by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I believe it was the writer-director John Huston who once said a great movie has three unforgettable scenes, and no weak ones. Makes sense to me. Maybe that’s the difference between a good book and a great book, a fine read and an unforgettable one. Let’s think about it.

I believe it was the writer-director John Huston who once said a great movie has three unforgettable scenes, and no weak ones. Makes sense to me. Maybe that’s the difference between a good book and a great book, a fine read and an unforgettable one. Let’s think about it.

Huston wrote and directed many great films (let’s not talk about Annie. Why Ray Stark tapped Huston to direct his first and last musical, I’ll never know). One of my favorites is The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) starring Humphrey Bogart, Tim Holt and John’s dad Walter Huston (who took home the Best Supporting Actor Oscar). It’s a stark, noirish drama set in Mexico. The first unforgettable scene (for me) is a brutal fight in a bar, when Bogart and Holt confront the man who owes them money. It’s brilliantly choreographed, and done without musical score.

And then there’s a scene that is with us today, whenever anybody utters the line, “Batches? We don’t need no steenking batches!”

I also love the scene where Walter Huston dances around calling out Bogart and Holt. “You’re dumber than the dumbest jackass! Look at each other, will ya? Did you ever see anything like yourself for bein’ dumb specimens? You’re so dumb, you don’t even see the riches you’re treadin’ on with your own feet. Yeah, don’t expect to find nuggets of molten gold. It’s rich but not that rich. And here ain’t the place to dig. It comes from someplace further up. Up there, up there’s where we’ve got to go. Up there!”

Let’s talk thrillers. Let’s talk The Silence of the Lambs.

There’s the first time Clarice meets Lecter. When I saw the movie I felt a distinct chill throughout my body as Clarice first approaches Lecter’s cell in the bowels of the prison. We watch from her POV and she first lays eyes on him.

He’s just standing there, looking like Anthony Hopkins, in a position that’s hard to describe. It’s almost like he’s at attention, but with the slightest smile that is full of mystery and menace. It just radiated off the screen. And then begins the cat-and-mouse game that is almost ten minutes of pure tension, primarily through dialogue (as in the book as well).

Quieter movies or books need those unforgettable scenes, too. To Kill a Mockingbird has several to choose from. There’s the cross-examination of Mayella Ewell (the movie version is enhanced by the knockout performance by Collin Wilcox as Mayella). At the end there’s the revelation of Boo Radley (brilliantly portrayed by a young Robert Duvall).

And then there’s the scene at the jail where Atticus faces a lynch mob, and the scene takes a most unexpected turn. See for yourselves:

It’s no undiscovered writing tip to say that we ought to strive for unforgettable scenes. Some writers don’t think about it. They just go from scene to scene doing the best they can with them. I prefer to be more intentional.

One of the things I used to do (before Scrivener came on the scene) was take a pack of 3×5 cards to a local coffee establishment and start brainstorming “killer scene” ideas for my upcoming project. I didn’t pre-judge. I just wrote and looked at the cards later. I remember writing cards for my first Ty Buchanan legal thriller, Try Dying. I had this “vision” of Ty getting on a conference table and tap dancing. Wait, what? But it fit in the book as Ty, whose fiance was killed on page one, is in the conference room of a big-time lawyer trying to intimidate him:

I grabbed my notes and stuffed them in my briefcase. With a quick step on the chair I jumped onto the conference table. As Walbert’s eyes opened wider, I did a little three-step tap dance.

“What are you doing?” he howled.

“Gene Kelly,” I said.

“Get off that table!”

“This is what it’s going to be like, Barton. You looking up at me from now on.”

His face changed colors. Cheeks rosy like the dawn. I don’t know why I did it, except that I never liked bullies. On the schoolyard or in a plush conference room.

Gerry Spence, the greatest trial lawyer of his day, was once asked on 60 Minutes what he’d have done if he were a cowboy in the old West, facing a guy with a knife. “I’d leave him bloody on the floor,” Spence said, “which is the way I try cases.”

I jumped off the table and said, “See you in court, Barton. I’m going to leave you bloody on the floor.”

Let your imagination run wild, without judgment. That’s how you get the gold. That’s what Walter Huston would say. He’d point to your head. “Up there’s where you’ve go to go. Up there!”

How about you? What scenes do you remember from books or movies that were unforgettable?

I was happily writing along in my WIP, the next

I was happily writing along in my WIP, the next

Instead of my usual craft post, I’d like to open up a discussion. Here’s the question: How do smartphones impact the way we write thrillers?

Instead of my usual craft post, I’d like to open up a discussion. Here’s the question: How do smartphones impact the way we write thrillers?

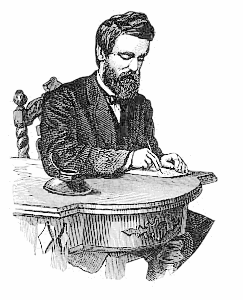

George Horace Lorimer was the legendary editor of The Saturday Evening Post from 1899 to 1936. He brought the circulation up from a few thousand to over a million, and made it a place known for quality fiction.

George Horace Lorimer was the legendary editor of The Saturday Evening Post from 1899 to 1936. He brought the circulation up from a few thousand to over a million, and made it a place known for quality fiction. We’ve often discussed here the different approaches to writing a novel. In dualistic terms, we sometimes use the terms “plotters” and “pantsers.” Or, “outliners” and “intuitive (or discovery) writers.” There are some ’tweeners (“plantsers”), too. Doesn’t matter, as long as the author creates a finished work that’s the best he or she can do.

We’ve often discussed here the different approaches to writing a novel. In dualistic terms, we sometimes use the terms “plotters” and “pantsers.” Or, “outliners” and “intuitive (or discovery) writers.” There are some ’tweeners (“plantsers”), too. Doesn’t matter, as long as the author creates a finished work that’s the best he or she can do. Terry’s

Terry’s