Category Archives: Donald Westlake

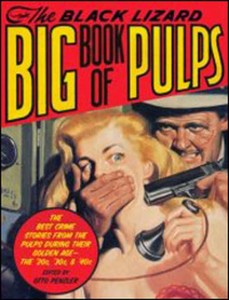

What we can learn from pulp fiction

Now pay attention, kittens and bo’s, there’s a quiz at the end of this one.

Especially in pure writing style. That is the biggest thing I am getting out of these stories, an appreciation for that streamlined locomotive style that propels these stories along their tracks. I read these stories now — discovering most of these writers for the first time — with a smile on my face and a Highlighter in hand. There are lessons to be learned for us all, and you can almost hear James M. Cain whispering: “I’m not going to dazzle you with my writing. I’m going to tell you a helluva story.”

I said: “Sure — we’ll both go.”

Gard didn’t go for that very big, but I told him that my having been such a pal of Healy’s made it all right.

We went.

First Person Boring

I love a good First Person POV novel. I love writing FP myself. But there are perils, and if you’re thinking of trying your hand at it you’re going to need be aware of them.

One of these is the “I’m so interesting” opening that is anything but.

Recently I read a couple of novels in FP that had this problem. They began with the narrator telling us his name and giving us a chapter of backstory. By the time I finished the opening chapter I was thinking, Why am I even listening to you?

Let me illustrate. You go to a party and see a guy standing off to the side, you nod and introduce yourself, and he says, “Hi. My name is Chaddington Flesch. Most people call me Cutty, because my grandfather, Bill Flesch, refused to call me anything else. He liked Cutty Sark, you see, and thought this name would make a man out of me. All through school I had to explain why I was called Cutty. Growing up in Brooklyn, that wasn’t always easy. Even today, at my job, which happens to be as an accountant, I . . .”

Yadda yadda yadda. And you’re standing there at this party thinking, Dude, I’m sorry, but I don’t especially care about your history. I have a history, everybody at this party has a history. Nice meeting you, but . . .

But what if you introduce yourself to the guy and he says, “Did you avoid the cops outside?”

You look confused.

“Because I got stopped by a cop right out there on the street. He tells me to hit the sidewalk, face down, and then proceeds to kick me in the ribs. I say, ‘There’s been a mistake.’ He gets down in my face and says, ‘You’re the mistake. I’m the correction.'”

What are you thinking then? Either: Am I talking to a criminal? Or, What happened to this poor guy?

What your reaction isn’t is bored.

You are hooked on what happened to him. And that’s the key to opening with FP. Open with the narrator describing action and not dumping a pile of backstory.

Save that stuff for later.

Open with movement, with action.

I got off the plane at Maguire, and sent a telegram to my dad from the terminal before they loaded us into buses. Two days later, the Air Force made me a civilian, and I walked toward the gate in my own clothes, a suitcase in each hand.

I was a mess.

[361 by Donald Westlake]

The girl’s name was Jean Dahl. That was all the information Miss Dennison had been able to pry out of her. Miss Dennison had finally come back to my office and advised me to talk to her. “She’s very determined,” my secretary said. “I just can’t seem to get rid of her.”

Then Miss Dennison winked. It was a dry, spinsterish, somewhat evil wink.

[Blackmailer by George Axelrod]

The nun hit me in the mouth and said, “Get out of my house.”

[Try Darkness by James Scott Bell]

Now I realize I’ve used hardboiled examples here, and some of you favor more literary writing. There’s a lot of debate on just how you define “literary,” but let me suggest that literary does not have to mean leisurely. You can still open with a character in motion in a literary novel, and I guarantee you your chances of hooking an agent or editor, not to mention a reader, will go way up without any other effort at all.

One of my biggest tips to new writers is the “Chapter 2 Switcheroo.” I can’t tell you how many times I’ve looked at a manuscript and suggested that Chapter 1 be thrown out and Chapter 2 take over as the new opening. I would say, conservatively, that 90% of the time it makes all the difference, because the characters are moving. There’s action. Something is happening. And truly important backstory can be dribbled in later. Readers will always wait patiently for backstory if your frontstory is moving.

Try it and see.