By P.J. Parrish

Now pay attention, kittens and bo’s, there’s a quiz at the end of this one.

I was an art major in college. This was before I figured out I couldn’t make a living at this. Unless I planned to teach, but I was scared of kids. (Not a good character trait in teachers). I was doing okay in art until I hit a class called Three Dimensional Design. I could draw and paint but I was terrible at this. Evidence of my ineptitude was my “final exam” sculpture, which I called Nude With A Paper Cup Head. So titled because I couldn’t get my figure’s face right so I just filled a Dixie cup with wet plaster and stuck it on top. I got a D.

I just didn’t get it. I couldn’t think outside the two-dimensional box. Finally, my instructor told me I had to stop seeing the world in POSITIVES and start seeing it in NEGATIVES. In other words, I was so hung up on adding things, I was missing the beauty of subtracting. “Learn how to leave things out,” he told me.

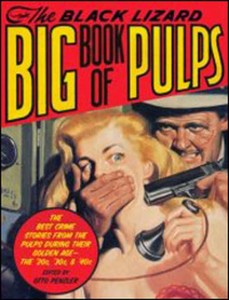

I ended up abandoning art for writing. But I think that little piece of advice must have lodged deep in my brain cells because it is something subconsciously I have always tried to apply to my fiction writing. Subconsciously I say because until recently, I hadn’t even thought about my art instructor and his advice. Maybe I am thinking about it now because of the book I am reading — “The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps.” I got it for Christmas but I keep it handy by the bedside, digesting it in small doses.

It’s a handsome book…a compiliation of the best crime stories from the “golden age” of pulp crime fiction — the 20s through the 40s. It’s about the size of the Manhattan phone book. And to be really honest, parts of it read about as well.

Many of these guys were dismissed as the hacks of their day, churning out their stories for cheaply printed magazines like “Black Mask” and “Dime Detective.” Yeah, they were lurid, the syntax cringe-worthy, the plots thin or nonsensical. But they tapped into a popular need for a new kind of human hero. The most memorable of the heroes became the prototypes for much of what we are seeing in our crime fiction today — lone wolves fighting for justice against all odds but always on their own different-drummer terms. Would we have Harry Bosch without the Continental Op? Jack Reacher without Simon Templar? Doubtful…

Some of my favorite “classic” crime writers wrote pulp. Like John D. MacDonald who churned out stories for “Black Mask” and “Dime Detective,” and Donald Westlake writing as Richard Stark. Even my seminal hero Georges Simenon (creator of inspector Maigret who was a partial inspiration for my own protag Louis Kincaid) couldn’t resist the lure of the lurid and wrote two nasty little noirs call “Dirty Snow” and “Tropic Moon.”

To be sure, not all the stories in “Lizard” have aged well. The slang sounds vaguely silly now, the sexism and racism we can explain away as anachronistic attitudes. But the armature these writers created is still sturdy.

Especially in pure writing style. That is the biggest thing I am getting out of these stories, an appreciation for that streamlined locomotive style that propels these stories along their tracks. I read these stories now — discovering most of these writers for the first time — with a smile on my face and a Highlighter in hand. There are lessons to be learned for us all, and you can almost hear James M. Cain whispering: “I’m not going to dazzle you with my writing. I’m going to tell you a helluva story.”

These guys sure knew what to leave out. Let me give you one little passage from Paul Cain’s “One Two Three”:

I said: “Sure — we’ll both go.”

Gard didn’t go for that very big, but I told him that my having been such a pal of Healy’s made it all right.

We went.

Not: And then we left the apartment and got in my roadster and set out. We took Mulholland Drive out of the canyon and arrived just before dusk.

Just: We went.

How can you read that and not smile?

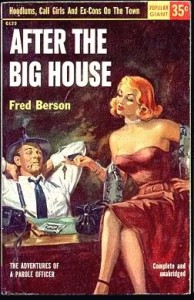

I heartily recommend the “Big Book of Pulps.” And speaking of art, check out some of the best pulp cover artists of the day at Rex Parker’s terrific vintage paperback blog

Pop Sensation. And now, in honor of our pulp forefathers, I am offering up this little quiz of pulp slang for your amusement. Answers at the end. And don’t chance the chisel for a cheap bulge, bo. We Jake?

DEFINITIONS.

1. Ameche

2. Kicking the gong around

3. Wooden kimono

4. cheaters

5. Gasper

6. Hammer and saws

7. Orphan papers

8. Wikiup

9. Bangtails

10. Can-opener

TRANSLATIONS

11. I had been ranking the Loogan for an hour and could see he was a right gee. It was all silk so far.

12. I stared down at the stiff. The bim hadn’t been chilled off. Definitely a pro skirt who had pulled the Dutch act.

13. I got a croaker ribbed up to get the wire.

14. By the time we got to the drum the droppers had lammed off. Another trip for biscuits…

Answers:

1. telephone

2. taking opium

3. coffin

4. sunglasses

5. cigarette

6. Police

7. Bad checks

8. Home

9. Horses

10. Safecracker

11. I had been watching the man with the gun for an hour and could tell he was an okay guy. Everything was cool so far.

12. I stared at the body. The woman hadn’t been murdered. She was definitely a prostitute who had committed suicide.

13. I have arranged for a doctor to get the information.

14. By the time we got to the speakeasy, the hired killers had left. Just another trip for nothing…