by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

The outskirts of Flagstaff, Arizona. I was with my high school church group, taking a week in the summer  to do volunteer work for the Hopi. Our bus had stopped for the night and we brought our sleeping bags and duffels into the fellowship hall of a local church. We were told by our adult leaders to relax, read, play games, listen to the radio––but by all means stay inside the hall! Which of course my friend Randy and I interpreted as meaning: “Feel free to wander into town and find some trouble to get into.”

to do volunteer work for the Hopi. Our bus had stopped for the night and we brought our sleeping bags and duffels into the fellowship hall of a local church. We were told by our adult leaders to relax, read, play games, listen to the radio––but by all means stay inside the hall! Which of course my friend Randy and I interpreted as meaning: “Feel free to wander into town and find some trouble to get into.”

Ever ready to follow instructions as we understood them, Randy and I slipped out the side doors and started a nocturnal tour of the bustling Flagstaff metropolis, which seemed to have, as they used to say, rolled up the sidewalks.

So we walked and talked and came to a railroad crossing, moving therefrom into the soft red-and-yellow neon of a LIQUOR STORE sign. To a couple of seventeen-year-olds on a nighttime prowl, such illumination is catnip. Randy suggested we baptize our adventure with a bottle.

I agreed, as Randy Winter was my brother from another mother, my closest friend, with whom I laughed much and talked deeply. We would discuss with equal fervor the mystery of girls and the character of God (whose reputation, by the way, we were failing to uphold as we schemed how to lay our hands on some demon intoxicant).

Our first order of business was what manner of spirits to acquire. As an athlete who was not a member of the party circuit, I was not an imbiber of any sort. I did not like the taste of beer. I’d snuck a nip of gin once in my parents’ liquor cabinet and wondered why on earth anyone would want to drink gasoline.

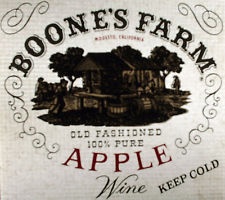

So Randy suggested we try some wine. He’d heard that Boone’s Farm Apple Wine went down nicely, and the decision was made.

Then the next step: to lurk in the shadows of the parking lot until a car drove up, then casually approach the driver with a request that he be our procurer. This was nervous time, for who knew what kind of personality we would engage? What if it was an off-duty cop? Or some old Veteran of Foreign Wars who’d want to lecture us on the evils of drink?

A chance we would have to take. Which we did presently when a car drove in, and out stepped a man of about thirty, with long hair. Long hair! A good sign. A hippie perhaps, or at least a musician. In either case, cool. We emerged from our hiding spot and said, “Excuse me …”

The man stopped and read our faces in the soft, primrose light. “You want me to get you a bottle, don’t you?” he said.

We nodded. My face felt flush, as if the entire world were witnessing my iniquity.

The man laughed. “I used to do the same thing. What do you want?”

We gave the man a couple of fins, our pooled resources, and Randy said, “Boone’s Farm Apple Wine.”

It seemed to me the man hesitated, as if to give us one last chance to reconsider our fate. And then he went through the door.

Randy and I high-fived our success. And soon thereafter we had in our hands a brown paper bag and some change, passed to us with a “Good luck” sentiment from our partner in crime.

We left the scene of our misdemeanor, went back near the railroad tracks, and sat cross-legged on the ground.

Randy unscrewed the top. We were too unsophisticated to smell the cap.

Then he drank and passed the bottle to me. I took a tentative sip. Ah, I thought. Sprightly, with a conversational fruitiness and subdued notes of summer. (Actually, what I really thought was, This isn’t so bad.)

And so ‘neath the Arizona stars Randy Winter and I shared a bottle of what was generously classified as wine, and discovered something interesting about the human body, namely, that there is a lag time between the ingestion of alcoholic content and its effect on one’s physiology.

Which meant, at one point, it suddenly felt as if a switch was flipped in my brain. The disco ball lit up and went round and round, and I heard myself say something like, “Rammy, my headth pinning” before I teetered backward and ended up on the gravel, looking up at the stars as they raced around the heavens like sparkling emergency room nurses shouting, “Stat! Stat!”

Which is the last thing I remember about that night. In the morning I was in my sleeping bag on the church floor. At least I think it was my sleeping bag. My stomach felt like a balloon of toxic gasses. Two miniature railroad workers were on either side of my head, driving spikes into my temples with their sledgehammers.

The adult leaders were none too pleased with Randy and me. We knew we’d messed up, crossed the line, failed to represent our church. We were threatened with expulsion, which would mean a long and humiliating drive for our parents to come pick us up. We threw ourselves upon the mercy of the court and were granted a temporary stay. I began then to truly appreciate the power of forgiveness. Plus, I was ready to swear off booze for good.

Honest, hard work kept Randy and me on the straight and narrow for at least a week. There’s a victory in there somewhere.

I don’t know why I’m writing about this now, except that I was thinking about Randy the other day, as I do often. He died at the age of nineteen. Leukemia. When I think about him, and all the good times we had, this particular memory is the one that surfaces first.

Why is that? Maybe because it typified our friendship. We took risks together, got in trouble on occasion, but mostly laughed. A couple of times there were tears. There’s something deeply meaningful to me in all this, and if I explore it I sense it will tell me something about what I write and why. It may also be a story idea trying to get out.

Memories are the deep soil of strong fiction. We do well to work that land from time to time. Journal about it. Record it. Listen to it.

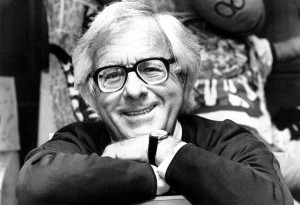

Early in his career Ray Bradbury started making lists of nouns, many of them based on childhood memories. Things like The Lake, The Night, The Crickets, The Ravine.

“These lists were the provocations,” he writes in Zen in the Art of Writing, “that caused my better stuff to surface. I was feeling my way toward something honest, hidden under the trapdoor on the top of my skull.”

Open up your own trapdoor. You’ll get to really good stuff that way. You can use it outright as the basis for a piece of fiction, or tap it for characters, emotions, scenes. Nothing is wasted. All of life is material.

And it will teach you, too, if you’re open. For I don’t believe I’ve had a taste of Boone’s Farm wine since that night. Nothing against it, you understand, but I prefer a nice California cab. In fact, I think I’ll have a glass tonight––just one––and raise a toast to my best friend, Randy Winter.

What about you? What friend from your youth do you remember, and why?

The act of writing is, for me, like a fever — something I must do. And it seems I always have some new fever developing, some new love to follow and bring to life. – Ray Bradbury