The classic dramatic plot

Recently, I re-read Gone with the Wind. It clocks in at 63 chapters. The first five are what I’d call the opening and the story essentially wraps up in one chapter. So what did Margaret Mitchell fill the 57 chapters in between with? Challenges, obstacles, reversals of fortune for her characters, especially for Scarlett O’Hara. This is the essence of plotting, what keeps the story from bogging down. And it has a definite trajectory. A good plot is like Woody Allen’s shark — if it’s not constantly moving forward — and upward — it dies. (Warning: more shark analogies ahead!)

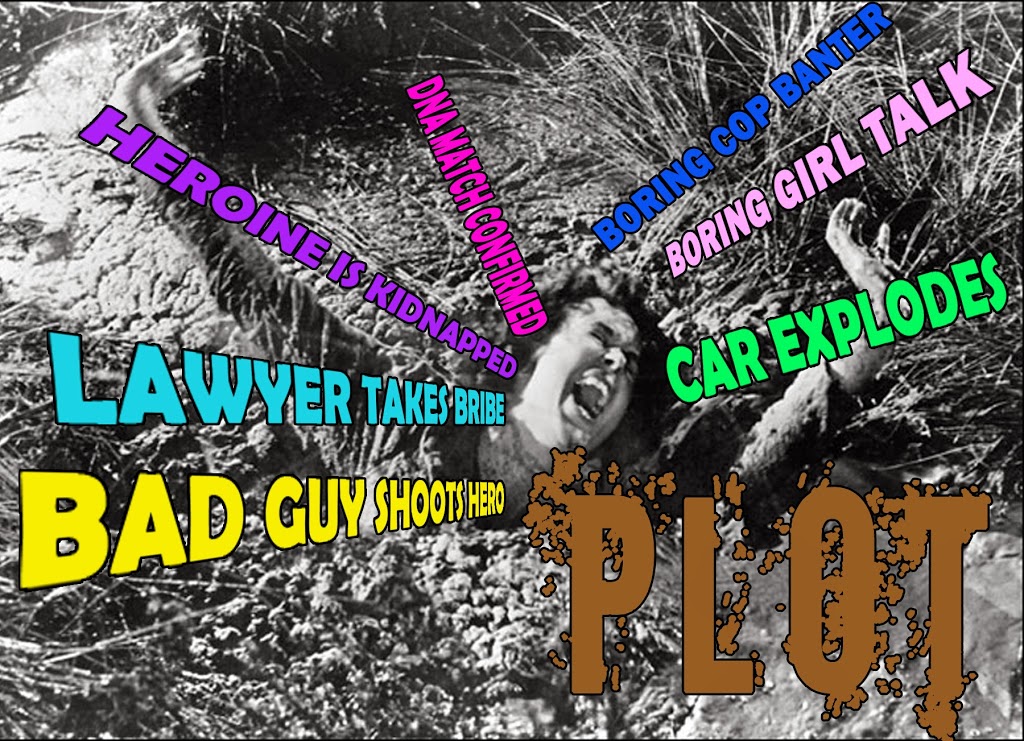

Let me give you a visual. Which of these plot lines is the best?

The one at top left is a flat line. If you’ve got one of these you’re in big trouble. (Or maybe writing bad literary fiction…sorry, cheap shot). That one below it is almost as bad, a plot that is a yawner until the writer gives you a paddle-jolt climax that comes out of nowhere. The one at top right looks like it would be a nifty thriller — nonstop action! — but it also doesn’t work because the pacing is too frenetic. Think about a roller coaster. Why do people love them? Because the heart-stopping plunges are balanced with quiet moments when we can catch our breath and anticipate the next thrill. And that leaves us with the jagged plot line at the bottom.

You give me fever!

I call it The Fever Chart Plot because it is graph that charts the protagonist’s fortunes. The trajectory of the story moves forward AND always upward toward the climax but between A and Z it and dips and rises. The beginning A represents an attention-grabbing opening scene. Then there’s a slight dip as we establish characters and setting and define the problem (in crime fiction, usually a murder to be solved). The line dips because as the problem is more clearly defined, it seems increasingly unlikely the hero will ever solve it.

But then the line goes up as the hero begins to cope, fighting his way through a thicket of complications. Sometimes, the plot hits an early high because it looks like the hero has things in hand but then there is a dip — something goes wrong, there is a reversal of fortune. The hero climbs out again only to be confronted with new obstacles along the way. We get another hard climb and more dips. Eventually, the hero achieves a summit of sorts (toward the end) when it looks like he will be triumph BUT…

He is plunged into a final abyss of despair (the last major setback before the climax). This is where your classic tragic plot usually ends. (Hamlet dies). But we’re talking heroic plots here, so just when it looks like all is lost, the hero, through bravery, smarts and fortitude, recovers and soars back, solving the problem once and for all. That little line at the end? That’s just the denouement where little threads are tied up.

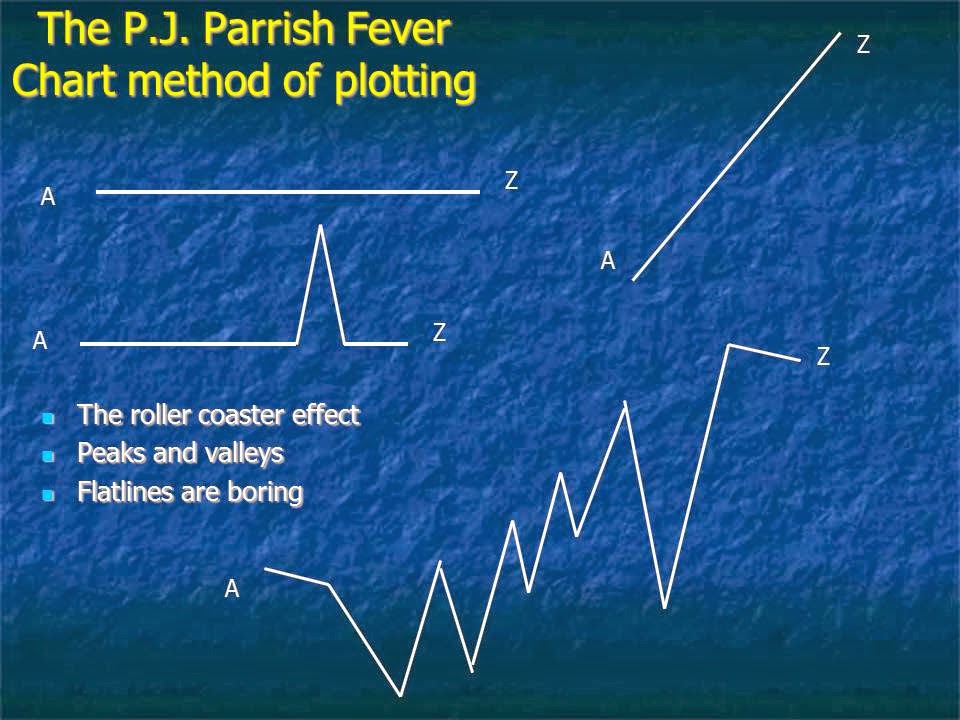

This might seem obvious almost to the point of simple-mindedness, but it is the sturdy scaffolding on which most mysteries and thrillers are built. Your book might have fewer or more dips and rises, depending on the complexity of your story. I once charted out all the plot points of our book A Killing Rain and this is what it looks like:

Tools to dig out of the Muddy Middle

- Setbacks

- Pendulum swings of emotion

- Raising the stakes

- Obstacles

- Rift in the team

- Isolation of the hero

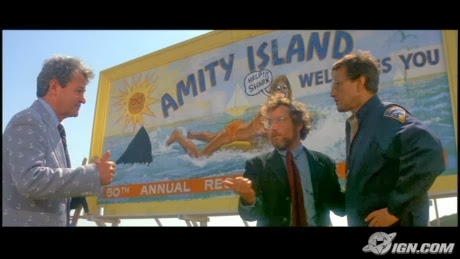

The Amity mayor who’s hellbent on saving the island’s lucrative July Fourth weekend. Brody’s overruled, the beaches stay open and all Brody can do is sit on the beach and sweat. We get a slight rise in the plot graph when Hooper and Brody go out on a night hunt (Hooper is a perfect foil character for Brody, there to give him hope and pull him out of the dips). But then they find that dead guy in the submerged boat and things look increasingly grim. Until we get a major up-thrust for Brody. He gets the money to hire a professional shark hunter — Quint.

Our hero has things under control now, right? Not so fast. Quint is a great character, and he represents one of the most effective devices you can use to beef up your middle — THE RIFT IN THE TEAM. As the three men hunt the shark, the escalating tension between them threatens the quest. You see this device used a lot in cop novels — the errant hard-drinking guy bumping heads with his partner. Think of every partner Dirty Harry ever had. Or watch the sparring between Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey in HBO’s True Detective. Rifts in the team. Brody is pulled down in another dip as he tries to cope with crazy Quint, who at one point even smashes the boat’s radio.

The plot goes into fever pitch after this, with dips and rises as they chase the shark. The STAKES ARE RAISED as their weapons prove futile, and the boat starts to fall apart and the shark even starts to gnaw on it.

We’re entered the final big trough when Hooper decides the only option left is for him to go down in the shark cage. (STAKES ARE RAISED AGAIN). Hooper disappears, presumed dead. And then we begin the final plunge into the abyss for poor Brody. Quint goes out in a blaze of gory…

And there is our hero, alone on a sinking ship, staring into the maw of death. Which brings us to one of the most effective ways to beef up your plot — ISOLATION OF THE HERO. Think of Clarise Starling alone in that creepy basement. We’ve use this device often, putting our hero Louis in abandoned asylum tunnels, on frozen ice bridges on Lake Huron, gator-infested Everglades, and yes, on a sinking boat in the Gulf. It gives your hero that final chance to prove himself — through guts and brains — and triumph over evil. Remember how Brody did it?

Blasted the bad guy to bits. With his final bullet. And he couldn’t even swim. What a guy. What a climax. What a roller coaster ride.

One last note: In the book, Peter Benchley lets the shark just swim away never to be seen again. Which is a really really bad ending. But that is a blog for another day.

Thanks for the great post. We read and learn so much, but when someone puts it all together like this, it makes sense. Guess for this kind of killer plot, the boat was just the right size.

Great post. I think the peaks and valleys graph should have a few very short straight lines in there somewhere for a reader to catch their breath, but I really appreciate the Jaws analysis. I’ve never read the book but I will now.

Another terrific post, on a topic I can’t read enough about. Sharing! Thanks, PJ. (PS…While I realize the graphic on KILLING RAIN is to visually demonstrate plot action, I’d love to be able to read the accompanying text. Because (a) KILLING RAIN is a fave book and (b) my nosy inner writer whines when it sees illegible text.)

Cate: Thanks for the compliment. If you send me an email here via TKZ with your snail mail address I will pop a copy of the original in the mail to you. It is two pages in original so I couldn’t reproduce it here.

Yay! And thanks! I couldn’t figure out how to email the TKZ, so I visited pjparrish.com and sent an email from there. Can’t wait to see it!

Morning crime dogs. Off to dentist so can’t respond in depth but I shall return! See you later.

I truly wish people who are writing about plotting novels would use BOOKS as examples instead of movies.

I understand what you are saying, Elise, but it’s hard to use books because it’s almost impossible to find one that everyone is familiar with. And believe me, showing the plot trajectory of “Jaws” the book would be counterproductive because its structure is just not very good. It’s a heck of a story but as an example of lean linear plotting, it isn’t very effective. Plus I think there is a lot fiction writers can learn from a good screenplay and the elements that go into it.

P.S. I have also used “Silence of the Lambs” (the book) in teaching suspense plotting. Again, the book has subplots that the movie does not but Thomas Harris’s thrillers are top-rate and if you are looking for books to dissect for plot analysis you can’t go wrong with Harris. Well, except maybe “Hannibal Rising.”

I think using movies to talk about story is effective. Movies have to be much more compact than books because they have less time to tell a story. A well done movie script boils a story down to its essentials. Conversely, it’s easy to see where a poorly done movie script falls apart.

Come on, Kris. Letting the shark swim away is no different than letting the lawyer walk out of the courtroom.

Ahem.

Great list for brainstorming trouble. Nicely done.

Ba-da-BUM!

We let a sleazy lawyer go free in one of our books…the readers weren’t happy and let us know it.

Holy Sharknado, Kris! Hooper and Brody’s wife? Ewwww! I didn’t even remember that subplot. But I will remember these tips,esp. Rift in the Team and Isolation of the Hero–new thoughts for me! Thank you!

Benchley and Spielberg battled over the screenplay but in the end, Benchley admitted the screenplay was better. I don’t know why Benchley felt he needed the romantic subplot but it didn’t add a darn thing. Which is a good lesson for all of us. Benchley’s subplot about the class warfare between the islanders and the rich kids who came for the summer was pretty good. But it, too, would have only cluttered up the movie.

They just kept a hint of it, in the dialogue that referred to whether or not one was “an islander.”

Great post. I usually stop reading these kinds of posts because they end up reading as a way to create a formulaic plot. Using JAWS as an example helps a lot. (This may be the greatest example of a movie being better than the book, as you’re absolutely right: there a lot of dreck in the book, and the ending is weak.)

OMG, this is so awesome. I am right at the end of Act III, just one more big scene to wrap up before I get to type “THE END.” Getting through the muck of the middle terrified me as I cast off and put Act I behind me. I think I did a pretty good job. Obviously, my betas will be the judge of that.

But day-um that was hard . . .

Terri,

“Act II” is the hardest part, right? That’s where I am right now and because I am not writing a thriller this time, a structure that I know so well, I am truly at sea. But this is where the book is made.

Actually, I mis-remembered the ending! I went back this morning and pulled my book off the shelf to check the ending and the shark DOES die. It starts swimming toward Brody but then veers away and sinks into the darkness, apparently dying of wounds that Quint inflicts just before he dies. But that ending takes the gun out of the hero’s hand — quite literally. Roy Scheider shooting the oxygen canister and blowing Bruce to bits is far more cathartic.

I also liked that the shark was finally brought down, not by either of the shark hunters, but by the cop using his cop’s weapon, the gun, plus a little ingenuity.

Myth Busters did a show on Jaws. Apparently, they took some liberties with the oxygen tank exploding, but boy did it work.

Ha! Imagine that…Hollywood taking liberties with reality.

Thanks for a great post- and now for my confession…I’ve never actually seen the entire JAWS movie…imagine that!

Excellent post, Kris! What a gold mine of valuable info here for fiction writers! And presented in such a clear fashion, with compelling, spot-on visuals to illustrate your points! Wow!

Thanks Jodie. My posts tend to run on a tad too long but at least I use a lot of pix!

This was really great and I feel like I have something I can use on my story. For those of you who haven’t read Jaws…it’s VERY different from the movie!! I was surprised when I read the book after seeing the movie! I think using the movie was a good idea because it was a movie that kept you guessing what was next. And that is what keeps me reading a book…and not giving up on it!!

So glad it was helpful Chloe.

Middles are so tough for me! I swear by James Scott Bell’s “Plot & Structure,” which helps me through it every time. Thanks for the great rundown. Jaws scared the heck out of me. Sad fact: I didn’t realize it was based on a book :/

You’re not alone, Julie. When I was writing the essay, I went to B&N to get a copy of “Jaws” and the clerk didn’t know there was a book. But there was the paperback…right on the fiction shelf. It’s sort of cool that 40 years later, Benchley’s book is still in stock.

I enjoyed your post PJ. When reading it I kept saying, I know that, I know that – but I find I don’t always do that. We need a reminder of how to make the middle more exciting and you sure provided that.

JAWS is the only book I ever read in one sitting.

I did, too, the first time, Joe. Despite my carping about its faults, I remember enjoying it. Back in 1974, I wasn’t writing fiction and I think that once you write novels, you can lose some enjoyment because you are analyzing how the writer did what he did.

This really helps:) Especially the pics to go with your explanation of the muddy middle ~ getting close to that muddy middle now in my suspense. Thanks for helping me to see it clearer!

Something I saved from Stephen Cannel:

Because Act Two is the hardest act to plot, most people give up on their ideas in Act Two; “This isn’t working.” “This idea sucks.” Most of the time the reason we break down plotting Act Two, is that we tend to “walk” with the hero because we identify with the protagonist. We walk through the story inside his or her head.

Once we get past the complication and are into Act Two, we sometimes get stuck. “What do I do now?” “Where does this protagonist go from here?” The plotting in Act Two often starts to get linear (a writer’s expression meaning the character is following a string, knocking on doors, just getting information). This is the dullest kind of material. We get frustrated and want to quit.

Here’s a great trick: When you get to this place, go around and become the antagonist. You probably haven’t been paying much attention to him or her. Now you get in the antagonist’s head and you’re looking back at the story to date from that point of view.

“Wait a minute… Rockford went to my nightclub and asked my bartender where I lived. Who is this guy Rockford? Did anybody get his address? His license plate? I’m gonna find out where this jabrone lives! Let’s go over to his trailer and search the place.” Under his mattress maybe the heavy finds his gun (in Rockford’s case, it was usually hidden in his Oreo cookie jar). His P.I. license is on the wall. Now the heavy knows he’s being investigated by a P.I. Okay, let’s use his gun to kill our next victim. Rockford gets arrested, charged with murder. End of Act Two.

See how easy it works? The destruction of the hero’s plan. Now he’s going to the gas chamber.

Plot from the heavy’s point-of-view in Act Two; it is an invaluable tip.

Nice formatting

Good point. If your plot and POV structure allows for it, entering the antagonist’s world is very effective.

Thanks for the great tips. Another trick I’ve pulled is to bring a new secondary character on scene. Sometimes this techniques surprises you as well as the reader, and that’s a good thing.

Definitely, Nancy. A well-drawn secondary can really add life to a plot. Sometimes too much! I’ve had secondary guys who’ve become stage hogs.

Holey Moley! Thanks for all that. And in such detail, too.

It’s like a recipe for disaster — in a writer’s good way.

I’m trying to fight through the middle right now. I’m loving the breakdown (Thanks) and I’m even more overjoyed to see that I’m on the right shaky road of dusty doom for my characters. I still have a few evil choices to make, but it looks like if I stay the course just a bit longer, I’ll come out the other side ok.

Must post this excellent post around for others now. Middles have been coming up in conversation a lot lately and this does a great job of making sense of things. 😀

I’m right in the middle of a story. Started it on my blog half heartedly. It has now taken on a life of it’s own with the ideas coming thick and fast. I want to pull it and rewrite the whole story from scratch, it’s too much of a good story to give away for free!