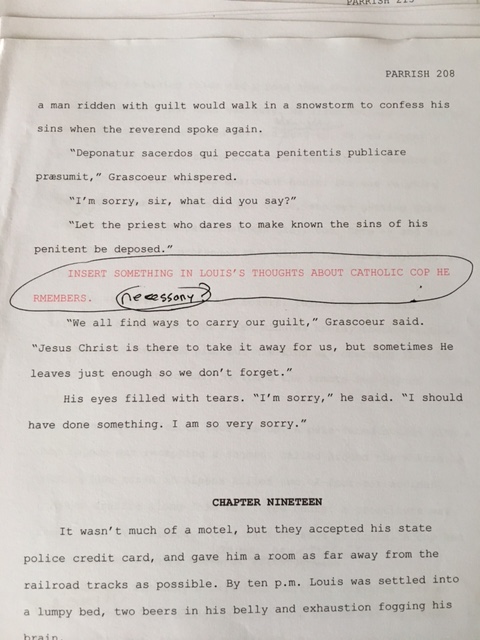

We talk about first pages a lot here at TKZ. They’re important. Very important. It’s been months since I’ve written my first chapter, and there were changes as there always are when I’m starting a new book. Am I starting in the wrong place? Am I info dumping? Will it entice new readers to keep going? (The current wip is the 9th novel, and the 12th work in my Mapleton mystery series.) I write them so they can be read as stand alones, but there’s always the temptation to make sure new readers don’t feel confused when I introduce recurring characters. I know that bugs the heck out of me, which is the main reason I prefer to start with book one in a series. JSB is always saying readers will wait for answers, but how long?

My Mapleton books are small town police procedurals. Sort of. I’ve had reviewers comment that there’s a “cozy feel” to them. But they definitely do not fit the rules/guidelines/expectations of a cozy.

When I’m reading, I like seeing the off-the-job side of my protagonist. Through the series, Gordon has dated, become engaged, married, and is now at the “newlywed phase is starting to wear off” point. Angie, his girlfriend-fiancé-wife has been with him in some capacity since book one.

My dilemma, as is frequently the case, is how much page time she gets, along with how much page time Daily Bread, the diner she runs, gets. Are readers going to want to skim those scenes to get back to the Cop Stuff and Chief Stuff Gordon has to deal with? In the current book, she’s playing a significant role and is personally involved in one of Gordon’s cases. (No spoilers.) She’s part of the opening scene, but is it too much? Not enough? I’ll pose that question to you, TKZers.

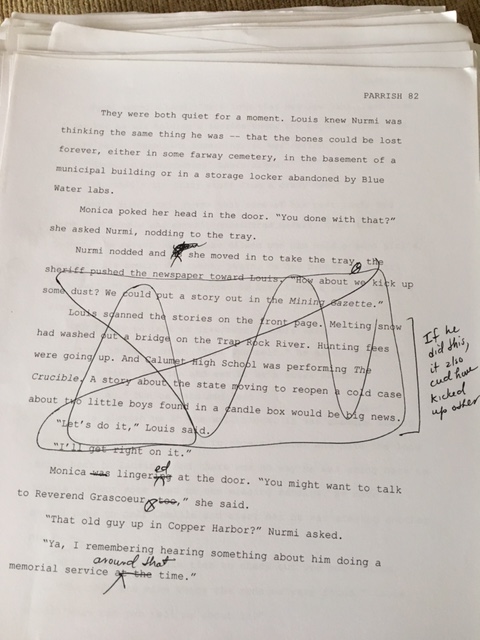

These were the opening paragraphs in my first draft.

Gordon Hepler, Mapleton, Colorado’s Chief of Police, moseyed over to Jerry Illingsworth, newly elected mayor of the city. This was Jerry’s night, and it was in full swing. The event room at the Community Center was filled with his supporters, all enjoying the food and drink.

Angie, his wife, was in charge of the food, and she’d done a great job, deviating from the usual fare at Daily Bread. Jerry had requested something more upscale, and she’d been happy to comply, especially since her restaurant was closed for remodeling. The extra work provided much needed income.

Gordon snagged a shrimp-topped canape—Angie’s term. Gordon called them nibbles—from a passing server. The group around Jerry wandered off, and Gordon moved in to congratulate the new mayor.

“Would it be inappropriate for me to say It’s about time?” Jerry gave a quiet laugh. “Three recounts before Nelson Manning accepted—reluctantly is too kind a word—defeat.”

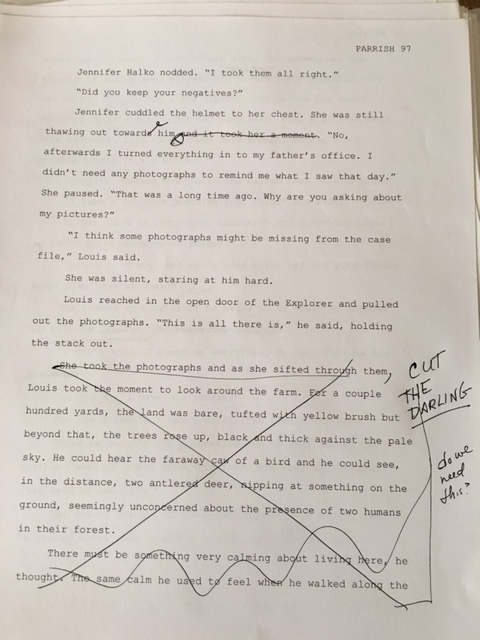

When I started my edits, I thought I’d devoted too much ‘dumping’ of who Angie was and her role, so I tightened it to this. (Only the second paragraph was changed.)

Gordon Hepler, Mapleton, Colorado’s Chief of Police, moseyed over to Jerry Illingsworth, newly elected mayor of the city. This was Jerry’s night, and it was in full swing. The event room at the Community Center was filled with his supporters, all enjoying the food and drink.

Gordon snagged a shrimp-topped canape—his wife Angie’s term—from a passing server. She was the chef, so she would know. Gordon called them nibbles. The group around Jerry wandered off, and Gordon moved in to congratulate the new mayor.

“Would it be inappropriate for me to say It’s about time?” Jerry gave a quiet laugh. “Three recounts before Nelson Manning accepted—reluctantly is too kind a word—defeat.”

What’s your take? Too much? Too little?

~~~~~

Oh, and for those of you who are interested in my images from our anniversary getaway last month, you can find them here.

Oh, and for those of you who are interested in my images from our anniversary getaway last month, you can find them here.

New! Find me at Substack with Writings and Wanderings

When breaking family ties is the only option.

Madison Westfield has information that could short-circuit her politician father’s campaign for governor. But he’s family. Although he was a father more in word than deed, she changes her identity and leaves the country rather than blow the whistle.

Blackthorne, Inc. taps Security and Investigations staffer, Logan Bolt, to track down Madison Westfield. When he finds her in the Faroe Islands, her story doesn’t match the one her father told Blackthorne. The investigation assignment quickly switches to personal protection for Madison.

Soon, they’re involved with a drug ring and a kidnapping attempt. Will working together put them in more danger? Can a budding relationship survive the dangers they encounter?

Like bang for your buck? I have a new Triple-D Ranch bundle. All four novels for one low price. One stop shopping here.

Like bang for your buck? I have a new Triple-D Ranch bundle. All four novels for one low price. One stop shopping here.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”