by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

How should you approach describing a setting?

How should you approach describing a setting?

I wager most writers come to that point in their project and immediately turn to the imagination. They let pictures form in their minds, then start to write down what they see. Some writers Google around and find an image they can look at before they begin.

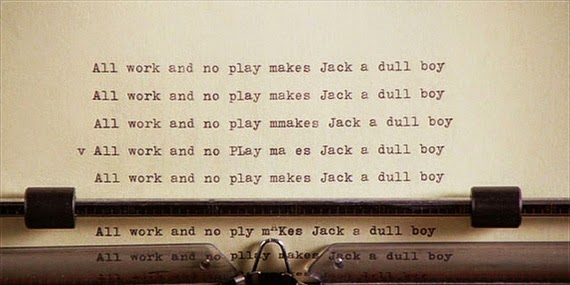

Then it becomes a matter of choosing the details they want to include. However, there’s a subtle trap here that new (and even vet) writers may fall into: the setting description can end up as a dry stack of details:

The conference room was large and cold. It had a big table in the middle, with black leather chairs all around. There was a bookcase on the far side of the room and a credenza with a coffee maker on the other. Floor-to-ceiling windows gave a view of the city.

Now, there’s nothing illegal about this. It does the job in a functional way. But it’s also an opportunity lost. A great setting description doesn’t just paint a picture; it draws the reader deeper into the marrow of the story and the heart of the character.

Which brings me to the most important tip you’ll ever get about writing setting descriptions:

You describe a scene not so the reader can see it, but so the reader can feel it. And the way they feel it is by knowing how the point-of -view character feels about it.

That’s why I’ve developed a seven-step checklist for myself for writing a setting description. It takes a little extra time, but I’ve determined that the stylistic ROI (return on investment) is worth it. Here we go:

- How do you want your character to feel about the setting?

This is the crucial first step, and it’s a strategic one. You know where you are in your story and what the character’s attitudes and emotional landscape are. You know what’s going to happen in the scene (note to pantsers: you’ve at least got some idea). Now you’re going to set the scene through the character’s perceptions about it. Your decision can be as simple as: I want my character to feel intimidated.

Note that you don’t have to name the emotion when you write the scene. In fact, it’s better not to. Let the setting itself create the feeling.

- Using the sense of sight, describe the things the character notices.

The items that come into your mind will now be filtered through the POV character. If you want to locate a picture via the Internet, go ahead. But as you look at it, pretend you are the character and try to feel what she feels. Make a list of the items your character doesn’t just see, but notices. This is a crucial distinction. We focus on different things depending on our mood. If you’re unhappy and you walk into a sunny hotel foyer, you might ignore the fancy art and notice instead a droopy plant.

Do a little voice journaling. Have the character talk to you in her own voice, expressing her feelings about what she notices.

- Use the other senses to add to the feeling.

Imagine what the character might hear, smell, touch, or even in some cases taste. Make a list.

- Look at the items from Steps 2 & 3 and highlight the ones that work best.

That didn’t take long, did it? Five to ten minutes. But if you’re having fun, do more!

- Bonus Supercharger: What is the character’s personal interpretation of the place?

Here is a powerful technique used by some of our best writers: when the character offers his own interpretation of the setting, it not only creates a sense of place, but also deepens the character for the reader. Double score!

Here are a couple of examples. This is from Robert B. Parker’s first Spenser novel, The Godwulf Manuscript:

The Homicide Division was third floor rear, with a view of the Fryalator vent from the coffee shop in the alley and the soft perfume of griddle and grease mixing with the indigenous smell of cigar smoke and sweat and something else, maybe generations of scared people.

Parker uses sight and smell, but also adds generations of scared people. That’s from inside Spenser. That’s his own impression of the place. It tells me as much about Spenser as it does the setting.

Here’s a longer impressionistic description from John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee mystery, The Quick Red Fox. These are McGee’s feelings about San Francisco. (I apologize to all my friends in the City by the Bay!)

And so we drove back to the heart of the city. San Francisco is the most depressing city in America. The comelatelys might not think so. They may be enchanted by the steep streets up Nob and Russian and Telegraph, by the sea mystery of the Bridge over to redwood country on a foggy night, by the urban compartmentalization of Chinese, Spanish, Greek, Japanese, by the smartness of the women and the city’s iron clutch on culture. It might look just fine to the new ones.

But there are too many of us who used to love her. She was like a wild classy kook of a gal, one of those rain-walkers, laughing gray eyes, tousle of dark hair –– sea misty, a little and lively lady, who could laugh at you or with you, and at herself when needs be. A sayer of strange and lovely things. A girl to be in love with, with love like a heady magic.

But she had lost it, boy. She used to give it away, and now she sells it to the tourists. She imitates herself … The things she says now are mechanical and memorized. She overcharges for cynical services.

I think it’s fair to say we know how McGee feels about San Francisco! One of the things that made this series so popular was passages like the above, where McGee riffs on such matters as setting, social mores and current events.

- Write the description using active verbs and concrete images.

At this point, let me advise you to overwrite the description. Don’t try to get this perfect the first time through. Feel it first.

- Let the scene rest, then edit.

I don’t do heavy edits as I’m writing a first draft. But I do go over my previous day’s work for style and obvious fixes. So come back to your scene the next day, or at least after a time away from it, and keep the following in mind as you edit:

Check all adverbs with a loaded pencil

If an adverb can be cut without losing anything (which is usually the case) cut it. Strive for a stronger verb instead. He shuffled across the room is better than He walked slowly across the room.

Check all adjectives

First, ask if they’re necessary. Test them. Sometimes cutting them makes the description more immediate.

But adjectives are in our language for a reason. If you keep them, see if you can make them more vivid. Icy may be better than cold, etc.

Beef up what’s soggy

You may find a spot that needs more descriptive power. Here’s what I do in such a case. I write [MORE] in that spot then open up a blank TextEdit document. I like using TextEdit because it doesn’t feel “permanent” and I can play around. I’ll take several minutes to explore the moment, writing fast and loose, and then I’ll look it over and choose what I like. It may be just one line, or even one word. But if it’s the right line or word, the exercise is well worth it.

You don’t always have to describe a setting at the beginning of a scene

Vary where you put the description. At the top is fine, but sometimes get into the action first. Or start with dialogue. Then drop in the setting description. Readers won’t mind waiting if something interesting is going on.

You don’t have to describe everything at once

You can dribble in bits of description as you go along. This is especially effective as the intensity of the scene increases. Your POV character can notice something that wasn’t evident before, in keeping with the tone of the scene. Hemingway did this famously in his story “Soldier’s Home,” when the young man back home after World War I is feeling hectored at breakfast by his worried mother. Krebs looked at the bacon fat hardening on his plate.

Know when less is more, and when more is more

Deciding how much description to use for a setting is not a matter of formula. But here’s a little tip that will help: the more intense the emotions inside the character, the more you include in description.

For example, in an opening scene where the character is not yet in the hot crucible of conflict, maybe the description is brief. The first scene in Lawrence Block’s story, “A Candle for the Bag Lady,” has Matthew Scudder sitting in Armstrong’s, a bar. He describes it this way:

The lunch crowd was gone except for a couple of stragglers in front whose voices were starting to thicken with alcohol.

Block leaves it at that, because this is “normal” Scudder. He’s not feeling anything intensely yet.

But later, as Scudder is trying to find out who brutally murdered Mary Alice Redfield –– the “shopping bag lady” who inexplicably left him a sum of money in her will –– he investigates her last known residence:

Mary Alice Redfield’s home for the last six or seven years of her life had started out as an old Rent Law tenement, built around the turn of the century, six stories tall, faced in red-brown brick, with four apartments to the floor. Now all of those little apartments had been carved into single rooms as if they were election districts gerrymandered by a maniac. There was a communal bathroom on each floor and you didn’t need a map to find it.

So there you have it, friends. With a little thought and planning, you can turn run-of-the-mill descriptions into moments of stylistic magic. That’s the kind of writing that gets rewarded with word-of-mouth and future purchases.

So what is your approach to description?

What authors do you admire who do it well?