by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

If you ever find yourself among a group of writers, writing teachers, agents or editors; and said group is waxing verbose on the craft of fiction; and the subject of what fiction is or should be rumbles into the discussion, you are likely to hear things like:

If you ever find yourself among a group of writers, writing teachers, agents or editors; and said group is waxing verbose on the craft of fiction; and the subject of what fiction is or should be rumbles into the discussion, you are likely to hear things like:

All fiction is character-driven.

It’s characters that make the book.

Readers care about characters, not plot.

Don’t talk to me about plot. I want to hear about the characters!

Such comments are usually followed by nods, murmured That’s rights or I so agrees, but almost never a healthy and hearty harrumph.

So, here is my contribution to the discussion: Harrumph!

Now that I have your attention, let me be clear about a couple of items before I continue.

First, we all agree that the best books, the most memorable novels, are a combination of terrific characters and intriguing plot developments.

Second, we all know there are different approaches to writing the novel. There are those who begin with a character and just start writing. Ray Bradbury was perhaps the most famous proponent of this method. He said he liked to let a character go running off as he followed the “footprints in the snow.” He would eventually look back and try to find the pattern in the prints.

Other writers like to begin with a strong What if, a plot idea, then people it with memorable characters. I would put Stephen King in this category. His character work is tremendous. Perhaps that is his greatest strength. But no one would say King ignores plot. He does avoid outlining the plot. But that’s more about method.

I’m not talking about method.

What I am proposing is that no successful novel is ever “just” about characters. In fact, no dynamic character can even exist without plot.

Why not? Because true character is only revealed in crisis.

Without crisis, a character can wear a mask. Plot rips off the mask and forces the character to transform––or resist transforming.

Now, what is meant by a so-called character-driven novel is that it’s more concerned with the inner life and emotions and growth of a character. Whereas a plot-driven novel is more about action and twists and turns (though the best of these weave in great character work, too). There is some sort of indefinable demarcation point where one can start to talk about a novel being one or the other. Somewhere between Annie Proulx and James Patterson is that line. Look for it if you dare.

We can also talk about the challenge to a character being rather “quiet.” Take a Jan Karon book. Father Tim is not running from armed assassins. But he does face the task of restoring a nativity scene in time for Christmas. If he didn’t have that challenge (with the pressure of time, pastoral duties, and lack of artistic skills) we would have a picture of a nice Episcopal priest who would overstay his welcome after thirty or forty pages. Instead, we have Shepherds Abiding.

If you still feel that voice within you protesting that it’s “all about character,” let me offer you this thought experiment. Let’s imagine we are reading a novel about an antebellum girl who has mesmerizing green eyes and likes to flirt with the local boys.

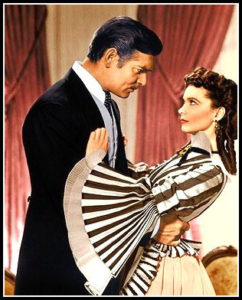

Let’s call her, oh, Scarlett.

We meet her on the front porch of her large Southern home chatting with the Tarleton twins. “I just can’t decide which of you is the more handsome,” she says. “And remember, I want to eat barbecue with you!”

Ten pages later we are at an estate called Twelve Oaks. Big barbecue going on. Scarlett goes around flirting with the men. She also asks one of her friends who that man is who is giving her the eye.

“Which one?” her friend says.

“That one,” says Scarlett. “The one who looks like Clark Gable.”

“Oh, that’s Rhett Butler from Charleston. Stay away from him.”

“I certainly will,” says Scarlett. (The character of Rhett Butler never appears again.)

Scarlett then finds Ashley Wilkes and coaxes him into the library.

“I love you,” she says.

“I love you too,” Ashley says. “Let’s get married.”

So they do.

One hundred pages later, Scarlett says, “I really do love you, Ashley.”

Ashley says, “I love you, Scarlett. Isn’t it grand how wonderful our life is?”

At which point a reader who has been very patient tosses the book across the room and says, “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

What’s missing? Challenge. Threat. Plot! In the first few pages Scarlett should find out Ashley is engaged to another woman! And then she should confront him, and slap him, and then break a vase over the head of that scalawag who looks like Clark Gable! Oh yes, and then a little something called the Civil War needs to break out.

These developments rip off Scarlett’s genteel mask and begin to show us what she’s really made of.

That is what makes a novel.

Yes, yes, you must create a character the readers bond with and care about. But guess what’s the best way to do that? No, it’s not backstory. Or a quirky way of talking. It’s by disturbing their ordinary world.

Which is a function of plot.

So don’t tell me that character is more important than plot. It’s actually the other way around. Thus:

- If you like to conceive of a character first, don’t do it in a vacuum. Imagine that character reacting to crisis. Play within the movie theater of your mind, creating various scenes of great tension, even if you never use them in the novel. Why? Because this exercise will begin to reveal who your character really is.

- Disturb your character on the opening page. It can be anything that is out of the ordinary, doesn’t quite fit, portends trouble. Even in literary fiction. A woman wakes up and her husband isn’t in their bed (Blue Shoe by Ann Lamott). Readers bond with characters experiencing immediate disquiet, confusion, confrontation, trouble.

- Act first, explain later. The temptation for the character-leaning writer is to spend too many early pages giving us backstory and exposition. Pare that down so the story can get moving. I like to advise three sentences of backstory in the first ten pages, used all at once or spread around. Then three paragraphs of backstory in the next ten pages. Try this as an experiment and see how your openings flow.

- If you’re writing along and start to get lost, and wonder what the heck your plot actually is, brainstorm what may be the most important plot beat of all, the mirror moment. Once you know that, you can ratchet up everything else in the novel to reflect it.

Do these things and guess what? You’ll be a plotter! Don’t hide your face in shame! Wear that badge proudly!

As always, a great post. One of my first lessons was “only trouble is interesting.” At a romance conference, it was “Put your heroine up a tree and shoot at her.”

Of course, if your readers don’t care about the characters, then they won’t care about what trouble is raining down on them, or if they get shot out of the tree.

I’m not an ‘in advance’ plotter, but I do try to start with a character’s conflict, but I also end up cutting my opening scenes, which tend to have too much back story no matter how many times I tell myself that “this time, I’m going to start in the right place.” As long as you’re not afraid to use the delete key, I think you can start anywhere if it helps you know your characters.

In fact, I’ve included one of those ‘false start’ scenes for my current WIP in my newsletter.

Of course, if your readers don’t care about the characters, then they won’t care about what trouble is raining down on them, or if they get shot out of the tree.

I’d say if you get them up a tree with all dispatch, the caring is by default…but you can stop the caring by flubbing the character’s responses. Remember how audiences reacted to Kate Capshaw in Temple of Doom?

Terry… “only trouble is interesting”… you’ll be interested in my KZ post tomorrow. So much so you’ll think you actually inspired it with your comment today on Jim’s terrific post. We’re already on the same page, as you’ll see. – Larry

Looking forward to reading it.

Jim, thanks for another great post.

Using the mirror moment early in the planning stage has truly helped me know where I’m going with the story. It’s also given me success with short stories.

The only downside to focusing on the mirror moment: If you watch movies with your spouse, they will become tired of you glancing at the clock, then stating authoritatively, “Yes, that’s the mirror moment.”

Have a great Labor Day weekend!

Funny, Steve. When I was writing the book Mrs. B and I watched the Costner movie No Way Out. At one point I felt “it” (the moment) about to happen. I paused the DVD. Looked at the counter. Exactly half way.

Cindy turns to me and says, “Why’d you pause? This isn’t about the mirror thing, is it?”

I said, “You are about to see what a genius your husband is. Kevin is about to have his mirror moment.”

I had no idea what was coming next. But there it was. Costner lunges into a bathroom with stunning, reversal news, and … looks at himself in the mirror.

Now, it’s my wife who keeps asking, “Is this it? Is this the mirror moment?”

I love her.

Sorry to continue an off-topic thread, but I was watching a new BBC drama about the young Queen Victoria, who had to overcome a lot of opposition to secure her reign. About halfway through, when things were looking quite bleak, she actually looked into a mirror. And I turned to my wife and said, “She’s having her mirror-moment.” I did credit you, though.

Love it! It’s funny, I keep seeing actual mirrors used for this in classic movies. Now, Voyager is one. I saw one in a Robert Ryan movie a year or so ago. I think it was Day of the Outlaw.

I always smile.

Plot is to character what the super collider is to atomic particles. The collider stresses particles at high speeds to force them to reveal their secrets.

Love that analogy, Mike! Especially about revealing secrets. That’s always a nice move in a plot.

Great post, Jim, as usual.

I once heard an old woman say, “A brook can’t sing until it runs over rocks.”

I’ve never forgotten that.

Boy, love that analogy, Dave. It applies to life, too!

Thank you, Sir, for another helpful posting ~

Lately I’ve found myself reading one or the other of the above~ characters I like, but to whom nothing happens, or inyriguing situations with nobody in the I much care for~ and finishing neither.

I like the “3-in-10/3-in-the-next-10” rule of thumb~ read it before/can’t read it enough.

g

Thanks, George. You mention two types of books here. While I think it’s almost impossible to write a popular book with character and no plot, there are many examples of plot-heavy books with thin characterizations. I mean, heck, the Executioner (Mac Bolan) series has sold something north of 200 million copies! And most of these can be encapsulated as: Mac Bolan gathers a lot of military-grade weapons, kills a whole bunch of the mafia (or commies, or terrorists …) and goes on to the next book.

“Other writers like to begin with a strong What if, a plot idea, then people it with memorable characters. I would put Stephen King in this category.”

This is me–although I haven’t yet earned the right to use “memorable” in regards to my characters–I’m working on that. 😎 But I always have plot first, than develop the characters, especially since most of my ideas come from research.

The biggest problem I have in dealing with characters is that in real life, lives are complex and often filled with contradictions, and the situations in our life often mean we spin our wheels (add to that my protag is in the frontier army—things don’t always move fast in the army). But when you write a story, trying to make characters seem like real life leaves the reader confused about the character’s goals and maybe not quite attached and yes–if I’m not careful, I forget to leave out the parts readers like to skip. But it just isn’t so easy to do that if you’re trying to make characters more than one dimensional.

I shall be curious if at any point in my writing life I ever do a Bradbury and do a character first and start following them. It would certainly be a big change of approach.

But when you write a story, trying to make characters seem like real life leaves the reader confused about the character’s goals and maybe not quite attached and yes–if I’m not careful, I forget to leave out the parts readers like to skip.

You hit on a great issue, BK. How “real” do we make our characters without going over-Freud on our readers? We often talk about “three dimensional” characters, but that may be misleading if we try to make it three contradictory personality traits. Two, deeply explored, is probably much better. It’s sort of like Stein’s description formula of 1 + 1 = 1/2, where if you have one strong image, adding another next to it dilutes the description. It doesn’t strengthen it.

Thus, for characters (and you got me to think of it just now, BK), perhaps it’s 1 + 1 + 1 = 1/2. Whereas 1 + 1 = 3 or 4.

We’re not rendering “real life.” We’re giving the illusion of life for a fictional purpose.

There was a t.v. series called Monk. Monk was a detective with a lot of phobias. He was very interesting. I can see how starting with a character like him and then thinking up plots to show off his character would work very well.

Thanks for this one Jim. I entirely agree. I think of plot as a wet fish that continuously slaps the protagonist in the face. To some degree, I actually plan (or plot) a story this way. I’ve got this sort of character floating around. And I’ve got this sort of story leaking out of another dimension. But I develop the two more or less independently. Then I apply the plot to the character. If I’ve developed the character sufficiently, then I get to see how each plot event forces him to react. The only fly in the ointment is trying to build a classic character arc or story arc. That takes a little maneuvering in the middle. But the tension and suspense is already built in.

Well, Stephen, when it comes to the middle, I’m your man.

I like the wet fish analogy. You can take it further. In a “quiet” plot, the fish is a minnow. It’s still unpleasant to get slapped with one.

Or the fish could be a piranha….

Thank you for giving us back stories.

As an English major undergrad, I grew weary of writing papers on, reading commentaries one, reading analyses on, and hearing lecture after lecture on, characters. Great characters. Bold characters. Characters of meekness and humble retreat. Characters of jauntiness and integrity and great scope.

I was being in my education and reading, driven into that horrid place of that character whose name I can’t remember in the book I can’t remember (seems as if it was all Dickens), who urged everybody to “read for style. Only for style.” Don’t enjoy the story. Don’t remember the characters. Style.

Well, there I was. Character. Only character.

Then, one day, I remembered that I enjoyed stories. Stories contained characters.

My ultimate rebellion against the proffered wisdom of priority of character was, “Hey. What happens next?”

Love that, Jim. Readers, to, get tired of characters just killing time (the reader’s time!)

As Dean Koontz put it so directly in Writing Bestselling Fiction: “Never forget that the reader just wants to GET ON WITH IT!”

If I may… I’ve found myself saying EXACTLY those four words here recently… With maybe an additional “C’mon…” thrown in out of sheer frustration…

You and BK are killing me. I became a writer because I hate math!

I never understood how people separated character and plot. Your Gone with the Wind example was perfect. Scarlett isn’t interesting without conflict, and the many conflicts that occur in the novel mean nothing without a compelling character to experience them and try to rise above them.

And I’m with Jim on this one… comp papers in college became tedious, almost to the point of me reconsidering my career path. I’m glad I didn’t (like I said earlier, getting a master’s degree in math was never in the cards), but it is refreshing to find someone who realizes character and plot have a synergy that creates a better story.

Staci, I fear that many a comp or lit class in high school or college nipped a promising writing career in the bud.

OTOH, Flannery O’Connor was once asked if she thought universities stifled writers. She said, “My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them.”

LOL. That’s great!

When I’m thinking of reading a novel, I ask, WHAT is this story about? I don’t ask WHO is this story about, unless it is a biography.

To tell someone what a story is about you need to tell about a person (or a stand in for a person) and plot events. “An old man did this and this and then this happened, the end.”

Exactly, Augustina. Even among those who champion character-driven stories or movies, if you ask them what the story is about, it’s always about a character WHO _____.

Once again you and I are operating from the same playbook. When you see my post tomorrow, you’ll see why some might think we conspired to create a two-part series. Which Terry is already shadowing in her comment above.

I preach this message constantly. Well stated here, Jim.

Well, it’s that “great minds” cliche. Of course, cliches are always based in truth…

Looking forward to your post!

You break things done so wonderfully!!

Thanks, Traci. You know, that’s really it. I do try to “pop the hood” and take things apart, and show writers how to put it all together again.

I probably could have helped poor old Humpty…

In “Emotional Structure: Creating the Story Beneath the Plot,” Peter Dunne writes: “The story is the journey for truth. The plot is the road it takes to get there.” He also writes: “A character’s “emotional through-line, the emotional structure is the first story to be developed deeply. Only then can the plot be developed to serve it.” In his view, plot serves the characters, rather than the other way around.

While I understand his way of thinking, I believe that character arc and plot are intricately intertwined. I always start with a concept, but my plot definitely evolves as I spend more time with my characters. So, how does one marry plot structure with character arc? Michael Hauge and Christopher Vogler have a DVD that I recommend entitled “The Hero’s Two Journeys.” Good stuff.

As far as story openings go, I do believe that a story should start with some kind of disturbance to the hero’s ordinary world. It wouldn’t be very interesting to watch a character brush his teeth in the morning, for example. One doesn’t have to go overboard, but something unexpected should happen. For a good example, watch the opening to the movie “Erin Brokovich.”

Great topic, btw!

Some good resources mentioned there, GR. I do love the word “unexpected.” That’s almost the definition of good plotting.

I have quite a few of your books sitting on my shelf, as well, btw. The pages are worn!

Well said Jim.

For all of my books thus far I always first have a vision of the main character in some scenario (a crash landed shuttle pilot, a man relaxing by a woodstove in rural Alaska, a pastor with a .45 pistol hidden in the pulpit, a dad dropping his kids off at scout camp, a man in medieval Ireland finds an old chest under a storm fallen tree) but then the thought presses, “What happens next” ie, what is the plot to this guy’s life and how it is going to help him through whatever S#!T storm is just around the corner?

Indeed, Basil. Make it a “storm.” Hold back nothing!

(Least of all leprechauns…)

Pingback: Top Picks Thursday! For Readers and Writers 09-08-2016 | The Author Chronicles