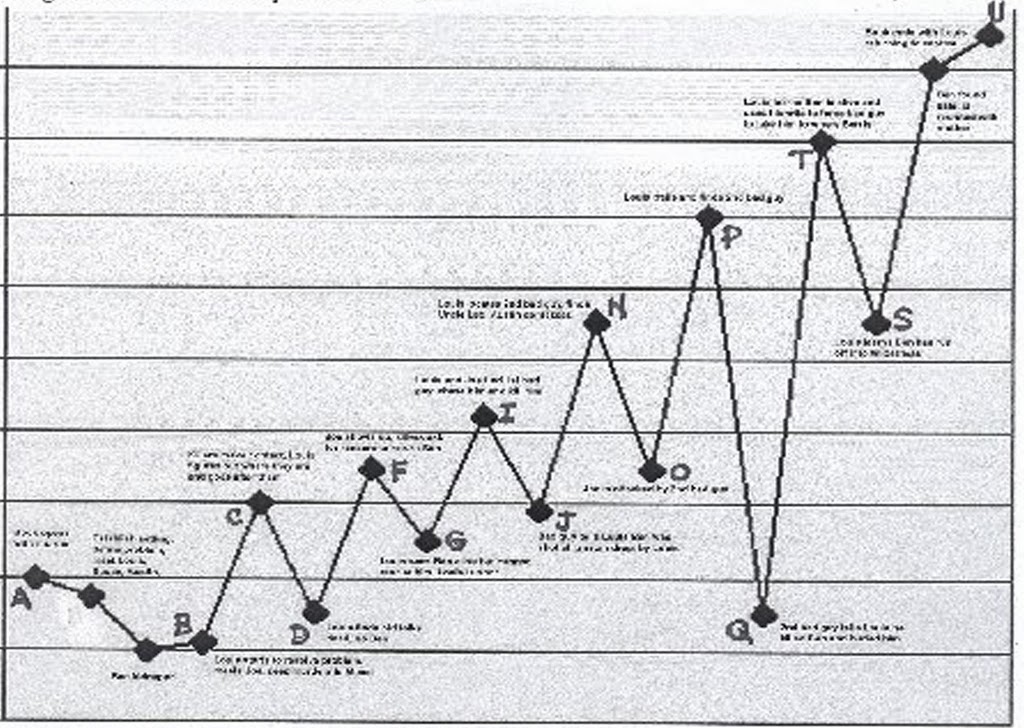

Being a structure guy, I’ve always been fascinated by how story works. When I was first learning the craft, I spent a year studying the 3 Act structure, taking my cues primarily from Syd Field’s classic, Screenplay. In that book, Field talks about plot points, the hinges that lead the plot into Act 2 and Act 3. But I found frustrating a lack of definition of how these plot points worked. What was supposed to be in them? Field knew something happened, he sensed it, but wasn’t quite able to define it.

After watching movie after movie and charting their structures, it came to me. Especially that first plot point, which I began calling “the doorway of no return.” That’s because something has to happen to thrust the lead character into the dangers of Act 2. When you know this in your plot, and put it in the right place, it keeps your novel from dragging and gives it the momentum it needs to carry it to the end. It’s crucially important.

Then, a couple of years ago, I decided to do more in-depth study on what many writing teachers call the “midpoint.” If you do a search about midpoint on the Internet, you’ll find all sorts of ideas about what is supposed to happen here. Some people talk about “raising the stakes.” Others talk about this being the point of commitment. Still others say it’s a change in the direction of the story, or the gathering of new information, or the start of time pressure.

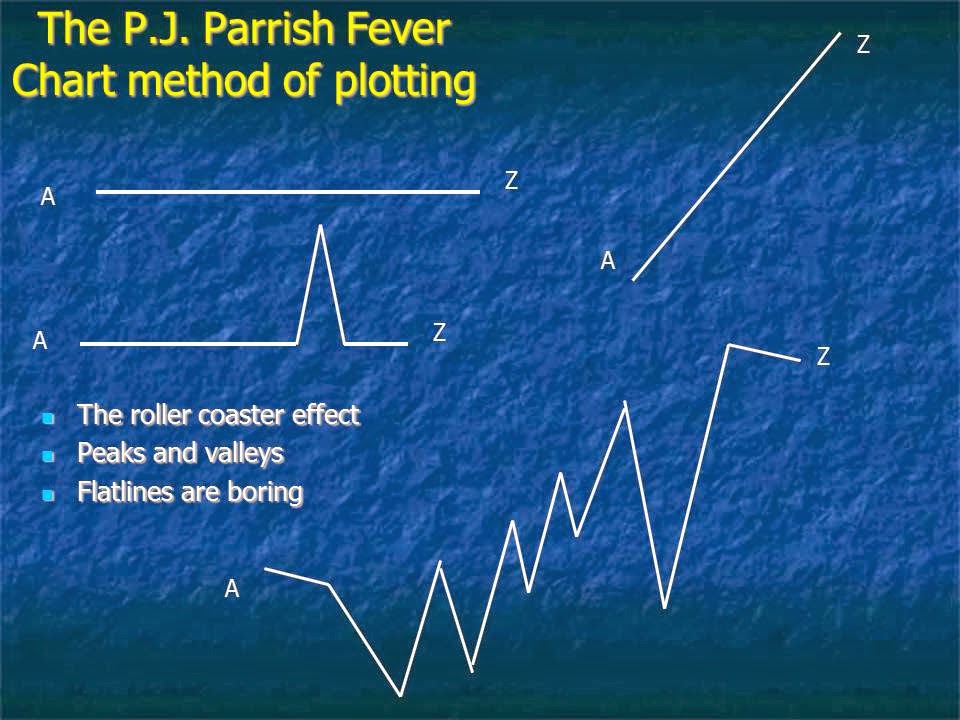

So once again I started watching movies with the midpoint in mind. And what I found blew me away. Even though the writers may not have been conscious of it, they were creating something in the middle of their stories that pulled together the entire narrative. The name I gave it is the “look in the mirror” moment. My workshop slide looks like this:

At this point in the story, the character figuratively looks at himself. He takes stock of where he is in the conflict and, depending on the type of story, has either of two basic thoughts. In a character-driven story, he looks at himself and wonders what kind of person he is. What is he becoming? If he continues the fight of Act 2, how will he be different? What will he have to do to overcome himself? Or how will he have to change in order to battle successfully?

The second type of look is more for plot-driven fiction. It’s where the character looks at himself and considers the odds against him. At this point the forces seem so vast that there is virtually no way to go on and not face certain death. That death can be professional, physical, or psychological.

These two basic thoughts are not mutually exclusive. For example, an action story may be given added heft by incorporating the first kind of reflection into the narrative. This happens in Lethal Weapon when Riggs bares his soul to Murtaugh, admitting that killing people is “the only thing I was ever good at.”

A few more examples may help.

In Casablanca, at the exact midpoint of the film, Ilsa comes to Rick’s saloon after closing. Rick has been getting drunk, remembering with bitterness what happened with him and Ilsa in Paris. Ilsa comes to him to try to explain why she left him in Paris, that she found out her husband Viktor Lazlo was still alive. She pleads with him to understand. But Rick is so bitter he basically calls her a whore. She weeps and leaves. And Rick, full of self disgust, puts his head in his hands. He is thinking, “What have I become?”

The rest of the film will determine whether he stays a selfish drunk, or regains his humanity. That, in fact, is what Casablancais truly about, in both narrative and theme.

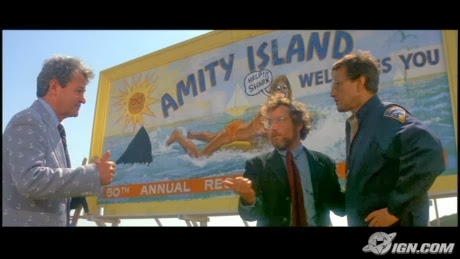

In The Fugitive, an action film, at the very center point of the movie Dr. Kimble is awakened in the basement room he’s renting, by cops swarming all over the place. He thinks they are after him, but it turns out they are actually after the son of the landlord. But the damage is done. Kimble breaks down. He is looking at the odds, thinking there’s no way he can win this fight. There are too many resources arrayed against him.

Then I went looking for the midpoint of Gone With The Wind, the novel. I opened to the middle of the book and started hunting. And there it was. At the end of Chapter 15, Scarlett looks inside herself, realizing that no one else but she can save Tara.

The trampled acres of Tara were all that was left to her, now that Mother and Ashley were gone, now that Gerald was senile from shock . . . security and position had vanished overnight. As from another world she remembered a conversation with her father about the land and wondered how she could have been so young, so ignorant, as not to understand what he meant when he said that the land was the one thing in the world worth fighting for.

Scarlett wonders what kind of person she has to become in order to save Tara. And the decision is made in the last paragraph:

Yes, Tara was worth fighting for, and she accepted simply and without question the fight. No one was going to get Tara away from her. No one was going to send her and her people adrift on the charity of relatives. She would hold Tara, if she had to break the back of every person on it.

And that is the essence of GWTW. It’s the story of a young Southern belle who is forced (via a doorway of no return called The Civil War) to save her family home.

Also, notice how this is different from other definitions of the midpoint you’ll see. Virtually all books on the craft approach it as another “plot” point. Something external happens that changes the course of the story. But what I detect is a character point, something internal, which has the added benefit of bonding audience and character on a deeper level.

In preparing for this post, I grabbed three of my favorite movies and went to their midpoints. Here’s what I found:

In Moontstruck,right smack dab in the middle, is the scene where Loretta goes into the confessional, because she has “slept with the brother of my fiancé.” The priest says, “That’s a pretty big sin.” Loretta says, “I know . . .” And the priest tells her, “Reflect on your life!” He is actually instructing her to look in the mirror!

There’s a perfect mirror moment in It’s a Wonderful Life. It’s the moment where Mr. Potter offers George Bailey a well-paid position with his firm, a job that will mean security for George’s growing family. In return, though, George will have to give up the Building & Loan his father started. Potter offers George a cigar and George asks for time to think it over. He is actually requesting look-in-the-mirror time, and is seriously considering this move. Then he shakes Potter’s hand, and the oily exchange suddenly clarifies what’s at stake for him as a person. “No,” he says, “now wait a minute here. I don’t need twenty-four hours. I don’t have to talk to anybody. I know right now, and the answer’s No!” George had to make a decision as to what kind of man he was going to be. And he chose not to become another Potter.

Finally, in Sunset Boulevard, in the middle of the movie to the minute, Joe Gillis also has to decide what kind of man he is. Norma Desmond, his benefactor and lover, has tried to kill herself because Joe found a girl his own age that he wants to start seeing. When Joe hears about it he rushes back to her mansion with the thought that he’ll finally tell her it’s over, that he’s leaving. But she threatens to do it again. And Joe sits down, literally, next to a mirror. In that moment he makes his fateful decision, the one that drives the rest of the movie.

Could the reason these movies are classics, and others not, be that the writers understood the power of the look in the mirror? Whether instinctive or purposeful, they knew exactly what to do.

Books:

In the middle of The Silence of the Lambs, Clarice is alone in her room, having just heard of Chilton’s betrayal of Lecter, meaning she won’t get any more information from him, meaning the certain death of the kidnapped girl she’s been trying to save. The odds are now firmly against her and the FBI. In the shower, Clarice reflects back on a childhood memory which symbolizes loss for her.

At the midpoint of The Hunger Games, Katniss accepts the fact that she’s going to die. The odds are too great: I know the end is coming. My legs are shaking and my heart is too quick . . . . My fingers stroke the smooth ground, sliding easily across the top. This is an okay place to die, I think.

And, if I may, in the exact middle of my thriller, Try Dying, Ty Buchanan’s home has just been firebombed. His fiancée has been murdered. And he reflects on two kinds of people, those who keep driving toward something, and those who have “given up the fight.”

The question I had, and couldn’t answer, was which kind was I?

Of course, not every film or book will have a “mirror moment” like I’ve described. But the ones that do have a depth about them, a better cohesion and focus, and a satisfying arc. That’s the sort of thing that makes a reader search out more of an author’s work.

Since I incorporated “look in the mirror moment” into my workshops, students have reported it has been incredibly helpful in discovering what their novels are really all about. The nice thing is you can explore this moment at any time in your writing process. You can play with it, tweak it. Whether you are a plotter or pantser, just thinking about what the “look in the mirror” might reveal will help you find the real heart of your novel.