Please welcome today’s Brave Author who submitted the first page of The Recruiter for feedback. Enjoy the excerpt then we’ll talk about it.

~~~

The butt of the revolver smashed into my face, slicing open a half-inch gash above my left eyebrow. I pressed a hand to my bleeding forehead and cursed.

“You have a smart mouth,” Mr. White said.

“And you’re wasting my time,” I replied, feeling the sting of sweat in the wound. As soon as I pulled my hand away, I could feel the blood begin to pool again. In a few seconds it would trickle down and stain both my shirt and suit jacket a deep red.

Shit. I just had them both dry cleaned.

“Your time is my time,” Mr. White said. With his thick Eastern European accent, the line sounded more cartoonish than I bet he intended.

“Not until you pay me it isn’t. And for the past half-hour I’ve sat here and answered questions about everything from my shoe size to my favorite porn star.” I turned to the hired muscle standing behind me, the one whose gun now had drops of my blood on its handle. Guy was wearing Ray Bans even though it was 1:30 in the morning and we were inside an empty bar. Douchebag. “By the way,” I said to him, “my favorite porn star? It’s your Mom.”

This time the butt came down on the back of my neck. I almost passed out but bit my tongue until the gray spots in my vision disappeared. I spat a mouthful of pink saliva onto the dirty floor and sat up.

“I’m a thorough businessman,” Mr. White said as he twisted a pinkie ring between his thumb and forefinger. Another unintentionally cartoonish move. “And I don’t make deals with someone based solely on their reputation without asking some questions of my own.”

“Cut the shit. My reputation is the only reason your boy hasn’t blown my brains out all over this table and we both know it.” To that, neither man had a reply. “So if you’re done with the HR interview, let’s talk about why I’m sitting here, because it sure as hell isn’t for the company.”

Mr. White twisted his pinkie ring a few more times–gold, of course, and shiny–before he finally smiled. He nodded to Ray Bans and a black briefcase fell on the table in front of me. A thin cloud of dust from broken peanut shells and cigarette ash puffed up where it landed.

~~~

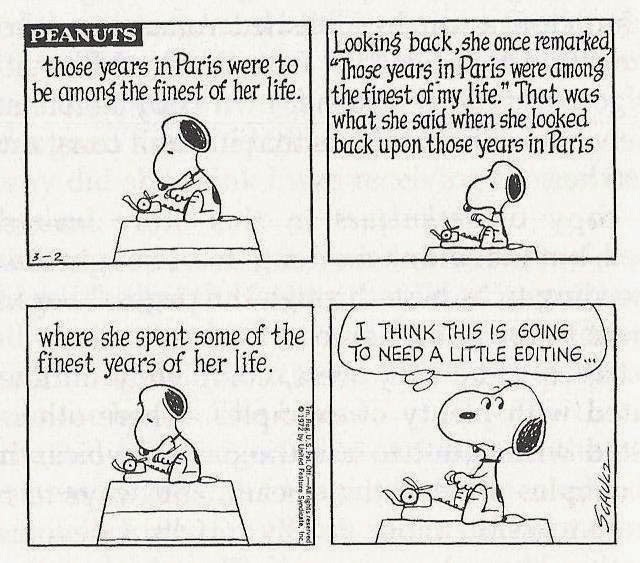

First off, congratulations to today’s Brave Author for an action-packed start. Nothing like the protagonist being pistol whipped to catch the reader’s attention.

Immediately following are a couple of great lines that firmly establish the genre as gritty and hard-boiled:

“In a few seconds it would trickle down and stain both my shirt and suit jacket a deep red.

Shit. I just had them both dry cleaned.”

Clearly, this ain’t the first rodeo for the as-yet-unnamed protagonist. For now, let’s call him Tough Guy or TG.

TG is no stranger to violence. In fact, he provokes it:

“By the way,” I said to him, “my favorite porn star? It’s your Mom.”

That earns TG another thump on the back of his neck.

The Raymond Chandler vibe predisposes me to like this page because Chandler is my all-time favorite author. The writing is crisp, clear, and error-free. The voice is strong and sardonic. The description is sparse but still paints a vivid picture of a grimy, low-end bar.

“A thin cloud of dust from broken peanut shells and cigarette ash puffed up where it landed.”

Good job of drawing the reader deeper into the story with action and unanswered questions. We want to learn who these people are, why they’re meeting, and what’s at stake.

We know Tough Guy isn’t tied up since his hand is free to wipe away blood. That raises more questions: Why does he tolerate being smacked around? Why does he bring more abuse down on himself? To prove his toughness?

Cops, private investigators, and fixers in 1930s and ’40s movies behaved that way and the audience bought it. But contemporary readers will wonder about TG. If he’s really that good, he could–and would–disarm Ray Bans after the first blow. Further, a pro would not risk unnecessary injury simply for the sake of hurling a snarky insult…even though the line about mom being a porn star is very funny.

Here’s a possible different approach: TG baits Ray Bans with the insult about his mom, knowing the guy will retaliate. He’s prepared for the attack and takes the gun away, making RB look stupid in front of his boss. TG also makes himself look smarter and more competent to the reader.

Suggest you identify the protagonist on the first page by having Mr. White address him by name. Two possible opportunities: “You have a smart mouth, Mr. XYZ.” Or “Your time is my time, Mr. XYZ.”

A few small nits:

A revolver is generally perceived as a weapon from an earlier era. Semi-auto pistols with high capacity magazines are more likely to be today’s gun of choice for the well-armed thug.

Unless Tough Guy can see himself, he can’t know the gash is a half-inch long. Suggest you just use “gash” without the measurement.

“I could feel the blood begin to pool again.” Blood wouldn’t pool if it’s running down his face. Blood generally pools on a horizontal surface like a floor or table.

The blood on the gun butt is more likely to be smears than drops.

None of these issues is significant and all are easily fixed.

My biggest concern is the portrayal of Mr. White which veers into clichés. Mr. White’s thick Eastern European accent, pinkie ring, and stock dialogue have been done in countless books and films. The Brave Author even acknowledges that by calling him “cartoonish.”

Unless this is meant to be a satire, like Steve Martin’s Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982), the author might consider a fresher approach to describing the heavy.

There are some great humorous lines.

“Guy was wearing Ray Bans even though it was 1:30 in the morning and we were inside an empty bar. Douchebag.”

“So if you’re done with the HR interview…”

Overall, this page is well written, strong, and compelling. I’m sure Brave Author will find a fresher way to characterize Mr. White.

The excerpt was a pleasure to read. It was also difficult to critique because I found so few problems. All were minor and readily fixable by this obviously capable writer.

A fine job, Brave Author! Thanks for submitting. Let us know when this is published.

~~~

TKZers: What are your thoughts on The Recruiter? Any ideas for the Brave Author? Would you keep reading?

~~~

Coming soon! Debbie Burke’s new novella, Crowded Hearts, will be FREE for a limited time. Watch for the announcement here at TKZ.