“I have rewritten — often several times — every word I have ever published. My pencils outlast their erasers.” –Vladimir Nabokov.

By PJ Parrish

This is it. This is the third draft. This is the last best chance to get it right.

I’m in rewrite hell this week. Actually, it’s not hell. To me, at least. I love this phase of the process because the really hard work is done — the laying of the foundation, the erecting of the beams, the finishing of the roof. Now I just have to go back in and make sure the structure is sturdy, the flow from room to room logical, and the style true to my own. Oh, and it would be great if someone gets so emotionally caught up that they maybe want to buy it.

Rewriting is where the book is truly made. No one will ever convince me otherwise. Yeah, my sister and I can turn out a pretty decent first draft, but who wants pretty decent these days? What reader would settle for it? What writer would? So I’m digging back into the coffee-stained third draft this week to up the ante as far as I can.

Now maybe you’re one of those rare birds who can produce a perfect book in a single swoop. (Like Lee Child who told one interviewer: “I don’t want to improve it. When I’ve written something, that is the way it has to stay.”). But most of us need to go back and reassess and rearrange. I always tell my workshop folks that the first draft is written with the heart, but the second, third…tenth, well, that’s written with the head.

Two quick tips: Wait as long as you can stand after you finish your first draft to start rewrites. You need a break from the beast that has consumed your life for eight months or eight years. Also, I always print out a manuscript for rewriting because the eye, so attuned to the screen, becomes inured to error and excess. Seeing your work in a physical state also gives it a gravitas that the computer can’t imitate. Here’s my big baby in three messy piles:

Now what I’d like to do is show you my draft’s innards. But before I drag out my sausage machine, let’s do a quick review of rewrite basics:

Structural Problems

This is a big issue, so be prepared to spend a lot of time and brain-power on it. You’re going to find plot holes to plug, characters to amplify, a muddy middle to amp up, conflicts to bring into higher relief. Oh yeah….and you might uncover that elusive theme. Ask yourself all the basic questions that our bloggers here post about: Is your three-act structure sound? Do your characters want something and is it important enough to drive their arcs? Is your central conflict tantalizing enough to support a whole novel? What, at its heart, is your book about? (not plot, but theme.).

Logic Lapses

Does your plot make sense and it is believable? (Those are two different things). Do you resort to a deus ex machina or the Long Lost Uncle From Australia villain reveal? Do your characters act in accordance with their natures or do you have them doing stupid illogical things? Are your police and forensics procedures sound or did you try to fake it? (ie clip and magazine are not the same). Does your research hold up? Is your fantasy, horror or alien world well-rendered and credible?

Confusion and Clarity Issues

Can the reader easily figure out what’s going on? This does not mean artful misdirection or red herrings. This means you choreograph movement and events carefully, everything from small stuff like moving people across a room or a country to big things like why did they did a certain thing (motivation). Do you make it clear where we are and what time period we’re in? Can the reader discern a mood or tone in your book (dark? hardboiled? humorous? sardonic?)

Flabby Writing

Have you ferreted out all the junk-writing? This includes overwrought and repetitious description, dumb physical moves (“He bent his left arm and brought the beer up to his lips.”…no, he took a drink.) Do you rely on adverbs instead of muscular dialogue? Have you pruned away all the unnecessary words you can, especially as you near the last third of the story when the reader wants to move faster?

Proof Reading

Spelling, grammar, punctuation…know them or hire an editor who does. Watch out for dumb inconsistencies like changing a character’s eye color or name spelling. Double check for errors (use Google maps to verify that it is, indeed, a four-hour drive from Moose Butt to Manitou). Did you get rid of all your brain farts? I once read a novel that described the crime as as grizzly murder. Shoot, in one of my first drafts, I had a distraught character balling like a girl…thank God for editors.

Okay, now let’s look at some of my mistakes and I’ll show you how I hope to run ’em back through the sausage-making machine:

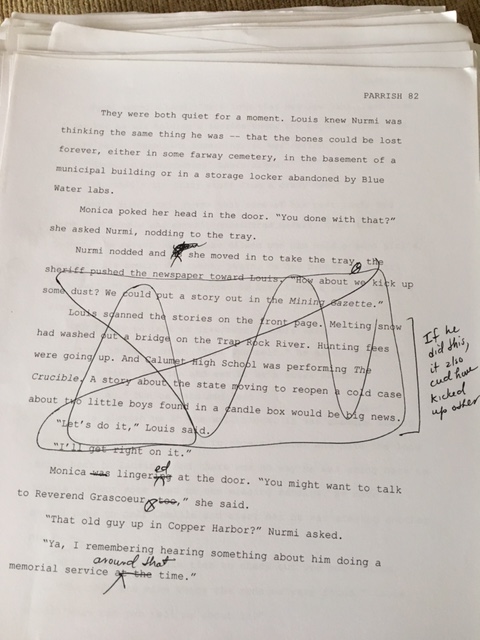

Here we are on page 1 and already I have a problem. In my first chapter (indeed, the whole book) I neglected to tell the reader what year we’re in. My series started in year 1981 and has progressed now to 1991. I have to make sure my readers know this early because the forensics, cell phones, computers are all going to be different. But notice that I DID find a way to tell readers we are in Lansing Michigan.  I have a logic/plot problem here. In the deleted part, the sheriff offers to plant a story about Louis’s case in the local paper, hoping to stir up leads. But if he does this, it will tip off a suspect who I have come forward fifteen chapters later — and it blows up the plot! This sounded good when I wrote it on pg 82 but it doesn’t hold up on page 345.

I have a logic/plot problem here. In the deleted part, the sheriff offers to plant a story about Louis’s case in the local paper, hoping to stir up leads. But if he does this, it will tip off a suspect who I have come forward fifteen chapters later — and it blows up the plot! This sounded good when I wrote it on pg 82 but it doesn’t hold up on page 345.

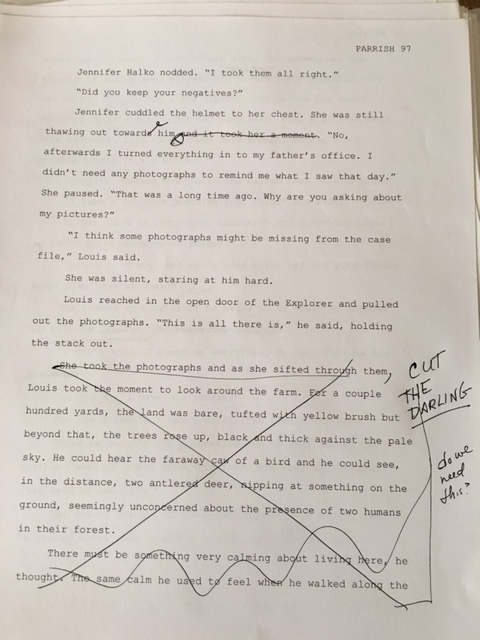

This one falls under Elmore Leonard’s Kill Your Darlings. Louis is about to uncover a major gruesome clue and plot point on next page. (Yay! Momentum!) Why in the world do I need him looking around this farm at deer or listening to crows? (Boo! Screeching halt!) It was a pretty image when I wrote it but adds nothing, especially since I had already described the lonely isolation of the place in vivid detail two pages ago.

Nice clean page, right? Except for one bone-headed mistake. One of my main characters is a teetotaler. It’s a big point in his make-up, which my hero Louis knows. So why does Louis set a beer at the man’s side? Always watch for dumb mistakes and inconsistencies. In film, a script supervisor oversees the continuity of a movie including wardrobe, props, set dressing, hair, makeup and the actions of the actors during a scene. You don’t have one of these backing you up. So be careful.

I call this one the Jacqueline Susann problem. The copy after the double space is the beginning of a seven-page scene where Louis goes to a state forensics lab to log in his evidence. It’s interesting in so much as it shows nerdy police procedure. But my book is running long so I have to MAKE DECISIONS about what to put “on camera” and what to recount in narrative. Now some scenes must be on camera (decisive action, great clue reveals) but some stuff can be dealt with efficiently in a character’s thoughts after the fact. I am going to cut this scene and in the following chapter just say “Louis went to the lab in Marquette and logged in the evidence.” Back to Jackie Susann: When she turned in one of her potboilers, she devoted an entire chapter to a Democratic National Convention (she had gone to one and was going to show off her research, damn it!). Her wise editor Michael Korda told her to cut it. She fought him but in the end the book said: “The convention was held.”

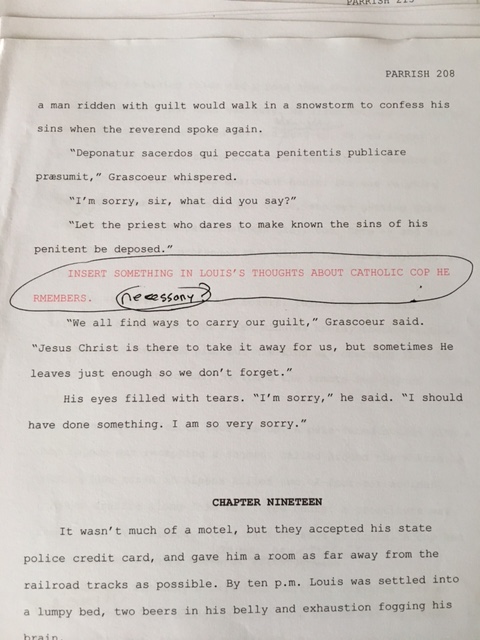

See the part in red? During first draft, I was trying to hone the theme (forgiving those who hurt you as a child) so I was acutely aware of all religious references I used. In this scene, Louis has interviewed an ex-priest who took confession from a murderer decades ago. The priest talks about the sanctity of the confessional but how his guilt eventually drove him from the Church. Catholic cops grapple hard with this issue. But after a powerful scene with the priest, do I really need Louis thinking about this? No, it was one theme-bridge too far. Lesson: Have a theme but don’t preach.

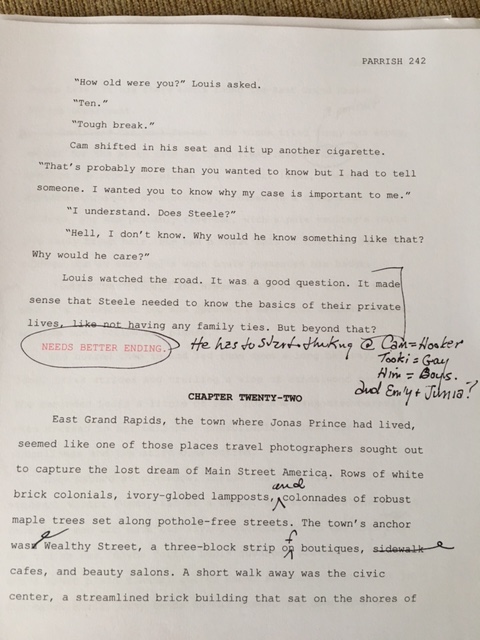

I am a perfectionist. It is hard for me to move on until I get a paragraph, a scene, a chapter right. I am trying hard to change this flaw. My sister flogs me constantly: JUST WRITE! So now I put notes to myself in red to fix it later. This is called faith. {{sigh}} Read the ending of this scene. It sucks, right? I know that. I will fix it. Lesson: Don’t get paralyzed by perfection. Move forward. Chances are excellent that by the time you finish the first draft you will know exactly how to make an early chapter end — or begin — with more punch and precision.

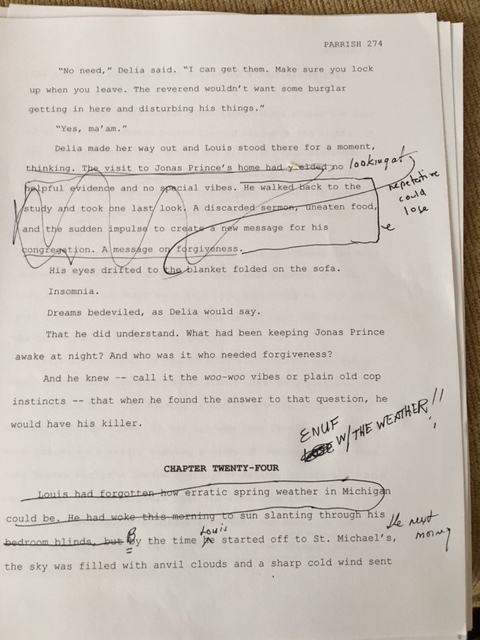

Look at the beginning of chapter 24. Argh! I opened it with weather. Now, that is okay except that it is April in Michigan and it is raining almost every day in my book. By page 274, the reader GETS that because I have told them at least four times. Lesson: Go easy on weather and don’t repeat the obvious.

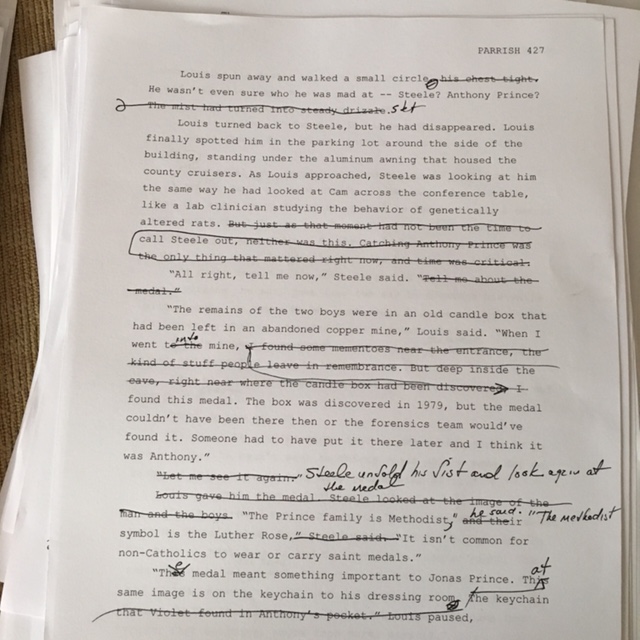

I included this page just to make the point about flabby writing. All the stuff I crossed out is fat. Always aim for economy, which is not the same as underwriting (a sin in its own right). When you are just moving characters around in time and space, do it with as few and unflashy words as possible. Almost half the pages in my manuscript are marked up like this.

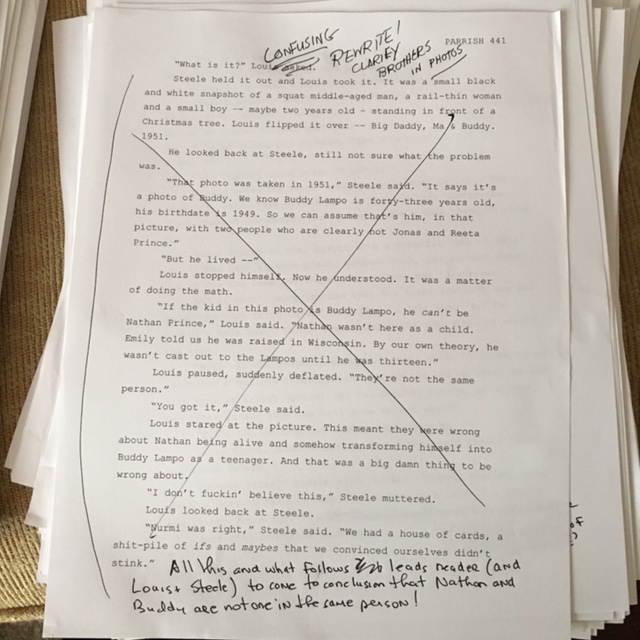

I saved the most important one for last. The sin isn’t apparent to you but boy, did it jump off the page when I read it in rewrites. We laid down a very complicated bread-crumb trail of clues in this book about mistaken identities, time-lines, family trees. So it was critical that as the book neared its climax, we explained this so the reader would understand how the puzzle finally fit together. Well, we didn’t do a good job of ‘splainin. As a major clue, we had two photographs of boys that we thought was a peachy misdirection but it only confused the reader in the end. It came on page 441 and was a major plot mistake that we had to acknowledge and correct. It was major surgery but without it, the book would have died. Lesson 1: Don’t avoid the hardest work. Lesson 2: Don’t confuse the reader. Especially at the end, after they have invested so much time and heart into your story. Make the ending clear, satisfying and logical. Your plot twists must be well-earned.

That’s it, crime dogs. Now if you’ll excuse me, I have work to do.

Good encouragement and illustration. This topic doesn’t get the attention that things like structure get, though it deserves attention. I think the illustrations help since this is not something that can be covered just by “theory” the way structure tends to be. For example, your deleted sections show that a correction is often needed not because the passage itself is bad but because of context.

The illustration pages also told me the story takes place in Michigan, which I still consider home.

Hope this helps a little Eric. I have always found it more useful to show instead of tell. As for Michigan…it’s my home state and this year I made a major life change, moving back there for half the year. We just left our little condo in Traverse City last week (major signal to go south: Dogs shivering on morning walk). It made me so happy to be home again. Now we’re back in Tallahassee for the winter. Just had the fireplace guy in to check out the gas line, even though it’s going to be 82 here today. 🙂 Believe it or not, it gets pretty chilly in Tally in winter.

If you’d rather winter in the U.P., my sister has a place for sale.

Interesting post. I love seeing your process. It’s vastly different from mine but your insights are spot on. I have a rolling edits process & don’t work in drafts, but your thoughts & instincts are very helpful to read.

To lessen the blow to “cut your darlings,” I create a CUTS FILE to cut & paste there. I file them away in case I need them later but I never do

Like you, I prefer the printed page to do edits. Lately I’ve added a final read through my ereader to make notes on typos. An error I’m finding in my work, as well as authors I read for pleasure, are the words I omit. Hard to catch if you don’t have the discipline to read aloud or read slowly & deliberately.

Hey Jordan,

Good name f or it — rolling edits. I do this as well but I try hard to limit the time I spend on it because I tend to obsess about stuff and not move forward. I am trying harder to work more toward a final rough draft process but I am not totally there yet. I still cant resist the urge to go back and pick nits.

I, too, kept a DEAD DARLINGS file. It’s called “Sh–t I Might Need.” I have never felt the need to go back and retrieve anything that is in it, which is probably why I used the expletive. 🙂

PJ, this post came at a good time (if re-write time is ever good), since I’m responding to the first pass of my editor through my next novel. Although I try hard to make her job obsolete, she’s pointed out a number of things that should be changed–some requiring a few explanatory sentences, others necessitating a total re-write of a scene or even a chapter. I hate writers who can churn out novels with no thought of (or need for) rewriting. Then again, I wish I were among that number.

Thanks for some very good advice.

Getting that first letter/email from your editor is never easy. You’re hoping that it will say, “Wow, this is great! No work required!” But if you’re lucky enough to have a good editor, you know there will be homework assignments. I wouldn’t sweat not being a writer who, as you say, can churn out novels with no need for rewriting. I’m suspicious of those folks. If you read further into the interview I cited with Lee Child, you find that he sweats out every word he puts on paper. Maybe his rewriting goes on all in his head before he commits anything by keyboard. It’s all just a difference, I think in how our brains work.

Like Jordan, I edit as I go, but don’t always fix things immediately. I also have to work from a hard copy, and I print out each scene as I finish the draft. That gives me a running start the next day.

Yet … sigh … when the manuscript is finished, it still needs the kind of run-through you’ve described here. And I wont’ say how many chapters end with “Needs a hook” on my first drafts. Or second. Often, simply backing up a paragraph or three can take care of much of that problem.

As always, thanks so much for sharing your process.

“Needs a hook.”

Been there, typed that. So important to find that juicy ending for each scene/chapter that is a compelling bridge to what comes next.

Kris, these pictures are each worth a 1000 words. As Eric says, it’s one thing to read the theories, but altogether different to see the actual strike-throughs, margin notes, and gaping holes where something should have been. So helpful!

Love the Adrienne Rich epigraph. Is that part of the book, or just a reminder to yourself?

Going to use the Rich poem as an epigraph. I’m continually amazed at the serendipity/synchronicity that goes into writing. I happened upon her poem by accident one day reading a story about her in a magazine, when I was well into writing this book. I had already chosen the title “The Damage Done” at that point, but the poem’s lines were perfect.

This was very helpful. Thank you for your real-life examples. It’s intimidating to a newbie like me, but breaking down the rewriting into chunks/categories helps. And thanks for a peek into your latest work!

Glad to help, Priscilla!

Actually seeing the process in your photos was much more helpful than just telling us about it (ha-where have I heard that before?) Thanks for letting it all hang out. Lately I’ve been reformatting my MS so it looks like it would in book form (5 1/2 x 8″page size, .75″ margins, Times Roman 10 point, 1.5 spacing) – for some reason, it looks totally different that way-like a reader would see it, and helps me with revision.

My sister has done that, too, Maggie…creating a “fake” book via formatting. It works really well for final proofing because as you say, it looks exactly like a real book, which makes your proofing eyes readjust again. Sometimes, I have printed this out to do editing.

Impressive blog, PJ. I appreciate the step by step process you’ve showed us. When I get to the final edit, I cut whole scenes and paragraphs and save that deathless prose in a special file — WHICH I NEVER USE. It feels like I’m opening a vein when I cut it out, but later it is pure fat — or a rant that would bore the reader.

There’s a part of me that still can’t stand the idea of cutting out those 7 pages, Elaine. I know they slow things down but the writing of that scene came so hard….

sigh.

Out it goes.

A wonderful, amazing post. So full of wisdom and generosity.

Good to see you here, Larry! Thanks.

Thanks for sharing this! As a reader, I love to see what authors go through to fine tune their “Babies”. Bravo!

Yeah, me to, Philip. You probably already know this, but Stephen King ends his On Writing book with a marked up version of a short story he did with all his remarks and cuts. I still love to go back and read it.

Great useable info PJ. I typically do a lot of rewrites once the draft is done. Usually 5 or 6 passes before it goes to my editor, then a pass after that before sending it to the publisher, who then runs it through a second editor and I get one more pass before it is out of my hands. Makes a ton of difference I think.

Late in life I’ve come to the idea that the more editors, the better. For my last book, I had two excellent line editors (only because one got promoted and moved on) and four copy editors. Each editor was good to excellent and each brought a unique talent to the process.

From my other perspective as an audiobook narrator, I will chime in as well.

I narrate a lot of books, including some whole series. Some, like Gilstrap’s and Bell’s, come to me in pretty good shape. Clear, concise writing, very few typos and no confusion. That makes books easy to narrate because I can get into the story and characters without getting derailed trying to figure out what the author is trying to say.

I’ve also narrated some series where in one case I could tell the writer was learning how to write. The first novels really needed to be redone a few times before they hit the market, whereas by the 10th novel three years later they were much improved and the story flowed considerably better. In another case the author apparently had a multi-book deal with a timeline that may have been a little too tight for extra rewrites. The first few books were very well written and easy to follow, but as the fourth, fifth and sixth came up I could see they were being rushed. Continuity errors, grammar and spelling, and even mixing up character names a few times. It really slows down the read when something like that happens because if one has a wrong name used as a dialogue attribute and doesn’t put comma’s in the right places, it can be like a giant speed bump in a read, until I can figure out whose voice it is supposed to be and what exactly they mean by the unpunctuated words they’re supposed to be saying.

Rewrites can help not only you and your story to be better for the end customer, it also helps a lot if your book is going into audiobook, which accounts for about 30% of book sales these days. And it is nice when someone asks a narrator what their current project is, for that narrator not to reply, “Polishing turds.”

Make it shine! So your narrator can launch it into the stratosphere!

Your points, Basil, underscore the idea that it isn’t a bad idea to READ your draft out loud. As your experience tells us, actually hearing the book can make many of its weaknesses easy to see…or hear. When I finally worked up the guts to listen to one of my books on tape, I was amazed at how different it sounded than the book “tape” that ran in my head as I wrote it.

I love your “show” on rewriting, PJ. Sometimes, newer writers have the impression that “real” writers don’t have to do this step.

Your list of basics to check is excellent.

It’s lovely to have a genuinely successful author not only verify the need for rewrites but to share what the process looks like in progress. Rewriting is not always easy to accomplish, but it’s oh so worth it in the end product.

It never gets any easier, Suzannne. 🙂

I could be looking at the print read-through on one of my own books! Although I do spell out “enough!” 😉

And I totally agree; I find so many things reading a hard copy that I read right past on the screen. Although I also do a final read through on my Kindle, because the brain thinks it’s then reading a published book and is much more picky.

To each their own process, but thanks, I feel less weird. 🙂

Yup…every writer has to create their own process. But I have learned, over the decades, from seeing how others make their sausage.

So helpful–and cool!–to get a look into another author’s mind. Thanks for your generosity!

You’re welcome, Sheri. Actually, going thru and pulling out some of these pages make me find a couple graphs to throw out that I had missed.

Wow. Loved seeing your process, Kris. I edit my previous day’s work before moving forward, but that doesn’t prevent me from nitpicking it to death later.

Nothing beats a good editor, I couldn’t agree more. One time I missed something that seemed so minor, one word that changed the entire scene’s plausibility. A character shot an intruder in the chest (instead of the shoulder or arm) and he sprang to his feet. My editor had a field day with that one. After I learned that important lesson (one word has the ability to destroy a scene), I became a neurotic about details.

Hope you get out of rewrite hell soon!

Try reading Larry Brooks’ book on story engineering. If you know the story before you right it and have the major scenes in mind, it’s just filling in the blanks, you can cut re-writing in half. If you have it worked out before you start things go much better.