by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

If you ever find yourself among a group of writers, writing teachers, agents or editors; and said group is waxing verbose on the craft of fiction; and the subject of what fiction is or should be rumbles into the discussion, you are likely to hear things like:

If you ever find yourself among a group of writers, writing teachers, agents or editors; and said group is waxing verbose on the craft of fiction; and the subject of what fiction is or should be rumbles into the discussion, you are likely to hear things like:

All fiction is character-driven.

It’s characters that make the book.

Readers care about characters, not plot.

Don’t talk to me about plot. I want to hear about the characters!

Such comments are usually followed by nods, murmured That’s rights or I so agrees, but almost never a healthy and hearty harrumph.

So, here is my contribution to the discussion: Harrumph!

Now that I have your attention, let me be clear about a couple of items before I continue.

First, we all agree that the best books, the most memorable novels, are a combination of terrific characters and intriguing plot developments.

Second, we all know there are different approaches to writing the novel. There are those who begin with a character and just start writing. Ray Bradbury was perhaps the most famous proponent of this method. He said he liked to let a character go running off as he followed the “footprints in the snow.” He would eventually look back and try to find the pattern in the prints.

Other writers like to begin with a strong What if, a plot idea, then people it with memorable characters. I would put Stephen King in this category. His character work is tremendous. Perhaps that is his greatest strength. But no one would say King ignores plot. He does avoid outlining the plot. But that’s more about method.

I’m not talking about method.

What I am proposing is that no successful novel is ever “just” about characters. In fact, no dynamic character can even exist without plot.

Why not? Because true character is only revealed in crisis.

Without crisis, a character can wear a mask. Plot rips off the mask and forces the character to transform––or resist transforming.

Now, what is meant by a so-called character-driven novel is that it’s more concerned with the inner life and emotions and growth of a character. Whereas a plot-driven novel is more about action and twists and turns (though the best of these weave in great character work, too). There is some sort of indefinable demarcation point where one can start to talk about a novel being one or the other. Somewhere between Annie Proulx and James Patterson is that line. Look for it if you dare.

We can also talk about the challenge to a character being rather “quiet.” Take a Jan Karon book. Father Tim is not running from armed assassins. But he does face the task of restoring a nativity scene in time for Christmas. If he didn’t have that challenge (with the pressure of time, pastoral duties, and lack of artistic skills) we would have a picture of a nice Episcopal priest who would overstay his welcome after thirty or forty pages. Instead, we have Shepherds Abiding.

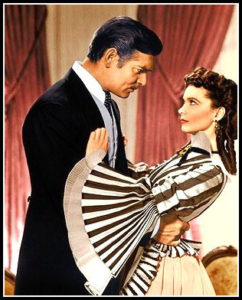

If you still feel that voice within you protesting that it’s “all about character,” let me offer you this thought experiment. Let’s imagine we are reading a novel about an antebellum girl who has mesmerizing green eyes and likes to flirt with the local boys.

Let’s call her, oh, Scarlett.

We meet her on the front porch of her large Southern home chatting with the Tarleton twins. “I just can’t decide which of you is the more handsome,” she says. “And remember, I want to eat barbecue with you!”

Ten pages later we are at an estate called Twelve Oaks. Big barbecue going on. Scarlett goes around flirting with the men. She also asks one of her friends who that man is who is giving her the eye.

“Which one?” her friend says.

“That one,” says Scarlett. “The one who looks like Clark Gable.”

“Oh, that’s Rhett Butler from Charleston. Stay away from him.”

“I certainly will,” says Scarlett. (The character of Rhett Butler never appears again.)

Scarlett then finds Ashley Wilkes and coaxes him into the library.

“I love you,” she says.

“I love you too,” Ashley says. “Let’s get married.”

So they do.

One hundred pages later, Scarlett says, “I really do love you, Ashley.”

Ashley says, “I love you, Scarlett. Isn’t it grand how wonderful our life is?”

At which point a reader who has been very patient tosses the book across the room and says, “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

What’s missing? Challenge. Threat. Plot! In the first few pages Scarlett should find out Ashley is engaged to another woman! And then she should confront him, and slap him, and then break a vase over the head of that scalawag who looks like Clark Gable! Oh yes, and then a little something called the Civil War needs to break out.

These developments rip off Scarlett’s genteel mask and begin to show us what she’s really made of.

That is what makes a novel.

Yes, yes, you must create a character the readers bond with and care about. But guess what’s the best way to do that? No, it’s not backstory. Or a quirky way of talking. It’s by disturbing their ordinary world.

Which is a function of plot.

So don’t tell me that character is more important than plot. It’s actually the other way around. Thus:

- If you like to conceive of a character first, don’t do it in a vacuum. Imagine that character reacting to crisis. Play within the movie theater of your mind, creating various scenes of great tension, even if you never use them in the novel. Why? Because this exercise will begin to reveal who your character really is.

- Disturb your character on the opening page. It can be anything that is out of the ordinary, doesn’t quite fit, portends trouble. Even in literary fiction. A woman wakes up and her husband isn’t in their bed (Blue Shoe by Ann Lamott). Readers bond with characters experiencing immediate disquiet, confusion, confrontation, trouble.

- Act first, explain later. The temptation for the character-leaning writer is to spend too many early pages giving us backstory and exposition. Pare that down so the story can get moving. I like to advise three sentences of backstory in the first ten pages, used all at once or spread around. Then three paragraphs of backstory in the next ten pages. Try this as an experiment and see how your openings flow.

- If you’re writing along and start to get lost, and wonder what the heck your plot actually is, brainstorm what may be the most important plot beat of all, the mirror moment. Once you know that, you can ratchet up everything else in the novel to reflect it.

Do these things and guess what? You’ll be a plotter! Don’t hide your face in shame! Wear that badge proudly!