by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Today we have another first page for the TKZ critique machine.

Today we have another first page for the TKZ critique machine.

Last Man Standing

Molly Hammond stared in horror as her fake fingernail strained against the pull tab on her Coke can. Her brain told her to let go, but her hand wouldn’t listen. With a tiny pop, the nail snapped off and made a low sideways arc, landing gracefully in her new boss’s paper plate the man had just placed in front of him on the metal picnic table. As the nail settled between a mound of potato salad and a large helping of barbequed beans, Molly’s fledgling professional life flashed before her light brown eyes.

Oh god!

She stared at the cheap fire engine red plastic glaring back at her and wished with all her heart she could slip quietly beneath the table and down into the bowels of the earth. She was about to reach out to retrieve the cause of her embarrassment when the man slipped his fork beneath the nail along with a small helping of salad. He held it out and motioned in Molly’s direction.

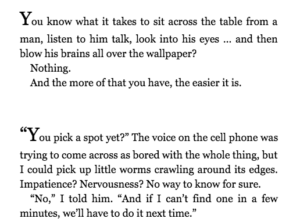

“Well, Ms. Hammond.” He glanced at the fork and tilted his head toward Molly before looking back at the nail, the gesture an offer as well as a question. “I hope this isn’t one of our Your Time products.”

Molly felt her cheeks heat up, certain they’d morphed into the same shade as the nail. She shook her head. “I’m so sorry.” She thought she saw a hint of amusement in his blue eyes but she knew there was nothing funny about making a bad first impression with a no-nonsense businessman like Spencer Steele. He lowered the fork and slid the nail onto his napkin then folded the paper neatly into a small square and tossed it into a trash barrel behind him. Molly kept her eyes on her plate, her right hand in her lap and silently waited for the blazing July morning to finish her off.

JSB: I like this set up. A nervous new employee’s fingernail lands on her boss’s lunch. It’s unique, it’s action, and it is a sudden disturbance in this character’s world. On that last point, this page demonstrates that the opening disturbance does not have to be something “big” like a car chase or a gunfight. It’s enough that it is a matter of emotional importance to the character being revealed to us. A fingernail flying into a superior’s potato salad certainly qualifies.

But in order to take full advantage of this scene, there are a few matters that need to be clarified. We don’t want the reader pausing because the picture isn’t clear.

It’s worth a mention here that there’s a big difference between confusion and mystery. The latter is good. It has the reader thinking I want to keep turning pages to find out what the action is all about. The former is bad. It has the reader thinking I’m not quite sure what’s happening on the page in front of me.

In many cases the confusion is about the setting. That’s the problem here. Where exactly are we? What are the conditions? The picture is a bit out of focus.

When I read metal picnic table I immediately thought of a prison visiting area. That’s probably just my quirk, but in any case we need to know where this table is. We know it’s a meal featuring the employee and her boss. And the trash barrel indicates they are outside somewhere. But where? Are there other people around, or is it just the two of them? Who is “the man” who served the lunch?

The issue can be easily handled with a short paragraph after the first one (which, again, starts with a unique disturbance). Here’s an example:

The annual meet-and-greet picnic for new employees was supposed to be a casual affair. The courtyard of the Your Time Building was abuzz with happy anticipation and easy chatter. Now this!

Now the scene starts to come into focus. Think of it as a gentle turn of the camera lens. The reader can enjoy the rest of the scene now without a lingering question hanging in the background.

Another type of confusion arises when a reader asks something along the lines of Would she really? Here’s what I mean. Let’s go back to the beginning:

Molly Hammond stared in horror as her fake fingernail strained against the pull tab on her Coke can. Her brain told her to let go, but her hand wouldn’t listen.

Cute, but I don’t quite buy it. In this situation—wanting to impress her new boss—the moment her brain fired off that message I think she’d release the tab. Otherwise, I’m skeptical about her ability to be anyone’s employee.

I do like what the author is going for—a slo-mo effect as an embarrassing event unfolds.

We can achieve the same thing by shifting the focus a bit. For example:

With a tiny pop, Molly Hammond’s fake fingernail flew off the pull-tab of her Coke and made a low sideways arc through the air. She watched in horror as it landed gracefully on her new boss’s plate.

Editing Notes

Molly’s fledgling professional life flashed before her light brown eyes.

This is only a minor POV violation, but I’m a believer that these little “speed bumps” take something away from a reader being fully immersed.

So what’s the problem? Molly would not think of her “light brown eyes.” She knows what color her eyes are! As you write, always be firmly inside your viewpoint character’s head, having thoughts she would really have, not thoughts that are signals to the reader.

“Well, Ms. Hammond.” He glanced at the fork and tilted his head toward Molly before looking back at the nail, the gesture an offer as well as a question. “I hope this isn’t one of our Your Time products.”

Another fundamental to embrace is RUE: Resist the urge to explain. This is when the action and dialogue give us all we need to know without you offering up an explanatory line. That just dilutes the effect and gives us another, unnecessary speed bump. Here, you do not need the gesture an offer as well as a question. That’s already obvious from the head tilting and the dialogue.

Molly felt her cheeks heat up, certain they’d morphed into the same shade as the nail. She shook her head. “I’m so sorry.” She thought she saw a hint of amusement in his blue eyes but she knew there was nothing funny about making a bad first impression with a no-nonsense businessman like Spencer Steele.

I found this paragraph a bit clunky. The shaking of the head seems superfluous, and the dialogue is squeezed inside the paragraph. My suggested rewrite:

“I’m so sorry!” Molly felt her cheeks heat up, certain they’d morphed into the same shade as the nail….

[NOTE: Exclamation points should be rare, but I think in this moment one is called for!]

Finally, watch out for the physics of your scene. I like the last paragraph, but there’s some confusion there:

She thought she saw a hint of amusement in his blue eyes…He lowered the fork and slid the nail onto his napkin then folded the paper neatly into a small square and tossed it into a trash barrel behind him. Molly kept her eyes on her plate, her right hand in her lap and silently waited for the blazing July morning to finish her off.

Did you catch it? If Molly is keeping her eyes on her plate, how can she notice his blue eyes and disposal of the nail? It’s an easy fix. After the boss tosses the napkin Molly looked down at her plate, her right hand in her lap, waiting for the blazing July afternoon to finish her off.

[Note: I cut the adverb silently as it’s obvious. And if this is lunch, it would more likely be in the afternoon.]

As you can see, writing friend, there are only small matters here to take care of. Your overall page is a good one. I’m no romance expert, but I can’t help feeling this is an excellent romance setup. Unless Molly decides to murder her boss to save her career…then we’ve got a crime thriller I’d also like to read!

Comments are open.

Scenes are the bricks that build the fiction house. The better the bricks, the better the house. You don’t want bricks that easily crumble or aren’t fitted properly.

Scenes are the bricks that build the fiction house. The better the bricks, the better the house. You don’t want bricks that easily crumble or aren’t fitted properly.