by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I love having Brother John Gilstrap back on TKZ. He doesn’t pull punches. He’s the Conor McGregor of writing bloggers. Witness his post last week, Tell the Damn Story. It’s a straight right to the chops.

I love having Brother John Gilstrap back on TKZ. He doesn’t pull punches. He’s the Conor McGregor of writing bloggers. Witness his post last week, Tell the Damn Story. It’s a straight right to the chops.

John and I have gone around on this topic in the past, and I’m inspired by John’s post to do it again today. But rather than get all Floyd Mayweather about it, I’d like to start by looking at where we agree.

There is a lot of good packed into the simple admonition to tell the damn story. To me the gist of this advice is: You are a storyteller, and that is your first and greatest function. So don’t get tied up in “rules” and analysis when you are writing. I even wrote a post on that subject called Avoiding Writing Paralysis Due to Over-Analysis.

John and I agree that when you’re sitting at your typer, with the story in your heart and head yearning to get out, let it out! Get it on the page!

Where John and I part ways is on what to do to make the story better, both before and after the typing.

John says he holds this truth “dear”— “that no one can teach a person to write.” I could pounce on that, but I believe the disagreement may come down to what John means by “to write.” A few lines later John says:

I do believe that instruction and workshopping can hone and develop talent, but it cannot create talent where there is none. Some people are not wired for storytelling.

Ah! Then “to write” for John is tied up in that thing called “talent.” There’s where we could spend more time, talking about what talent really is and how it might be coaxed … or coached.

Further, what John calls “honing and developing” I would simply call “teaching.” So if we parse our terms precisely, I believe John and I would agree that in some measure you can teach a writer things that will make their fiction better.

I also agree that there are some people who are not, as John puts it, “wired” for storytelling. But you know what? In my twenty years of teaching and reading countless manuscripts, I have run across very few who fit this description. The overwhelming majority of writers I’ve taught do have story sense, because how can you avoid it? We grow up reading and watching story after story. We press our reality through the gauze of beginning, middle and end. And most people who come to a workshop do know how to string coherent sentences together. Part of my job as a teacher is to help them stack those sentences in the most effective way.

Which is what the craft is all about.

John further stated in a comment:

A gifted musician is first and foremost gifted. Studying with a master maestro will help him to greatness. For most of us, though, our piano lessons will only help us become really good amateurs. Ditto athletic prowess. Beyond that innate talent, though, there needs to be the drive and desire to work one’s butt off. That work for us writer’s includes not classroom time, but lots and lots of alone time with our imaginary friends.

I liked this up to and excluding the last sentence. We do agree on this basic point: someone with talent can be made better at what they do through lessons. The boy George Gershwin had monster talent, but he needed lesson after lesson for that talent to shine through.

Still, you only get a Gershwin once in a lifetime. But there are countless superb piano players who make good money in bars and restaurants and hotels. They please a lot of people with their music.

It’s the same with writers. There are not many Hemingways or Chandlers, but there are (now) thousands of fiction writers making bank writing entertaining, well-structured, satisfying novels and stories.

Many of them have been my students.

John and I also agree that “working one’s butt off” is a non-negotiable for anyone to make it as a writer. But I am puzzled by his disdain for the classroom. What’s wrong with listening to an experienced writer sharing techniques that make fiction better, stronger, more compelling, and deeper? Why isn’t that something an ambitious writer ought to be anxious to seek out?

At the very least it might save that writer years of frustration and rejection.

Working with a good editor is another way fiction writing is taught. Now, really good fiction editors are rare and always have been. I had the good fortune to work with one of them, Dave Lambert at Zondervan. He was the reason I chose Zondervan over three other publishers back in the day. Dave was famous for his “Dave letters” — multi-page, single-spaced documents of pure insight and instruction. I was a pretty good writer before Dave. He kicked me up several notches. Without his instruction, and my working hard to incorporate that into my pages, I don’t believe I’d be where I am today.

So to me the big disagreement with John comes down to his statement: “The breakthroughs—the true light bulb moments—can only come via self-discovery while pasting butt to chair.”

That’s like saying to a hacker killing gophers on the golf course to just keep hacking, you’ll find your way eventually. Meanwhile, year after year, he continues to stink and give gray hairs to the groundskeepers.

I react this way because my experience is the opposite of John’s axiom. I did write and write, to no avail and no “breakthroughs.” Indeed, I was told several times that “writing can’t be taught.” So I gave it up. For ten long years.

When I finally felt I had to try again, I decided not to listen to the naysayers and started studying the fiction column in Writer’s Digest every month (penned by Lawrence Block, followed by Nancy Kress). I bought writing books and joined the Writer’s Digest Book Club. One of the featured titles, Jack Bickham’s Writing Novels That Sell, gave me the biggest epiphany I’ve ever had in my writing life. It was a huge breakthrough, and led directly to my stuff starting to gain interest, and eventually to sell.

When I wrote, I wrote. But I also valued my study time. And as I tested things on the page, I began to formulate my own theories and techniques and then teach them to others, many of whom have written to thank me for helping them along the fiction journey.

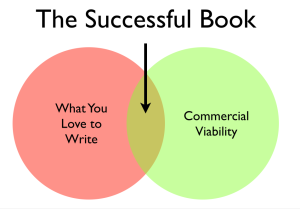

Where would I be if my desire to write had stalled again at the man-made wall with the graffito Writing can’t be taught? In the introduction to Plot & Structure, which keeps selling, I went so far as to call that “The Big Lie.” Because it is.

And now let’s get this deal about “rules” straight. Artists hate that word, because they want to be free! So fine! Don’t use that word!

But do think in terms of fundamentals and guidelines, the tools and techniques that work, that have stood the test of time, and will work for any writer. They are there not only to help you as you try to figure out what to write next, but to help you understand why something you’ve written doesn’t work, and how to fix it.

Perhaps this will ease the conscience of my blog brother: The most important thing a writer can do is produce the words, to write his own stuff, every day if possible. To a quota. That’s always the first and most important thing a writer does. It’s the first advice I always give anyone who asks me what they need to do to become a successful writer.

But I also say this: the writers who have the best chance to make it, to have a career or a good part-time income, will also study their craft with diligence and desire, and without a chip on the shoulder. I’ve seen it happen time after time after time.

Here is my Exhibit A, the highly successful novelist Sarah Pekkanen:

I needed advice before I tried to write a novel. The usual axiom — write what you know — wasn’t helpful. I spend my days driving my older children to school and changing my younger one’s diaper — not exactly best-seller material.

So I turned to experts. Three books gave me invaluable writing advice. One, by a best-selling writer; one, by a top New York agent; and one, by a guy who struggled for years to learn how to write a book and wanted to make it easier for the rest of us.

The books Sarah mentions are Stephen King’s On Writing, Donald Maass’s Writing the Breakout Novel, and my own Plot & Structure. And she explains exactly what she learned from each.

That was back in 2009, just before her debut novel came out. You can check out Sarah’s career trajectory here.

So leave us not speak in extremes. Don’t give us a blanket “writing can’t be taught,” because that is demonstrably false.

On the other side, don’t speak about iron-clad rules. There are critique-group commandos who will take a tip or suggestion and turn it into a law. Like the now infamous Don’t start with the weather. The real guideline should be Don’t start with the weather unless you know how to use it to hook the reader! (For further elucidation on these , see my post on Baloney Advice Writers Should Ignore.)

That’s my case. Fiction writing can be taught .. and learned … and practiced .. and made profitable. I know because I’ve got a huge email file of testimonials to prove it … and I’ve lived it myself.

The boxing ring is now open. Discuss!

***

I would be remiss if I did not mention that the best of my workshops has been put into a complete video course on the craft. It’s called Writing a Novel They Can’t Put Down.

of the fiction pie and is dominated by female authors (along with some guy named Sparks).

of the fiction pie and is dominated by female authors (along with some guy named Sparks).

Back when I was trying to learn how to write fiction, I joined the Writer’s Digest book club. Each month I’d buy a book or two, devour them, try things out. I have several shelves filled with these books, all highlighted and sticky-noted. Every now and then I like to take one down for a revisit, remembering the lessons I learned.

Back when I was trying to learn how to write fiction, I joined the Writer’s Digest book club. Each month I’d buy a book or two, devour them, try things out. I have several shelves filled with these books, all highlighted and sticky-noted. Every now and then I like to take one down for a revisit, remembering the lessons I learned.