by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Back when I was trying to learn how to write fiction, I joined the Writer’s Digest book club. Each month I’d buy a book or two, devour them, try things out. I have several shelves filled with these books, all highlighted and sticky-noted. Every now and then I like to take one down for a revisit, remembering the lessons I learned.

Back when I was trying to learn how to write fiction, I joined the Writer’s Digest book club. Each month I’d buy a book or two, devour them, try things out. I have several shelves filled with these books, all highlighted and sticky-noted. Every now and then I like to take one down for a revisit, remembering the lessons I learned.

I recently did that with a tome from 1992, The Writer’s Digest Handbook of Novel Writing. It’s a collection of advice from a number of published authors. On the flyleaf I had written five things from the book I especially wanted to remember. Let’s have a look and see if they still apply!

- Be excited about your story

The advice here, from W. C. Stroby, is simple:

Write a story that excites you, challenges you, that keeps you awake at night every time you start to think about it. If you can’t get fired up over it, who will?

“Some books I’ve written come to me because I’ve seen something in the paper that out rages me,” Says Robert Campbell. “A lot of them come out of a philosophical position that is cooked in my mind for many years, until I found the story to tell it. Either way, it has to be something that, in a sense, demands my attention.”

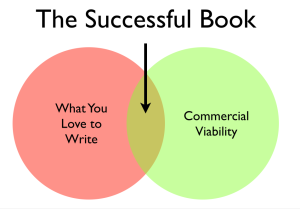

I’ve tried to follow this advice ever since. Whenever I conceive of an idea that might have commercial value, I don’t start writing until I make an emotional connection with the material. I made a Venn diagram for myself which looks like this:

That’s the sweet spot. You can be jazzed as all get out about an idea, but unless you’re going for the obscure genius profile, you need to find a commercial connection. On the other hand, you may think up a high concept for the market, but you then need to work it until the jazz starts up in you, lest you end up writing something “by the numbers.”

Verdict: Still applies.

- Open with dialogue

The great Dwight Swain contributed this chapter. He’s not, of course, advocating always opening with dialogue. But he does cite a pulp editor who told him, “Always open with dialogue, because when two people are talking, they have to be talking about something—something your readers can understand without a lot of explanation.”

Opening with dialogue is a great way to combat throat clearing and info dumping in the first pages. Dialogue automatically makes you write a scene.

The standard criticism you hear (“You can’t open with dialogue because we don’t know enough about who’s talking!”) is the bunk. Readers will wait a long time for info if they’re listening to taut, tension-filled dialogue.

Verdict: Still works.

- One dialogue gem per act

That’s my own term, which I came up with via the same Swain chapter. He advised striving for the “provocative line.”

Hunt for at least occasional new, fresh, original ways for your characters to say whatever it is they have to say. In their proper places, slang, colorful analogies, personification, and the like can prove very effective….Just don’t carry it so far that your readers label it as straining for effect.

Thus I made it a goal to put a colorful line of dialogue (a “gem”) in each act of the book.

Verdict: Why wouldn’t you?

- Withhold information

Swain’s disciple, Jack Bickham, wrote a chapter on scene and sequel. “For dramatic reasons,” he said, “you can withhold information from your readers for a while” making them eager to read on.

An example is when you write in multiple 3d Person. You finish a scene with a disaster for POV 1. How will he get out of this? Instead of showing that next, you cut over to POV 2. Get that POV trapped, and go back to POV 1 or hop over to POV 3! Make ’em wait and turn those pages! This is how I like to do my stand alones, such as Your Son is Alive and Can’t Stop Me.

But what if you write in First Person, as I do in my Mike Romeo series? Here I learned a neat trick from Bickham, what I call the “time jump.” Bickham says he got it from the famous mystery writer Phyllis Whitney, who always wrote in First.

What you do is get to the end of a scene where something major (a setback or shock) happens, or is about to happen. The reader expects the next scene to be about the character’s reaction. But no! You jump ahead in time to another scene, which is about something else entirely. As the reader keeps reading to find out what the heck happened in the last scene, you keep them waiting until a moment when your narrator recounts to another character what the reaction was. They will turn those pages to find out!

With Romeo, since he’s a philosopher who can also beat people up, I’ll sometimes bring him to the brink, when he’s about to be set upon by one or more thugs. Instead of going immediately into the fight, Mike will recall a philosophical point or historical moment that somehow has relevance to what is about to happen. He loves gardening, too, so he may talk about plant life before commencing to blows.

Yes, it’s manipulation, but when you do it well, readers love it.

Just don’t overdo it.

Verdict: Requires skill, but when you pull it off, it’s aces.

- Editors want an author, not just a book

Russell Galen’s chapter is called “How to Chart Your Path to the Bestseller List.” He writes:

Editors are buying you, not just your manuscript. They want to be convinced you’re dedicated to becoming successful; that you have more than one book in you; that your current work is better than your past work, and that your future work will be even better; that you’re looking for a publishing relationship, a long-term home for your work, and not just a deal…Don’t boast that you can write a novel in eleven days—as one writer did to me recently—when editors are looking for evidence that you take pains to make each book as good as it can possibly be.

This was obviously written in the trad-only days, but the advice is just as sound for indies. Readers are looking for new favorite authors, not just books, and if you give them less than stellar work, they won’t stick around waiting for you to measure up. If you want a career out of this, as opposed to a hobby throwing wet spaghetti at the wall, put your work through a grinder.

As Dorothy Bryant puts it later in the book, “Anyone can do a rough draft….The difference between ‘anyone’ and a serious writer is rewriting, rewriting, and grinning over gritted teeth.”

Verdict: If you want to sell widely, pay heed.

Discuss!