by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I write thrillers. That means I major in action. But I do have a lead character who is wont to share an opinion every now and then. That’s one of the things I like about John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee. There are times, briefly (which is the key), when McGee takes a moment to let loose on something. Here’s a bit from The Quick Red Fox:

And so we drove back to the heart of the city. San Francisco is the most depressing city in America. The come-latelys might not think so. They may be enchanted by the steep streets up Nob and Russian and Telegraph, by the sea mystery of the Bridge over to redwood country on a foggy night, by the urban compartmentalization of Chinese, Spanish, Greek, Japanese, by the smartness of the women and the city’s iron clutch on culture. It might look just fine to the new ones.

But there are too many of us who used to love her. She was like a wild classy kook of a gal, one of those rain-walkers, laughing gray eyes, tousle of dark hair –– sea misty, a little and lively lady, who could laugh at you or with you, and at herself when needs be. A sayer of strange and lovely things. A girl to be in love with, with love like a heady magic.

But she had lost it, boy.

Some object to these passages as “stopping the action.” I call it controlling the pace and deepening our bond to the lead character.

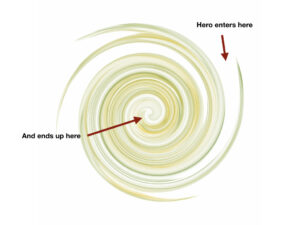

So I wrote a paragraph of my next Mike Romeo thriller expressing an opinion. A bit later I came back to the scene and wrote another paragraph in a similar style. When I edited the first draft I saw that these two bits overloaded and overwhelmed the story.

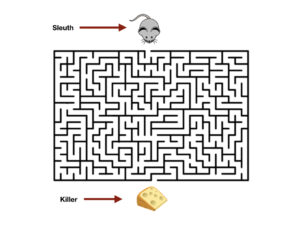

But they were so well written! (I humbly thought). I loved them! Which is the first clue that you have a “darling” on your hands. And we’ve all heard the old saw, “Kill your darlings!”

To me that always sounds like “Destroy your delight” or “Drown your puppies.” Yeesh! I mean, if something is your darling should your first instinct be to kill it? Sounds positively psychopathic.

To me that always sounds like “Destroy your delight” or “Drown your puppies.” Yeesh! I mean, if something is your darling should your first instinct be to kill it? Sounds positively psychopathic.

A darling is at least owed a fair trial!

The phrase has its origin in a lecture on style delivered by the English writer Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch back in 1914. He said:

To begin with, let me plead that you have been told of one or two things which Style is not; which have little or nothing to do with Style, though sometimes vulgarly mistaken for it. Style, for example, is not—can never be—extraneous Ornament … [I]f you here require a practical rule of me, I will presentyou with this: ‘Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it—whole-heartedly—and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.

At least Sir Arthur was honest enough to call it murder! But murder requires malice aforethought, and that is a terrible way to think about a darling.

Darlingcide should be outlawed, not encouraged!

Stephen King strikes the right balance. In his book On Writing King says the whole idea behind “kill your darlings” is to make sure your style is “reasonably reader-friendly.”

Thus, your darlings may be the very thing that distinguishes your voice from the vanilla sameness of so much writing these days, especially in the omnipresent AI epoch which we now inhabit.

Which means sometimes a darling stays, sometimes it goes, and sometimes it gets a skillful edit. In my case, I did remove one of the paragraphs in its entirety. The other I clipped a bit, but it remains largely intact.

It pleases me to write darlings. I do not summarily execute them. I let them sit, I look at them again, I have my wife render an opinion, and then I decide if they must go, stay, or get a loving manicure.

And I know I’ve done good work when I can finally say, “Darling, you look marvelous!”

Comments welcome.

Edmund Burke, the eighteenth century member of Parliament known for his rousing speeches, regarded every word in a sentence as “the feet upon which the sentence walks.” He said that to alter a word—exchange it for a shorter or longer one, or give it a different position—would change the whole course of the sentence.

Edmund Burke, the eighteenth century member of Parliament known for his rousing speeches, regarded every word in a sentence as “the feet upon which the sentence walks.” He said that to alter a word—exchange it for a shorter or longer one, or give it a different position—would change the whole course of the sentence. I love the writing craft. I love it the way

I love the writing craft. I love it the way

George Horace Lorimer was the legendary editor of The Saturday Evening Post from 1899 to 1936. He brought the circulation up from a few thousand to over a million, and made it a place known for quality fiction.

George Horace Lorimer was the legendary editor of The Saturday Evening Post from 1899 to 1936. He brought the circulation up from a few thousand to over a million, and made it a place known for quality fiction. “Once upon a time,” I told my two oldest grandboys, “there were two baby monsters. One was green and one was blue. They lived in a cave with their mom and dad…”

“Once upon a time,” I told my two oldest grandboys, “there were two baby monsters. One was green and one was blue. They lived in a cave with their mom and dad…”