by Debbie Burke

A couple of weeks ago, I attended the Montana Writers Rodeo and wrote a post about the fun, enlightening conference experience.

Today, here are the 10 tricks (plus one bonus tip) from my workshop at the Rodeo on how to edit your own writing.

Newer writer: “Why should I worry about spelling, grammar, and typos? The editor will fix them.”

Hate to break the news but that ain’t gonna happen.

Being a professional means we’re responsible for quality of the book we turn out.

Whose name is on the cover?

Ours.

If there are errors, who gets blamed?

We do.

That’s an important reason to hone our own editing skills.

Whether you go the traditional route or self-publish, a well-written story without typos and errors increases your chance of successful publication.

Due to layoffs, fewer editors work at publishing houses. Those who remain are swamped with other tasks, leaving little time to actually edit. In recent years, I’ve noticed an uptick in grammar, punctuation, and spelling goofs in traditionally published books.

If you indie-pub, a book with errors turns off readers.

The overarching goal of authors is to make the writing so smooth and effortless that readers glide through the story without interruption.

We want them to become lost in the story and forget they’re reading.

How can we accomplish that? By self-editing to the best of our ability.

As a freelance editor, what do I look for when I review a manuscript?

- Is the writing clear and understandable?

- Do stumbling blocks and awkward phrases interrupt the flow?

- Are there unnecessary words or redundancies?

- Are there nouns with lots of adjectives?

- Do weak verbs need adverbs to make the action clear?

Here are my 10 favorite guidelines. Please note, I said guidelines, not rules!

1. Delete the Dirty Dozen Junk Words –  Go on a global search-and-destroy mission for the following words/phrases:

Go on a global search-and-destroy mission for the following words/phrases:

It is/was

There is/was

That

Just

Very

Really

Quite

Almost

Sort of

Rather

Turned to…

Began to…

Getting rid of unnecessary junk words tightens writing and makes stronger sentences.

Clear, concise narrative is your mission…with the exception of dialogue.

Characters ramble, stammer, repeat themselves, and backtrack. Natural, realistic-sounding dialogue uses colloquialisms, regional idiosyncrasies, ethnic speech patterns, etc.

Photo credit: Wikimedia

But, like hot sauce, a little goes a long way.

At the Rodeo, actor/director Leah Joki used excerpts from Huckleberry Finn to illustrate the power of dialogue.

But hearing it is different from reading it. If overdone, too much dialect can make an arduous slog. Imagine translating page after page of sentences like this one from Jim in Huck Finn:

“Yo’ ole father doan’ know yit what he’s a-gwyne to do.”

- Set the stage – At the beginning of each scene or chapter, establish:

WHO is present?

WHERE are they?

WHEN is the scene happening?

If you ground the reader immediately in the fictional world, they can plunge into the story without wondering what’s going on.

- Naming Names – Distinctive character names help the reader keep track of who is who.

Create a log of character names used.

Easy trick: write the letters of the alphabet down the left margin of a page. As you name characters, fill in that name beside the corresponding letter of the alphabet. That saves you from winding up with Sandy, Samantha, Sarah, Sylvester.

Vary the number of syllables, e.g. Bob (1), Jeremiah (4), Annunciata (5).

Avoid names that look or sound similar like Michael, Michelle, Mickey.

Avoid rhyming names like Billy, Milly, Tilly.

- Precision Nouns, Vivid Verbs – Adjectives and adverbs are often used to prop up lazy nouns and verbs. Choose exact, specific nouns and verbs.

Instead of the generic word house, consider a specific noun that describes it, like bungalow, cottage, shanty, shack, chateau, mansion, castle. Notice how each conjures a different picture in the mind.

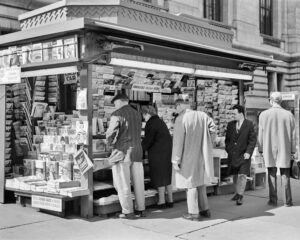

Photo credit: wikimedia CC BY 2.0 DEED

Holyroodhouse

Photo credit: Christophe Meneboeuf CC-BY-SA 4.0 DEED

Instead of the generic verb run, try more descriptive verbs like race, sprint, dart, dash, gallop. That gives readers a vivid vision of the action.

- Chronology and Choreography – Establish the timeline.

Photo credit: IMDB database

Quentin Tarantino can get away with scenes that jump back and forth in time like a rabid squirrel on crack.

But a jumbled timeline risks confusing the reader. Unless you have a compelling reason to write events out of order, you’re probably better off sticking to conventional chronology.

Are actions described in logical order? Does cause lead to effect? Does action trigger reaction?

Chronology also applies to sentences. In both examples below, the reader can figure out what’s going on, but which sentence is simpler to follow?

- George slashed Roger’s throat with the knife as he grabbed him from behind after he sneaked into the warehouse.

- Knife in hand, George sneaked into the warehouse, grabbed Roger from behind, and slashed his throat.

In theatre, actors and directors block each scene. Clear blocking helps the reader visualize events and locations.

Establish where the characters are in relation to each other and their surroundings.

Map out doors, windows, cupboards, stairwells, secret passages, alleys, etc. where a bad guy might sneak up on the hero, or where the hero might escape.

Locate weapons.

Does the hero or the villain carry a gun or knife? Establish that before the weapon magically appears.

Pre-place impromptu weapons (golf club, baseball bat, scissors) where the hero can grab them in an emergency. Or put them just out of reach to complicate the hero’s struggle.

- When to Summarize? When to dramatize?

Photo credit: Public Domain

Summarize or skip boring, mundane details like waking up, getting dressed, brushing teeth…unless the toothpaste is poisoned!

Dramatize important events and turning points in the story, such as:

- New information is discovered.

- A secret is revealed.

- A character has a realization.

- The plot changes direction.

- A character changes direction.

7. Dynamic description – Make descriptive passages do double duty.

Rather than a driver’s license summary, show a character’s personality through their appearance and demeanor.

Static description: He had black hair, brown eyes, was 6’6″, weighed 220 pounds, and wore a gold shield.

Dynamic description: When the detective entered the interview room, his ‘fro brushed the top of the door frame. His dark gaze pierced the suspect. Under a tight t-shirt, his abs looked firm enough to deflect a hockey puck.

Put setting description to work. Use location and weather to establish mood and/or foreshadow.

Static description: Birds were flying. There were clouds in the sky. An hour ago, the temperature had been 70 degrees but was now 45. She felt cold.

Dynamic description: Ravens circled, cawing warnings to each other. In the east, thunderheads tumbled across a sky that moments before had been bright blue. Rising wind cut through her hoody and prickled her skin with goosebumps.

- Read Out Loud – After reading the manuscript 1000+ times, your eyes are blind to skipped words, repetitions, awkward phrasing.

To counteract that, use your ears instead to catch problems.

Read your manuscript out loud and/or listen to it with text-to-speech programs on Word, Natural Reader, Speechify, etc. Your phone may also be able to read to you. Instruction links for Android and iPhone.

- Be Sensual – Exploit all five senses. Writers often use sight and hearing but sometimes forget taste, smell, and touch that evoke powerful memories and emotions in readers.

Think of the tang of lemon. Did you start to salivate?

Smell the stench of decomposition. Did you instinctively hold your breath and recoil?

Photo credit: Amber Kipp – Unsplash

Imagine a cat’s soft fur. Do your fingers want to stroke it?

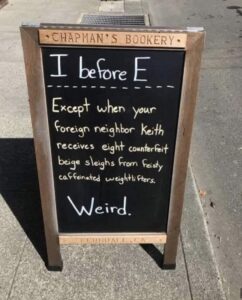

- What’s the Right (Write) Word? – English is full of boobytraps called homophones, words that sound the same but don’t have the same meaning.

Spellcheck doesn’t catch mixups like:

its/it’s

there/they’re/their

cite/site/sight, etc.

Make a list of ones that often trip you up and run global searches for them. Or hire a copyeditor/proofreader.

Bonus Tip – When proofreading, change to a different font and increase the type size of your manuscript. That tricks the brain into thinking it’s seeing a different document and makes it easier to spot typos.

Self-editing is not a replacement for a professional editor. But when you submit a manuscript that’s as clean and error-free as you can make it, that saves the editor time and that saves you $$$ in editing fees!

Effective self-editing means a reader can immerse themselves in a vivid story world without distractions.

And isn’t that what it’s all about?

~~~

TKZers: What editing issues crop up in your own writing?

Do you have tricks to catch errors? Please share them.

When you read a published book, what makes you stumble?

~~~

One reason Debbie Burke likes indie-publishing: goofs are easy to correct. In Dead Man’s Bluff, she discovered FILES were circling an animal carcass instead of FLIES. Took two seconds to fix and republish.

Available at all major online booksellers.

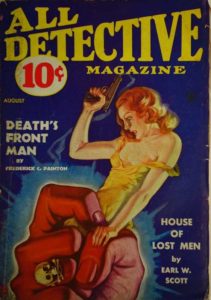

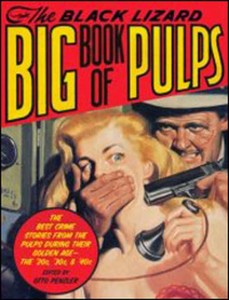

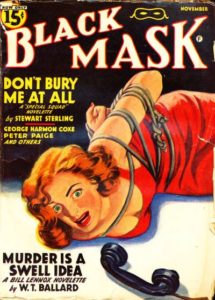

People want stories. I would argue people need stories. That’s how the great pulp writers made their living—providing fast-moving tales for readers who longed for escapism, especially during the Great Depression.

People want stories. I would argue people need stories. That’s how the great pulp writers made their living—providing fast-moving tales for readers who longed for escapism, especially during the Great Depression.