by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

On July 14 I’ll be leading a panel at ThrillerFest on literary influences. The guests are David Morrell, Lisa Gardner, Ted Bell, Peter Blauner, Robert Gleason and W. Michael Gear. Still time to register for TFest. Hope to see some of you there.

That subject got me thinking about the authors who have influenced me, so I thought from time to time I’d write about them, and some of the lessons learned.

I begin with John D. MacDonald. For those of you unfamiliar with his work, here’s a clip from The Red Hot Typewriter by Hugh Merrill:

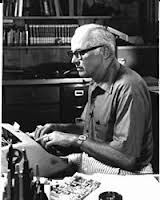

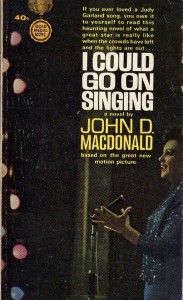

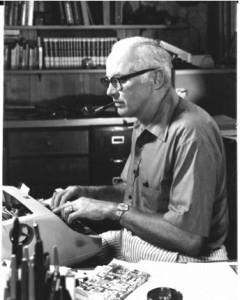

From the 1950s through the 1980s, John Dann McDonald was one of the most popular and prolific writers in America. He was a crime writer who managed to break free of the genre and finally get serious consideration from critics. Seventy of his novels and more than 500 of his short stories were published in his lifetime. When he died in 1986, more than seventy million of his books had been sold.

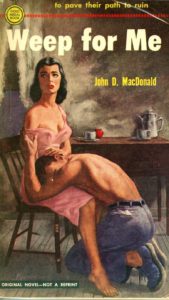

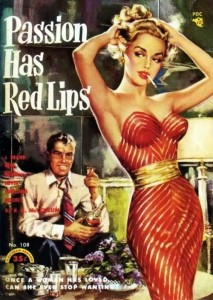

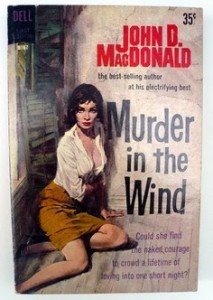

I first became seriously interested MacDonald when I read that he was one of Dean Koontz’s favorite writers. I’d read a couple of the Travis McGee books, for which MacDonald is most famous. But it was when I picked up some of his 1950s paperback originals that I really got into him. I went on a collecting binge for several years and now have a full collection of said paperbacks, including the one hardest to get, Weep For Me (1951). MacDonald refused to let it be reprinted. He was embarrassed by it, calling it a lousy imitation of James M. Cain. (I went to her in that shadowy place under the concrete arch. The early traffic slammed across the bridge, tearing the air. I took what I had won, the way any animal does.) It’s better than that (the folks at Random House have decided to give it life again) but was still hewing to the minimalist style popularized by Cain, Hammett, and Spillane—who were all beholden to Hemingway.

I first became seriously interested MacDonald when I read that he was one of Dean Koontz’s favorite writers. I’d read a couple of the Travis McGee books, for which MacDonald is most famous. But it was when I picked up some of his 1950s paperback originals that I really got into him. I went on a collecting binge for several years and now have a full collection of said paperbacks, including the one hardest to get, Weep For Me (1951). MacDonald refused to let it be reprinted. He was embarrassed by it, calling it a lousy imitation of James M. Cain. (I went to her in that shadowy place under the concrete arch. The early traffic slammed across the bridge, tearing the air. I took what I had won, the way any animal does.) It’s better than that (the folks at Random House have decided to give it life again) but was still hewing to the minimalist style popularized by Cain, Hammett, and Spillane—who were all beholden to Hemingway.

In those early years MacDonald wrote science fiction, hard-boiled detective, crime, contemporary adult, and even a multi-protagonist novel (The Damned) centered around a single event, influenced no doubt by Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey.

One theme he returned to was the existential angst of the 50s man. His 1953 novel, Cancel All Our Vows, is superior to Sloan Wilson’s more famous The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1955). It’s the story of one Fletcher Wyant, age 36, a middle manager at a big company. The following passage is quintessential MacDonald:

And, as he was looking, it happened to him again. It was something that had started with the first warm days of spring. All colors seemed suddenly brighter, and with his heightened perception, there came also a deep, almost frightening sadness. It was a sadness that made him conscious of the slow beat of his heart, of the roar of blood in his ears. And it was a sadness that made him search for identity, made him try to re-establish himself in his frame of reference in time and space. Fletcher Wyant. He of the blonde wife and the kids and the house and the good job. It was like an incantation, or the saying of beads. But the sadness seemed to come from a feeling of being lost. Of having lost out, somehow. He could not translate it into the triteness of saying that his existence was without satisfaction. He was engrossed in his work and loved it. He could not visualize any existence without Jane and the kids. Yet, during these moments that seemed to be coming more frequently these last few weeks, he had the dull feeling that somehow time was eluding him, that there was not enough of life packed into the time he had.

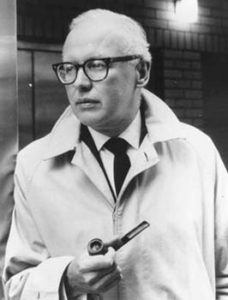

When MacDonald finally settled on writing mostly crime fiction, he produced some true classics, like The End of the Night, which pre-dated Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, and The Executioners, the basis of the movie Cape Fear. (Note: The 1962 Gregory Peck-Robert Mitchum version is better than the 1991 Robert De Niro-Nick Nolte remake directed by Martin Scorsese, though it was a nice gesture to give both Peck and Mitchum minor roles in that one.)

There’s a great story around the writing of The Executioners. MacDonald regularly met with a group of writers in Florida, one of whom was MacKinlay Kantor. Kantor, who had won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction, used to needle MacDonald about all the “paperback trash” he wrote. One day he asked John, “When are you going to write a real book?”

MacDonald was ticked. He said he could write a book in thirty days that would be serialized in a magazine, become a book club selection, and be turned into a movie. Kantor laughed. MacDonald bet him fifty bucks. And, of course, won.

The first lesson I picked up from a wide reading of MacDonald is what he termed “unobtrusive poetry” in the style. That’s not an easy thing to accomplish. You don’t want a style that calls so much attention to itself that’s all the reader is thinking about. On the other hand, it’s not stripped-down minimalism of the Hemingway-Cain school.

MacDonald found the right place. His books are filled with passages that capture a character or setting with just a few incandescent lines. Here’s an example from one of the Travis McGee books, Darker Than Amber:

She sat up slowly, looked in turn at each of us, and her dark eyes were like twin entrances to two deep caves. Nothing lived in those caves. Maybe something had, once upon a time. There were piles of picked bones back in there, some scribbling on the walls, and some gray ash where the fires had been.

I’ve never forgotten that image. Indeed, I believe MacDonald could have been one of our best mainstream writers, a Book-of-the-Month Club darling like Norman Mailer or John O’Hara. He could have written “big” books that weren’t disasters. But his paperbacks paid the bills, and that’s what he kept producing.

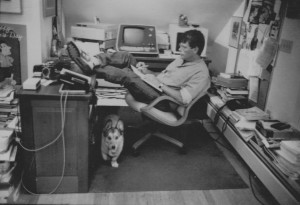

Which brings me to another aspect of his career that inspired me—his work ethic. MacDonald came out of corporate America and approached his writing like a job. He wrote each day from morning till noon, had lunch, went back to work and knocked off at five for a martini and dinner. He took Sundays off.

MacDonald also left behind a legacy of short stories. Two collections of his crime and mystery stories are The Good Old Stuff and More Good Old Stuff. But I think I prefer his more literary collection, End of the Tiger. One of the stories, “The Bear Trap,” inspired me to try my own hand at this type of tale. So in honor of JDM, I’m making my story “Golden” free this week. Enjoy.

John D. MacDonald was once asked how he’d like his epitaph to read. His answer: “He hung around quite a while, entertained the folk, and was stopped quick and clean when the right time came.”

MacDonald’s time came much too soon. He died at age 70 from complications arising out of heart surgery. He left his wife an estate worth $5 million (in 1986 dollars) and left the rest of us some really good stuff. Not a bad way for a writer to go after all.