By PJ Parrish

The opening line of your book is the single hardest line you write.

Many writers would disagree with that. But for my money, those writers are:

A. those lucky devils for whom all things come easy;

B. those diligent do-bees who can scribble down anything just to get started and then go back and rewrite or

C. those types who aren’t really very good at what they do or maybe are just phoning it in.

Yeah, C is probably a little harsh. But I truly believe this. I have great respect and envy for writers who create wonderful openings and I also little regard for those who never even try. And can’t we all tell the difference?

I am not talking about “hooks.” I’m talking about those rare and glorious opening moments in stories that are telling us, “OO-heee, something special is about to happen here!” Hooks? I am firmly of the mind that anyone can write a decent hook. You’ve seen them, those clever one-liners tossed out by wise-ass PIs, those archly ironic first-person soliloquies, those purple-prose weather reports that substitute for mood.

We crime writers talk a lot about great hooks and how to get our readers engaged in the first couple pages. We worry about whether we should throw out a corpse in the first chapter, whether one-liners are best, if readers attention spans are too short for a slow burn beginning. This is especially true if you are writing what we categorize as “thrillers.”

But I’m tired of hooks. I’m thinking that the importance of a great opening goes beyond its ability to keep the reader just turning the pages. A great opening is a book’s soul in miniature. Within those first few paragraphs — sometimes buried, sometimes artfully disguised, sometimes signposted — are all the seeds of theme, style and most powerfully, the very voice of the writer herself.

It’s like you whispering in the reader’s ear as he cracks the spine and turns to that pristine Page 1: “This is the world I am taking you into. This is what I want to tell you. You won’t understand it all until you are done but here is a hint, a taste, of what I have in store for you.”

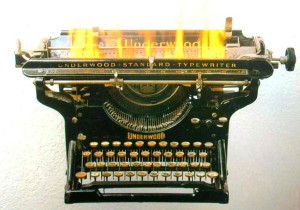

Which is why, today I am still staring at the blank page. We turned in our book last week to our new publisher and now it’s time to start the whole process all over again. I give myself a week off but then I try to get right back in the writing groove. I have an idea for a new book but that great opening?

Nothing has come to me yet. And I know my writer-self well enough by now that I know can’t move forward until I find just the right key to unlock what is to come. So here I sit, staring at the blinking curser, thinking that if I can only make good on my beginning’s promise, everything else will follow. Because that is what a great opening is to me: a promise to my reader that what I am about to give them is worth their time, is something they haven’t seen before, something that is…uniquely me.

Oh hell, I’ll let Joan Didion explain it. I have a feeling she’s given this a lot more thought than I have:

Q: You have said that once you have your first sentence you’ve got your piece. That’s what Hemingway said. All he needed was his first sentence and he had his short story.

Didion: What’s so hard about that first sentence is that you’re stuck with it. Everything else is going to flow out of that sentence. And by the time you’ve laid down the first two sentences, your options are all gone.

Q: The first is the gesture, the second is the commitment.

Didion: Yes, and the last sentence in a piece is another adventure. It should open the piece up. It should make you go back and start reading from page one. That’s how it should be, but it doesn’t always work. I think of writing anything at all as a kind of high-wire act. The minute you start putting words on paper you’re eliminating possibilities.

Didion gave this interview around the time she published her great memoir after her husband’s death The Year of Magical Thinking, the first line of which is: “Life changes fast.”

Here are some more openings I really love:

I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974.

That’s from Jeffrey Eugenides’s Middlesex. To me, it’s magic, because there in that one deceivingly simple declarative sentence lies the all tenderness, irony and roiling epic scope of his story.

And then there’s this one:

The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call “out there.”

That’s from Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. This is the first line of a long paragraph of description that opens the book, yet look at what it accomplishes — puts us down immediately in his setting, conveys the book’s bleak mood and hints with those two words “out there” that he is taking us to an alien place where nothing makes sense (the criminal mind).

And here is the one I always bring up:

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta..

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry (out of envy) when I read that one.

What is so terrifying about openings, I suppose, is that you only have so much space to work with: the first line, the first paragraph, that’s it. Because once you’ve moved deeper into that first chapter, that golden moment of anticipation is gone and then you the writer are busily engaging all the gears to move the reader onward. The opening is the moment before the kiss; the rest is relationship. And you only have precious seconds to make a good impression.

I read a lot of crime novels. I do this to keep up with what’s going on in our business but I also do it out of pleasure. But it seems to me that lately I am reading too many genre books that just aren’t trying hard enough, and you really can see it in the openings. Maybe this has something to do with the pressure to put out a book a year. Maybe I am reading the wrong people. But I find myself wishing for less “hook” and more artfulness.

That said, I pulled a couple books from my crime shelf and found some “oldies” that I like:

We were about to give up and call it a night when somebody dropped a girl off the bridge. — John D. MacDonald, Darker Than Amber

They threw me off the hay truck about noon. — James M. McCain, The Postman Always Rings Twice

The girl was saying goodbye to her life. And it was no easy farewell. — Val McDermid, A Place of Execution.

Not bad for one-liners. Then there are the more measured openings:

Death is my beat. I make my living from it. I forge my professional reputation on it. I treat it with the passion and precision of an undertaker – somber and sympathetic about it when I’m with the bereaved, a skilled craftsman with it when I’m alone. I’ve always thought the secret of dealing with death was to keep it at arm’s length. That’s the rule. Don’t let it breathe in your face. But my rule didn’t protect me.

That’s from my favorite Mike Connelly book, The Poet, and it works because it succinctly captures his protagonist’s voice and the theme of the story.

There is a bullet in my chest, less an a centimeter from my heart. I don’t think about it much anymore. It’s just a part of me now. But every once in a while, one a certain kind of night, I remember that bullet. I can feel the weight of it inside me. I can feel its metallic hardness. And even though that bullet has been warming inside my body for fourteen years, on a night like this when it is dark enough and the wind is blowing, that bullet feels as cold as the night.

Lovely writing from Steve Hamilton. See how the bullet, the setting and the key point of Alex McKnight’s backstory coalese around theme?

These are writers who understand the difference between a hook and an opening. They declare their authority as master storytellers right from the start. When a writer presents me with an opening like this…well, I would follow them anywhere.