The classic dramatic plot

Recently, I re-read Gone with the Wind. It clocks in at 63 chapters. The first five are what I’d call the opening and the story essentially wraps up in one chapter. So what did Margaret Mitchell fill the 57 chapters in between with? Challenges, obstacles, reversals of fortune for her characters, especially for Scarlett O’Hara. This is the essence of plotting, what keeps the story from bogging down. And it has a definite trajectory. A good plot is like Woody Allen’s shark — if it’s not constantly moving forward — and upward — it dies. (Warning: more shark analogies ahead!)

Let me give you a visual. Which of these plot lines is the best?

The one at top left is a flat line. If you’ve got one of these you’re in big trouble. (Or maybe writing bad literary fiction…sorry, cheap shot). That one below it is almost as bad, a plot that is a yawner until the writer gives you a paddle-jolt climax that comes out of nowhere. The one at top right looks like it would be a nifty thriller — nonstop action! — but it also doesn’t work because the pacing is too frenetic. Think about a roller coaster. Why do people love them? Because the heart-stopping plunges are balanced with quiet moments when we can catch our breath and anticipate the next thrill. And that leaves us with the jagged plot line at the bottom.

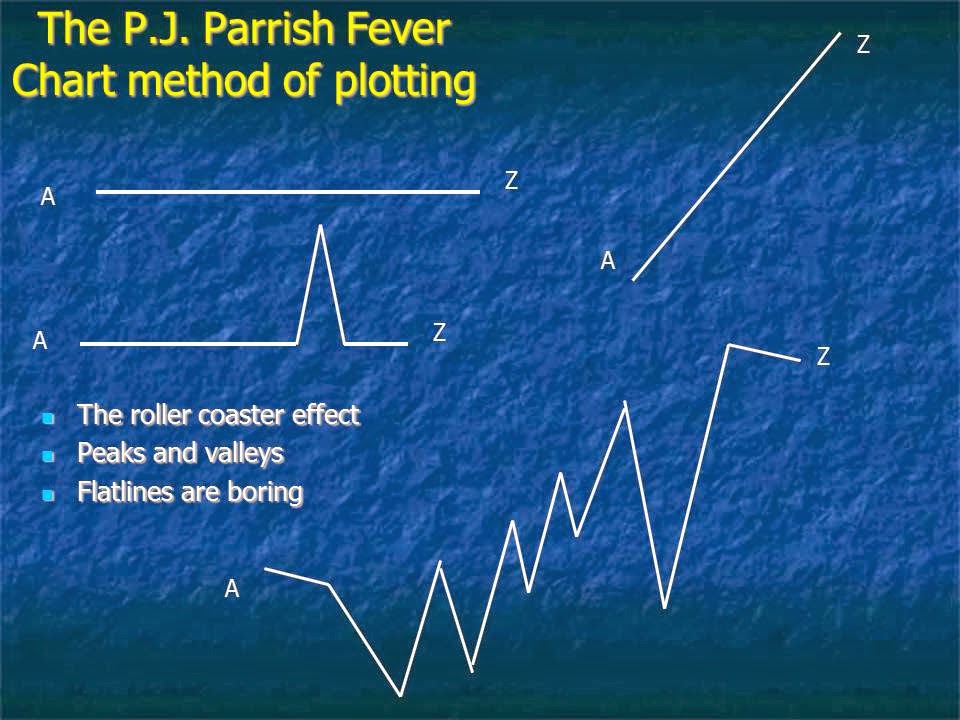

You give me fever!

I call it The Fever Chart Plot because it is graph that charts the protagonist’s fortunes. The trajectory of the story moves forward AND always upward toward the climax but between A and Z it and dips and rises. The beginning A represents an attention-grabbing opening scene. Then there’s a slight dip as we establish characters and setting and define the problem (in crime fiction, usually a murder to be solved). The line dips because as the problem is more clearly defined, it seems increasingly unlikely the hero will ever solve it.

But then the line goes up as the hero begins to cope, fighting his way through a thicket of complications. Sometimes, the plot hits an early high because it looks like the hero has things in hand but then there is a dip — something goes wrong, there is a reversal of fortune. The hero climbs out again only to be confronted with new obstacles along the way. We get another hard climb and more dips. Eventually, the hero achieves a summit of sorts (toward the end) when it looks like he will be triumph BUT…

He is plunged into a final abyss of despair (the last major setback before the climax). This is where your classic tragic plot usually ends. (Hamlet dies). But we’re talking heroic plots here, so just when it looks like all is lost, the hero, through bravery, smarts and fortitude, recovers and soars back, solving the problem once and for all. That little line at the end? That’s just the denouement where little threads are tied up.

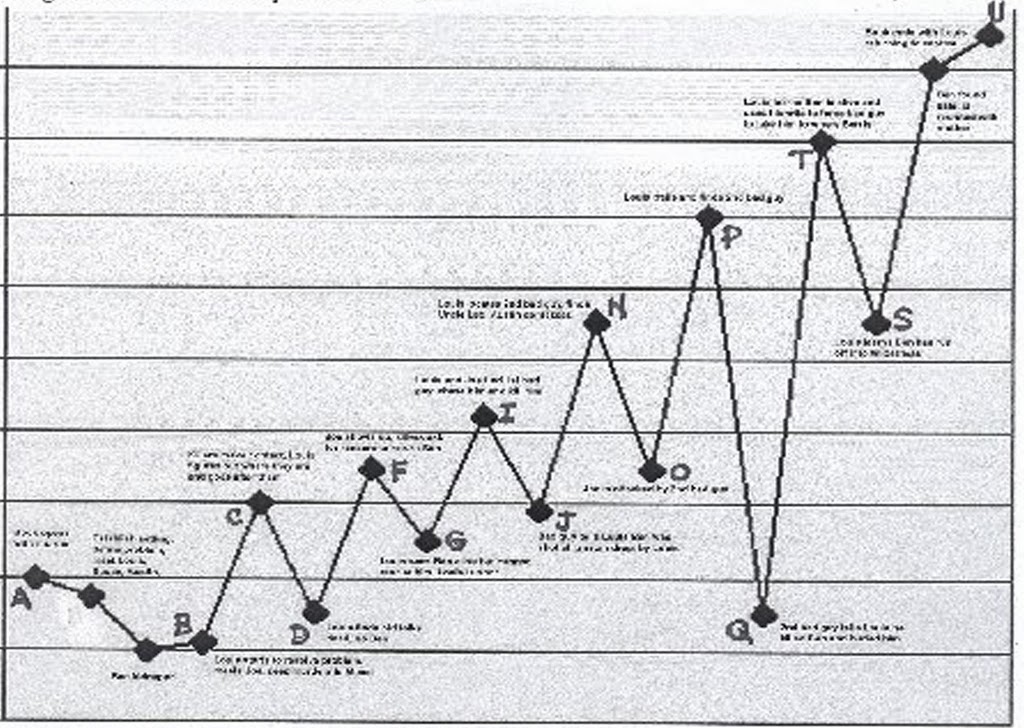

This might seem obvious almost to the point of simple-mindedness, but it is the sturdy scaffolding on which most mysteries and thrillers are built. Your book might have fewer or more dips and rises, depending on the complexity of your story. I once charted out all the plot points of our book A Killing Rain and this is what it looks like:

Tools to dig out of the Muddy Middle

- Setbacks

- Pendulum swings of emotion

- Raising the stakes

- Obstacles

- Rift in the team

- Isolation of the hero

The Amity mayor who’s hellbent on saving the island’s lucrative July Fourth weekend. Brody’s overruled, the beaches stay open and all Brody can do is sit on the beach and sweat. We get a slight rise in the plot graph when Hooper and Brody go out on a night hunt (Hooper is a perfect foil character for Brody, there to give him hope and pull him out of the dips). But then they find that dead guy in the submerged boat and things look increasingly grim. Until we get a major up-thrust for Brody. He gets the money to hire a professional shark hunter — Quint.

Our hero has things under control now, right? Not so fast. Quint is a great character, and he represents one of the most effective devices you can use to beef up your middle — THE RIFT IN THE TEAM. As the three men hunt the shark, the escalating tension between them threatens the quest. You see this device used a lot in cop novels — the errant hard-drinking guy bumping heads with his partner. Think of every partner Dirty Harry ever had. Or watch the sparring between Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey in HBO’s True Detective. Rifts in the team. Brody is pulled down in another dip as he tries to cope with crazy Quint, who at one point even smashes the boat’s radio.

The plot goes into fever pitch after this, with dips and rises as they chase the shark. The STAKES ARE RAISED as their weapons prove futile, and the boat starts to fall apart and the shark even starts to gnaw on it.

We’re entered the final big trough when Hooper decides the only option left is for him to go down in the shark cage. (STAKES ARE RAISED AGAIN). Hooper disappears, presumed dead. And then we begin the final plunge into the abyss for poor Brody. Quint goes out in a blaze of gory…

And there is our hero, alone on a sinking ship, staring into the maw of death. Which brings us to one of the most effective ways to beef up your plot — ISOLATION OF THE HERO. Think of Clarise Starling alone in that creepy basement. We’ve use this device often, putting our hero Louis in abandoned asylum tunnels, on frozen ice bridges on Lake Huron, gator-infested Everglades, and yes, on a sinking boat in the Gulf. It gives your hero that final chance to prove himself — through guts and brains — and triumph over evil. Remember how Brody did it?

Blasted the bad guy to bits. With his final bullet. And he couldn’t even swim. What a guy. What a climax. What a roller coaster ride.

One last note: In the book, Peter Benchley lets the shark just swim away never to be seen again. Which is a really really bad ending. But that is a blog for another day.