Category Archives: William Faulkner

At the beck and call of…

By John Ramsey Miller

In the early fifties William Faulkner once answered the question as to why he didn’t have a telephone by saying, “I won’t be at the beck and call of any son of a bitch with a nickel.” Calls were cheaper then, and people who couldn’t get a private line often used public phones. I know Bill did have a telephone because there’s one on the kitchen wall at his home, Rowan Oak, in Oxford, Mississippi, with his friends names and numbers penciled on the wall by his and his wife’s hand. Well, he may have said that before his wife decided she wanted everybody with a telephone to be at her beck and call. While there was bourbon in his writing room, there was no telephone.

Recently when I wrote a phone booth into a manuscript and my editor told me there were no such things in New York City any more, just kiosks, which are becoming rarer these days due to cell phones in every pocket––even those pockets without the price of a public phone kiosk call in them. We can communicate with anybody any time, and even pre-tens have cell phones. One crisp winter morning while I was sitting in a stand in the woods in Mississippi deer hunting I got a call from my agent telling me that the first draft of SIDE BY SIDE had been accepted as written. Ten minutes after hanging up, I shot a deer. After I pulled the trigger, I got a second call, this one from a friend on another part of the property asking if that had been my shot he’d heard. Not long ago I was on a panel in New York at Thrillerfest when my son decided to call me to see what I was doing. I covered the phone with my hand to mute it until it fell silent, then I took it out and turned it off. Holy Moto interruption, Batman.

A couple of years back I saw someone using their cell phone to take a picture and I commented to them, “I have a camera that does that.” Today’s cell phones do everything but mix drinks. I’ve been told that mine has games in it, a 5 megapixel camera, a video camera, texting capabilities, a calculator, access to the internet, an audio recording feature, a choice of ring tones, an alarm clock, a clock-clock, and more, but I merely use mine for phone calls. My kids laugh at me because I don’t know what I can accomplish with the tiny privacy invader. And nothing bugs me more than getting a pocket call from someone who sat on the phone and I have to listen to their conversation with someone else, or background noise, while I’m hollering into my phone at them trying to get their attention to complain. Evidently sound enters a pocket easily, but doesn’t travel from one worth a damn.

I am old enough to remember when Dick Tracy wore a wrist watch with a radio in it and how ridiculous and futuristic that seemed at the time. I remember how badly I wanted one, and now for less than $200.00 I can have my choice of several. They make one that also plays music. Check it out: http://www.lightinthebox.com/wholesale-Watch-Style-Cell-Phone_c1298/All-3?gclid=CKGh-uaCu5YCFRKAxgodSSfkmg

The worst thing about writing modern fiction is the problem of instant communication. You can write a technology that doesn’t exist and nobody bats an eye. In one book recently I devised a test (not yet accepted by courts, but in a beta existence) that gave my protagonist DNA results in hours instead of a couple of weeks, and nobody said anything. Because everybody who watches CSI “anywhere” thinks that instant DNA results and access to everybody’s DNA in that city is in a fancy computer database along with fingerprints. If you watch any fictional cop show you see technology at use that (if it existed) would cost cash strapped departments millions of dollars. On TV they do autopsies using holographic images they can view from any angle. In one thriller two men exchanged their actual physical features like they’d exchange two-dollar masks. This is despite the fact that the actors had totally different voices, body types and facial bone structure, and they totally fooled people who’d known them for years. How many cops and criminals are that good an actor.

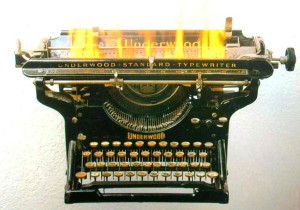

I use modern technology in my plots because––in a world of nanny cams available for a few dollars–– you can’t ignore it, but I have to admit a burning desire to write a book set in the time of scarce phone booths, mobsters who have to be found by their bosses, villains who can’t listen in on the good guys by merely aiming a laser at a window, can’t use GPS to monitor people’s movements from a distance, fire a rifle and kill someone 1500 yards away, make a bomb that can fit into a tube of lipstick, move around the country in private jets, hack into computers, and all the things that make life easier for all of us. I wanted to set a thriller in 1917 a while back––against the backdrop of a famous murder trial––but was informed that period thrillers didn’t sell. Truth is, I’d love to be able to set a thriller during the War Between the States one of these days.

For a long time we have been living in a world catering to instant gratification, and nothing proves that like our need for immediate communication. I have seen people out in the middle of nowhere take out a cell phone and freak out when they can’t get a signal. I have to admit, it’s odd not to be able to get a signal anywhere these days, and it’s getting to where the absence of a signal is very unusual even out here in the middle of nowhere. I only get irritated when I’m doing something important to me and I am interrupted by someone who basically just wants to break up their day by chit-chatting. I don’t mind being called by someone with something to say––especially when I want to hear what they have to say, but sometimes I, like old Bill Faulkner, resent being at the beck and call of…. Well you know.