James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

because he’s dying of cancer and wants to provide for his wife and handicapped son.

So what character in recent fiction have you been drawn to, and why?

James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

because he’s dying of cancer and wants to provide for his wife and handicapped son.

Our first page reviews often bring up the issue of backstory and how to incorporate it successfully (and judiciously) into a novel.

In mysteries and thrillers we often have protagonists with a military or law enforcement background and, given that many of our readers will have similar backgrounds, we need to get the details right. As writers we have an obligation to do our research and try and paint as accurate a picture as possible. This can be a challenge for someone like me who has never been in the armed forces, trained in law enforcement, or (thankfully) had any exposure to war or its aftermath. I have to rely solely on research and my imagination.

So far in my novels, I’ve focused primarily on the years prior to and during the First World War and have the advantage of being able to access a huge array of first hand accounts, books, film footage and audio recordings dealing with the horrors associated with trench warfare. There are, however, only a minute number of veterans still alive from this war which means I cannot directly speak to them about their experiences as part of my research. In some ways though, this also makes my job a little easier, as there aren’t going to be many World War One veterans alive to challenge the experiences as I present them.

For more recent theatres of conflict, authors need to be ever vigilant regarding their research as there are many more veterans alive who will demand we get the details correct (and who will complain if we fail to do them justice). When it comes to developing a character with a recent military backstory, authors need to also be aware of the sensitivities involved – whether you’re dealing with a character who served in Afghanistan, a character involved in one side or the other during the Northern Ireland Troubles, or, perhaps, a CIA operative who had exposure to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict…whatever the backstory is you have to get it right.

As we’ve also discussed in our first page reviews, when presenting a character’s backstory you also have to be careful not to slow down the narrative pace of the book. All the details you have researched cannot be presented in huge, long-winded chunks, or your readers’ eyes will glaze over.

Here are a few tips when it comes to developing and presenting a compelling backstory:

When developing the backstory (particularly a military or law enforcement one):

When presenting the details of your protagonist’s backstory, remember:

So do you tend to have protagonists with a military or law enforcement background in your stories? If so, how do you go about researching this and what pitfalls do you try to avoid when presenting your character’s backstory?

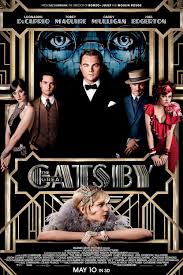

This weekend I saw Baz Luhrmann’s sumptuous, over the top, movie adaptation of The Great Gatsby and was reminded, yet again, of the power certain fictional names have on the psyche. Gatsby. Not a name one easily forgets. Neither is Heathcliff or Mr. Rochester or those great detective names: Sam Spade, Nero Wolfe, Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot. Even the most mundane sounding names can achieve prominence, simply because of their ordinariness (take Harry Potter for example). But naming a character is by no means an easy task. You have to balance the unusual with the commonplace and try to run the gauntlet between a cool, distinguished name and one that verges on being a soap-opera/porn name that you’d expect to see on somewhere like m porn xxx instead of a blockbuster Hollywood picture. So how do you come up with a memorable character name?

This weekend I saw Baz Luhrmann’s sumptuous, over the top, movie adaptation of The Great Gatsby and was reminded, yet again, of the power certain fictional names have on the psyche. Gatsby. Not a name one easily forgets. Neither is Heathcliff or Mr. Rochester or those great detective names: Sam Spade, Nero Wolfe, Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot. Even the most mundane sounding names can achieve prominence, simply because of their ordinariness (take Harry Potter for example). But naming a character is by no means an easy task. You have to balance the unusual with the commonplace and try to run the gauntlet between a cool, distinguished name and one that verges on being a soap-opera/porn name that you’d expect to see on somewhere like m porn xxx instead of a blockbuster Hollywood picture. So how do you come up with a memorable character name?

First and foremost it must reflect your character. I find this is a critical first step – finding a character name that reflects the character’s voice on the page. I’ve recently been revisiting an old WIP (finally having worked out the answer to a plot conundrum) and found myself weighing up two versions of the main protagonist’s name, trying them on to see which fit best. It’s a tricky process and one that has a cascading effect on other character names as well (as I can’t exactly have a cast of characters all with names starting with ‘M’!). But what other issues do authors need to pay attention to in naming characters? Here are a few:

So what about you all – what advice would you give fellow writers about coming up with terrific character names? What are are your favorite characters names? What about character names that set you teeth on edge?

Along with plot, setting, dialog, theme, and premise, your story is made up of characters. Hopefully, they’re interesting and believable. If they’re not, here are a few tips on making them so.

It’s important to think of your characters as having a life prior to the story starting, and unless you kill them off, also having a life beyond the last page. You need to know your character’s history. This doesn’t mean you have to explain every detail to the reader, but as the author, you must know it. Humans are creatures molded by our past lives. There’s no difference with your fictional characters. The more you know about them, the more you’ll know how they will react under different circumstances and levels of pressure.

The reader doesn’t need to know everyone’s resume and pedigree, but those things that happened to a character prior to the start of the story will help justify their actions and reactions in the story. For instance, a child who fell down a mine shaft and remained in the darkness of that terrible place for days until rescued could, as an adult, harbor a deep fear of cramped dark places when it comes time to deal with a similar situation in your story. Why does Indiana Jones stare down into the ancient ruins and hesitate to proceed when he says, “I hate snakes.” We know because he had a frightening encounter with snakes as a youth. But the background info must be dished out to the reader in small doses in order to avoid the dreaded “info dump”. Keep the reader on a need-to-know basis.

Next, realize that your characters drive your plot. If a particular character was taken out of the story, how would the plot change? Does a character add conflict? Conflict is the fuel of the story. Without it, the fire goes out.

Also remember to allow the reader to do a lot of the heavy lifting by building the characters in their mind. Give just enough information to let them form a picture that’s consistent with your intentions. The character they build in their imagination will be much stronger that the one you tried to over-explain. Telling the reader how to think dilutes your story and its strength. Don’t explain a character’s motives or feelings. Let the reader come to their own conclusion based upon the character’s actions and reactions.

Avoid characters of convenience or “messengers”. By that I mean, don’t bring a character on stage purely to give out information. Make your characters earn their keep by taking part in the story, not just telling the story.

Challenge your characters. Push them just beyond their preset boundaries. Make them question their beliefs and judgment. There’s no place for warm and cozy in a compelling story. Never let them get in a comfort zone. Always keep it just out of their reach.

And finally, make your characters interesting. Place contradictions in their lives that show two sides to their personality such as a philosophy professor that loves soap operas or a minister with a secret gambling addiction. Turn them into multi-faceted human beings in whom the reader can relate. Without strong characters, a great plots fall flat.

Keep your reader on a need-to-know basis and your characters on their toes to maintain suspense and a compelling read.

There are three kinds of writers: those who can count, and those who can’t. Also, those who like to fill out questionnaires or do extensive biographies of their main characters, and those who like to make up characters “on the fly” and flesh them out as they go along. So what is your preferred method for creating original and dynamic characters for your fiction?

by Jordan Dane

@JordanDane

On one of our first TKZ Reader Friday Posts, we asked for suggestions on posts you wanted to see. I went back to read a comment from TJC, a steadfast follower, and wanted to respond to this request:

I find the “first page” submissions and discussions informative and engaging. Any thought of other similar exercises, e.g. “character introductions”, “action scenes”, “backstory insertion” or other? ~tjc

I went back into our TKZ archives and found a post I did called “The Defining Scene – Character Intros,” but here are my thoughts on creating unforgettable characters.

Five Key Ways to Make Your Characters Memorable

1. Add Depth to Each Character—Give them a journey

2. Use Character Flaws as Handicaps

3. Clichéd Characters can be Fixed

4. Create A Divergent Cast of Characters

5. Flesh Out your Villains or Antagonists

Character Exercise: A great way to explore what makes a memorable character is to analyze ones you see on TV or in the movies. Pull apart the layers of the depth of their personalities, warts and all, and share some of your favorites. Describe a character you found unforgettable and tell us why.

I’ve been an avid reader since I was a kid in elementary school, but as I grew older, I wondered how authors concocted their stories and how much of their own experiences became a part of their fictional stories. Vivid scenes can put you into that moment with the characters. Exotic sights and smells can put you there, even if you’ve never been.

Now with each book that I write, I know the answer—at least for me. I feel like I’m treading on dangerous ground to reveal too much. I run the risk of pulling a reader out of my books because they may know where elements come from. But maybe telling some of my secrets might enrich a reader’s experience, like saying my stories are inspired by real headlines or true stories.

My first HarperCollins Sweet Justice series book, Evil Without A Face, had been inspired by a horrific near miss abduction by a young girl who had been virtually seduced online by a charming human trafficker. The girl had her computer only 6 months, a gift from her parents. The clever trafficker set up an elaborate scheme, involving innocent adults who he lied to, to trick this girl into leaving the US even when she didn’t have a passport. The FBI thwarted the abduction in Greece, minutes before the girl was to meet her kidnapper in a public market. The Echo of Violence (Sweet Justice #3) came from a real life terrorist plot to hold missionaries for ransom.

But those inspirations aren’t what I’m talking about. I’m referring to the small creative morsels that you pepper into your stories that are your secrets, no one else’s. So it’s confession time and I’ll start.

There’s a line in No One Heard Her Scream, my debut novel:

If she wanted to engage the only brain he had, all she had to do was unzip it and free willy.

I channeled that line through my character and didn’t even remember writing it, until one of my sisters asked about it. It came from one of my vacations when I visited Vancouver and took a day trip to see where they filmed “Free Willy.”

In my debut YA with Harlequin Teen, In the Arms of Stone Angels, I wrote about my 16-yr old Brenna Nash getting extra credit for dissecting a frog and earning extra credit for extracting the frog’s brain intact. Well, Brenna may have gotten the extra credit in the book, but I never did. I jabbed at that frog until it’s head was shredded. The brain popped out whole, so I asked for the credit. After my teacher saw the wreck I made, she only gave me a grimace and a heavy sigh. (There are quite a few more kid stories of mine in this book, but I’m stopping here.)

Sometimes I use real people that I know in my books as “fictional” characters. They know I’m doing it but they roll when they read what I wrote. I crack up too. The priest and Mrs Torres at the end of The Echo of Violence, for example. Yep, people I know. One of my favorite book reviewers for my YA novels entered a contest of mine and won being named a character in my upcoming release – Indigo Awakening. O’Dell shared some of his quirks in an email and after seeing that list, I thought he would make an odd villain. He can’t wait to read the book.

So now that I’ve given you a peek behind the curtain of Oz, is there anything you care to share about your own writing? If you’re a reader, have you ever heard or read stories about what elements have been connected to the real life of an author?

Have you ever met a person who is so interesting that you had to incorporate him into a story?

We’ve just returned from a one week cruise on Allure of the Seas. My review and photos can be followed on my personal blog. It was a fabulous trip on the largest cruise ship in the world. But despite its size, we often ran into the same people.

We first saw the man at dinner. Although we had My Time Dining, we’d reserved a spot at 5:45 in the Adagio Dining Room, deck 5, each evening. My startled gaze landed on the guy as we passed him by seated at a table with a younger man.

His shoulder-length wiry black hair inevitably drew my attention. He had a black moustache to match that curved down to the edges of his mouth. His dark eyes and facial features were Asian. My imagination instantly pegged him as a karate master. Was that his young disciple with him? The younger guy had light brown hair in a short cut with sideburns and looked like some fellow you’d meet on the street in the States. A more unlikely couple couldn’t be found.

What were they doing on a cruise together? The long-haired man looked like he’d stepped out of a movie screen. He could have played an ancient conqueror, a great warrior who’d landed incognito into our time. Or perhaps he really was a foreign film star and the young man was his manager. Then again, maybe he was a secret agent or private investigator on a case and the younger guy was his sidekick, likely a computer expert.

What were they doing on a cruise together? The long-haired man looked like he’d stepped out of a movie screen. He could have played an ancient conqueror, a great warrior who’d landed incognito into our time. Or perhaps he really was a foreign film star and the young man was his manager. Then again, maybe he was a secret agent or private investigator on a case and the younger guy was his sidekick, likely a computer expert.

Oh, my. I could create so many stories just from this one person. This had happened to me once before on a cruise. I saw a lady with coiffed white hair and a perfectly made up face who wore elegant Parisian ensembles. She became a countess in my cruise mystery, Killer Knots. How could I use my karate master? Time will tell, but no doubt he’ll show up in one of my books. And his role will be a lot more glamorous than in real life, where he probably was on a pleasure cruise with his partner.

Oh, my. I could create so many stories just from this one person. This had happened to me once before on a cruise. I saw a lady with coiffed white hair and a perfectly made up face who wore elegant Parisian ensembles. She became a countess in my cruise mystery, Killer Knots. How could I use my karate master? Time will tell, but no doubt he’ll show up in one of my books. And his role will be a lot more glamorous than in real life, where he probably was on a pleasure cruise with his partner.

Have you ever met a character so compelling that you had to put him into a book?

With our recent first page critiques we’ve spoken a lot about the importance of a compelling main character – one that draws readers in from the very first page and which transcends (as best you can) the stereotypes common in our genre.

One tool in developing a fully-realized character is to create a questionnaire in which your character gets to answer some key questions about their background, belief and aspirations. An example of such a questionnaire can be found at The Script Lab website, but I thought it may be fun to outline some of the key questions we at TKZ believe are important to know about your character. After all, how can your readers possibly believe in a character that you, as its creator, hardly know yourself.

So here, in no particular order, are some of the key questions I think need to be included in a character questionnaire.

What is it you fear most?

What is it you want the most?

Who are the most influential people in your life, and why?

How do you feel about your mother? Your father? Other members of your family?

What were some of the defining moments in your life?

What tragedies or disappointments have you endured thus far?

What could you not live without? What is your greatest weakness?

What are your strengths?

What do you like the most/least about your appearance?

What is your home like?

How would you describe your appearance?

Do you care about what other people think about you?

Whose opinion do you value?

How do you view authority? Religion? Politics?

Describe your ideal ‘mate’

How have your relationships progressed in the past?

What was your biggest heartbreak?

What gestures do you use?

What speech patterns do you use? Do you swear? Are you self conscious about how you speak?

What is the biggest chip on your shoulder?

So fellow TKZers, do you have any other questions to add to the list? (I’m sure I’ve forgotten something!) Do you use any software to help develop character dossiers or backgrounders? What other techniques do you use to get beneath a character’s skin?

The popularity of the anti-hero (man or woman) continues to be a strong trend in literature and in pop culture. With their moral complexity, they seem more realistic because of their human frailties. They are far from perfect. They tend to question authority and they definitely make their own rules, allowing us all to step into their world and vicariously imagine how empowering that might feel.

Some classic literary anti-heroes that are personal favorites of mine are:

And here is a short list of noteworthy anti-heroes from the small screen:

On the cable show, DEXTER, the strange anti-hero, Dexter Morgan, is a serial killer with a goal. He hunts serial killers and satisfies his blood lust by killing them. He’s got peculiar values and loyalties with a dark sense of humor. And he’s absolutely fascinating to watch.

On the new show HUMAN TARGET, Christopher Chance has a dark history. He’s a do-it-all anti-hero, former assassin turned bodyguard, who is a security expert and a protector for hire. He works with an unusual and diverse team. His business partner, Winston, is a straight and narrow, good guy while his dark friend, Guerrero, is a man who isn’t burdened by ethics or morality. Each of these men has very different feelings about what it takes to get the job done, but they’ve found common ground to work together. And their differences make for a fun character study. (My favorite character is Guerrero and I wish his character had more airtime.)

I’ve put together a list of writing tips that can add depth to your villain or make your anti-hero/heroine more sympathetic, but let me know if you have other tried and true methods. I’d love to hear them.

1.) Cut the reader some slack by clueing them in early. Your Anti-Hero/Heroine has a very good reason for being the way they are.

2.) Make them human. Give them a code to live by and/or loyalties the reader can understand and empathize with.

3.) Make them sympathetic by giving them a pet or a soft spot for a child. Write the darkest character and match them up with something soft and you’ve got a winning combination that a reader may find endearing.

4.) Show the admiration or respect others have for them.

5.) Give your villain and anti-hero similar motivations for doing what they do. Maybe both of them are trying to protect their family, even though they’re on opposing sides.

6.) Give your villain or anti-hero a shot at redemption. What choice would they make?

7.) Understand your villain’s backstory. It’s just as important as your protagonist’s.

8.) Pepper in a backstory that makes your anti-hero vulnerable.

9.) Give them a weakness. Force them to battle with their deepest fears.

10.) Have them see life through personal experiences that we can only imagine but they have lived through. They must be much more vulnerable than they are cynical to deserve the kind of significant other that it takes to open them up to love.

11.) Make them real. To be real, they must have honest emotions.

If you have favorite anti-heroes you’d love to share, I would love to hear from you. And tell us why you like them so much. I’d also like to know if you have any other writer tips to share on creating anti-heroes. Creating them can be a challenge worth taking. Editors sure seem to love them too.