Last week in the comments, Kay DiBianca wrote:

I sure would like to have a master list of the best books for learning the craft of writing.

You asked, you got it.

Now, modesty prevents me from mentioning my own books on the craft. If I was not the humble scribe that I am, I would probably say something like, “These books have proved extremely helpful to fiction writers,” and then I’d put a link to my website for a list of the books.

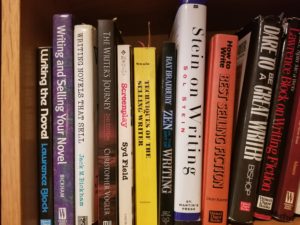

Instead, I will narrow my focus six books which I found most helpful when I was starting out. There’s that old saying, “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” Well, I was ready, and these books appeared. They helped lay a foundation for all my writing since.

Writing and Selling Your Novel by Jack Bickham

Apparently only available in hardback, this is the Writer’s Digest updated version of Bickham’s Writing Novels That Sell (which is the edition I studied). It was his treatment of “scene and sequel” that gave me my first big breakthrough as both a screenwriter and novelist. A light came on in my brain. It was a major AH HA! moment. Bickham’s style is accessible and practical, and a big influence on me when I began teaching. I wanted to give writers what Bickham gave me: nuts and bolts, techniques that work, and not a lot of fluff and war stories.

I found out that Bickham was running the writing program at the University of Oklahoma, where he himself had been mentored by a man named Dwight V. Swain. So I researched Swain, and discovered he’d been a writer of pulp fiction and mass market paperbacks, and written a book a bunch of writers swore by. So naturally I bought it.

Techniques of the Selling Writer by Dwight V. Swain

For those wanting to write commercial fiction (i.e., fiction that sells), this is the golden text. Swain takes the practical view of the pulp writer, the guy who had to produce gripping, ripping stories in order to pay the bills. He lays it all out in a perfect sequence for the new writer, who could go chapter by chapter, building a writing foundation from the ground up. I review my highlighted and sticky-noted copy every year.

Writing the Novel by Lawrence Block

Block was, for years, the fiction columnist for Writer’s Digest magazine. At the same time, he was a working writer himself, having come up through the paperback market and into a series character that has endured, the New York ex-cop Matthew Scudder. Thus, what Block brought to the table was the way a prolific writer actually thinks. The questions I was having as I wrote Block always seemed to anticipate and address. He opens the book with his timeless advice: “If you want to write fiction, the best thing you can do is take two aspirins, lie down in a dark room, and wait for the feeling to pass. If it persists, you probably ought to write a novel.”

Screenplay by Syd Field

This was, I believe, the first “how to” book I bought when I decided I had to try to become a writer. I started out wanting to write screenplays. With writers like William Goldman and Joe Eszterhas getting seven figures for original scripts, I thought, well, maybe this would be a good venture (the only more lucrative form of writing, according to Elmore Leonard, is ransom notes). Field’s book contains his famous “template,” which is a structure model. I studied movies for a year just looking at structure, and finally nailed it. What I added to Field was what is supposed to happen at the first “plot point.” I called it the “Doorway of No Return.” That discovery still excites me.

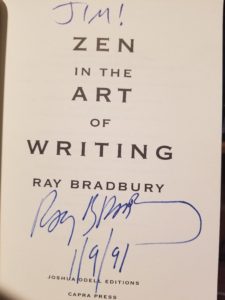

Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury

Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury

This is a right-brain book, and therefore a necessary balance. The secret to elevated writing is finding a way for the rational and playful sides of the writer’s mind to partner up. Bradbury’s book is full of the joy of writing, and it’s infectious. Two of my favorite quotes: “You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.” And: “Every morning I jump out of bed and step on a landmine. The landmine is me. After the explosion I spend the rest of the day putting the pieces together. Now, it’s your turn. Jump!” My signed copy is always within reach.

Stein on Writing by Sol Stein

Sol Stein, 92 years young, is a writer, editor, and publisher (he founded Stein & Day back in 1962). When I started out he had an innovative, interactive computer program called WritePro, which is apparently still available. Much of the advice in the program is in this book, including inside tips on point of view, dialogue, showing and telling, plotting, and suspense.

So there you have it. My list of the books that helped me most when I was starting out. The floor is now open to you, TKZers. What books have you found helpful in your writing journey?