I just looked back at the first post I wrote for The Kill Zone in 2015.

2015??? How can that be???

My debut here came about because one of TKZ’s founding mothers, Kathryn Lilley, invited me to write a guest post about self-editing based on a workshop I presented at a conference.

For years, TKZ had been my favorite writing blog so I was thrilled by the chance but also nervous. At that point, none of my books had been published yet. Every contributor here had waaaaaay more experience and accomplishments than I did. But I’d edited a number of books and knew a little something about that topic. So that’s what I wrote about.

Today I’m dusting off that early post to see if editing has changed in the past decade.

Self-Editing Pop Quiz

This morning, let’s imagine we’re back in school and the teacher announces a pop quiz to test your self-editing skills. Did you do your homework?

1. Scan your WIP and highlight every form of the verb “to be.” How many times per page did you use:

is

are

am

was/were

had been

Tally your score:

Fewer than 5 per page: Excellent

Between 5 and 10 per page: Very good, but could use more active verbs

More than 20 per page: Work on how to “de-was” with strong, active, specific verbs.

Many years ago, I took a workshop from the late, great Montana mystery author James Crumley. He shared with me how to “de-was” and I’ve never forgotten. This single skill goes a long way to transform your writing into active, muscular prose.

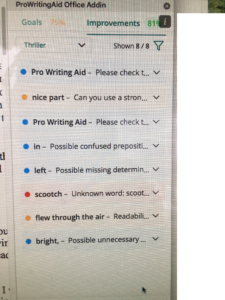

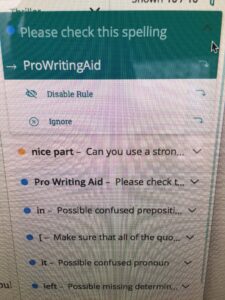

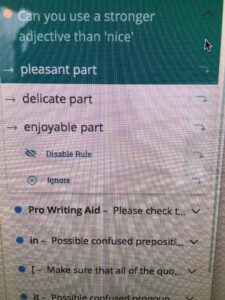

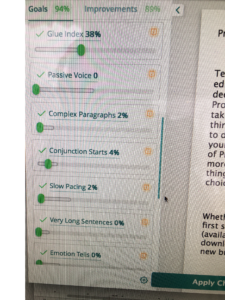

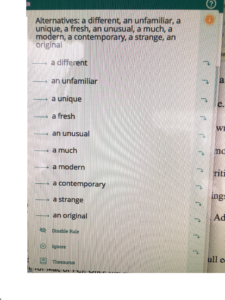

2026 note – De-was-ing still works. Grammar/editing software suggests ways to rewrite in active voice.

2. Read the first few paragraphs of each new scene or chapter. Can a reader quickly determine:

WHO is present?

WHERE they are?

WHEN is the scene taking place?

If you can answer these questions, you’ve done a good job of orienting your reader immediately in the story world. Give yourself a point each time you effectively set the scene.

2026 note: Yup, this still applies.

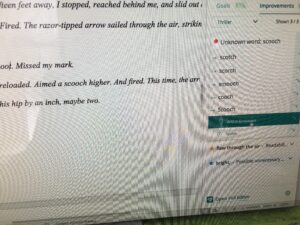

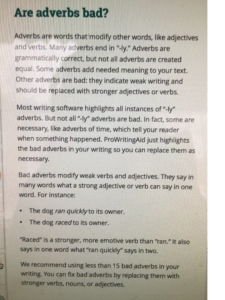

3. Do a global search for what I call “junk” words that add little information and dilute the power of your prose. Score a point every time you delete one of the below “junk” or “stammer” words.

There is (was)

it is (was)

that

just

very

nearly

quite

rather

sort of

turned to

started to

began to

commenced to

Editor Jessi Rita Hoffman calls the last four examples “stammer verbs” that weaken the verb that follows, i.e. Barbara began to race to escape the zombie.

Stronger version: Barbara raced to escape the zombie.

Stammer verb exception: when an action is interrupted or changed, i.e. Robert started to run, but tripped over the corpse.

2026 note: still applies.

4. How many of your characters’ names start with the same letter?

Deduct a point if you’ve christened more than two characters with the same first letter, i.e. Michael, Mallory, Millie, Moscowitz, Melendez.

Deduct a point for rhyming or similar-sounding names: Billy, Lily, Julie.

Extra credit: if none of your characters’ names ends with “S,” give yourself a point for avoiding the unnecessary complication of figuring out whether it should be “Miles’s machine gun,” or “Miles’ machine gun.”

2026 note: still applies.

5. Do you exploit all five senses? Writers most often use sight and hearing, and ignore the other senses that can add texture and richness to the reader’s immersion in the story world.

Give yourself a point each time you employ one of the under-used senses of taste, touch, and smell.

Extra credit: for dramatic effect, deprive your characters of normal sensory input, i.e.

A blindfolded kidnap victim who cannot see where captors are taking her.

An explosion-deafened soldier who cannot hear the enemy stalking him.

2026 note: sensory detail still immerses readers in the story world.

6. The English language constantly challenges even experienced authors. In the eyes of editors and agents, improper usage of common words marks a writer as an amateur. Choose the correct word for each of the following:

(a) It’s [or] its a beautiful day in the neighborhood.

(b) The bear retreated to its [or] it’s den as winter closed in.

(c) Hurricane Katrina effected [or] affected every home in New Orleans.

(d) The affect [or] effect of Hurricane Katrina continued long after the rains ended.

(e) After the lobotomy, McMurphy possessed a flat affect [or] effect.

(f) The farther [or] further the boat drifted from the shore, the harder Joe paddled.

(g) The further [or] farther you pursue this tangent, the more you lose credibility.

(h) The magician made an allusion [or] illusion to Houdini’s famous “vanishing elephant”illusion [or] allusion.

(i) Robert implied [or] inferred that Janet was a tramp.

(j) Since Janet had been convicted of prostitution, Robert inferred [or] implied she was a tramp.

(k) The witness that [or] who saw the assault ran away.

(l) Winston tastes good like [or] as a cigarette should. (Trick question for those of a certain age.)

Answers at the end. Score 1 for each correct answer.

The Elements of Style by Strunk and White is my go-to reference whenever I’m not sure of correct word usage. I find answers to 98% of my questions in Strunk and White.

2026 note: Word (and other writing programs) now do a better job of catching and flagging these misuses.

7. Scan an entire chapter. How many times is the first word of a new paragraph the name of your character or a pronoun referring to that character (he or she)?

8+ out of 10 times – Normal for the first draft, but try varying sentence structure to begin paragraphs in different ways.

5 out of 10 times – Better, but still needs work.

2 out of 10 times – You display good variability in paragraph structure.

2026 note: some writing software flags this problem, as well as makes suggestions how to vary sentence structure.

8. Point of View—do you stay consistently in the same character’s head for the entire scene? Do you switch point of view only when a scene changes or when a new chapter begins?

How many POV changes can you find in the following passage?

Silky sheets caressed Teresa’s naked skin, as her heartbeat quickened. She watched Zack, framed in the doorway, as he unbuttoned his shirt. Secret fantasies he’d harbored for months were about to come true. Teresa’s heavy-lidded eyes promised a welcome worth waiting for. She quivered inside with trepidation. Would he be disappointed or thrilled? With a sweep of his sinewy arm, Zack whipped back the sheet, stunned to discover Teresa was really Terrance.

Answer: Four. The paragraph starts in Teresa’ POV because she feels the sheets and her heartbeat. Then POV switches to Zack and his secret fantasies, which she might guess, but can’t know about since they’re inside his head. Then back to Teresa, quivering inside. Then back to Zack being stunned.

If you struggle with POV, lock yourself inside the head and body of the POV character. Everything that goes on in that scene must be within the eyesight, earshot, or touch of that character. That means the character might be able to look at his own feet, but he can’t see the broccoli stuck in his teeth. Only another character can do that…and I certainly hope she tells him about it soon!

2026 note: a consistent POV is still important to avoid confusing readers.

9. Is the action described in chronological order? Does cause lead to effect? Does action trigger reaction? Is the choreography clear to the reader? Who is where doing what to whom?

If you understand the last sentence, give yourself 10 points and deduct 10 points from my score!

How would you rewrite the following confusing sentence?

George slashed Roger’s throat with the knife as he grabbed him from behind after he sneaked into the warehouse.

How about: Knife in hand, George sneaked into the warehouse, grabbed Roger from behind, and slashed his throat.

Just as messy, but much clearer to the reader because events unfold in the order they happened.

2026 note: writing events in clear, logical order is still important. I don’t know how well editing software addresses this problem because I do it myself.

10. Do you read your work out loud? If so, give yourself an automatic 10 points.

When you read out loud, you catch repeated or missing words, awkward phrasing, and sentences that are too long. “Glide” is the term used by author/editor Jim Thomsen to describe smooth, effortless, clear writing. Glide is like riding in a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce as opposed to bucking and shuddering in a 1973 Pinto with bad spark plugs and a flat tire.

For extra credit, have someone else read your work out loud. If he or she can read without stumbling, you’ve achieved glide. Award yourself 25 bonus points.

2026 note: reading aloud still works but now many programs read to you. That saves a sore throat.

Answers to 6 (a) it’s, (b) its, (c) affected, (d) effect, (e) affect, (f) farther, (g) further, (h) allusion, illusion, (i) implied, (j) inferred, (k) who, (l) Despite the catchy slogan from the 1950s, correct use would be as. Back then, liquor couldn’t advertise on TV, but cigarettes could. Now liquor ads are common, but few people even remember commercials for cigarettes. How times change!

How did you do? Tell us in the Comments!

Fewer errors equal less distractions and a more engaged reader. A more engaged reader equals more sales.

And that equals an A+.

~~~

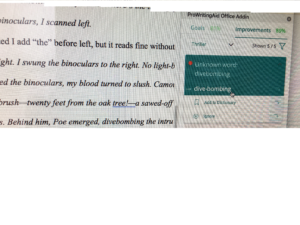

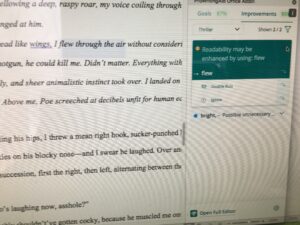

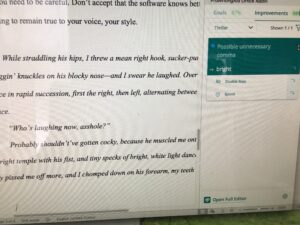

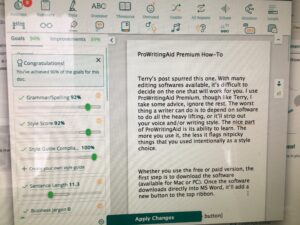

Revisiting this early post, the same principles apply. The main difference between then and now is that more editing software programs are available to alert the writer to potential problems.

~~~

TKZers: how did you do on the quiz? Please answer in the comments.

Extra credit if you caught my error in the original. In 2015, an alert reader busted me.

Do you use editing software? Which ones do you prefer?

~~~

On March 5, I’m teaching a zoom webinar entitled “It’s 10 p.m. Do You Know Where Your Villain Is.” Click this link for more information.

That topic began as a TKZ post and grew into my book, The Villain’s Journey-How to Create Villains Readers Love to Hate. Sales link.

Go on a global search-and-destroy mission for the following words/phrases:

Go on a global search-and-destroy mission for the following words/phrases: