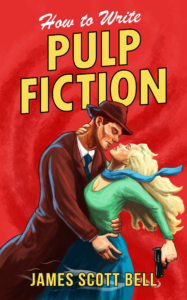

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

In the comments to last Tuesday’s post, Kris asked me about the series of pulp-style stories I’m doing for my Patreon community. It doesn’t take much prompting to get a writer to talk about his work, now does it? So here I go.

My parents were friends with one of the most prolific pulp writers of his day, W. T. Ballard (who also had several pseudonyms). I was too young to realize how cool that was. I wish I’d been aware enough to ask him some intelligent questions about writing! (I’ve blogged about Ballard before.) Fortunately, I was the recipient of many of his paperback books and a collection of his stories for Black Mask about a Hollywood troubleshooter named Bill Lennox. Lennox was like a PI, but did his work for a studio. I thought that was a nice departure from pure detective.

So I decided to create a troubleshooter of my own. The first thing I did was write up a backstory for him:

WILLIAM “WILD BILL” ARMBREWSTER was born in 1899 in Cleveland, Ohio. He grew up on a farm and had a troubled relationship with his father, which led to Armbrewster dropping out of high school and riding the rails as a hobo. He was nabbed by yard bulls in Chicago in 1917 and given a choice: go to jail or join the Marines. He chose the Marines and saw action in France during World War I, most notably at the Battle of Belleau Wood, for which he won the Silver Star. After the war he took up residence in Los Angeles and drove a delivery van for the Broadway Department Store. At night he worked on stories for the pulp magazines, gathering a trunk full of rejection letters.

In 1923 a chance meeting with Dashiell Hammett in a Hollywood haberdashery led to a lifelong friendship between the two. Hammett asked to see one of Armbrewster’s stories, liked it, and personally recommended it to George W. Sutton, editor of Black Mask. The story, for which Armbrewster received $15, was “Murder in the Yard.” After that Armbrewster became a staple of the pulps and was never out print again. Between 1923 and 1940 he averaged a million words a year.

In 1941, after the outbreak of World War II, Armbrewster tried to re-enlist but was turned down due to his age. Instead he went to work for National-Consolidated Pictures, writing short films to inspire the troops. When one of the studio’s young stars was the victim of blackmail, Armbrewster tracked down the perpetrator and dragged him to the Hollywood Police Station. Morton Milder, head of the studio, immediately put Armbrewster on retainer as a troubleshooter.

Known as the man with the red-hot typewriter, Armbrewster wrote many of his stories at a corner table at Musso & Frank Grill in Hollywood. He was granted this favor by the owners, for reasons that remain mysterious to this day (some Armbrewster scholars believe he rescued the daughter of one of the owners from a sexual assault under the 3d Street bridge).

He Lives at the Alto-Nido apartment building, 1851 N. Ivar Avenue, Hollywood.

What is it that I love about pulp writing? Part of it is what Kris called “the streamlined locomotive style.” These stories move. There’s no time for fluff or meandering. Pulp stories were entertainments for people who needed some good old-fashioned escapism from time to time. (That hasn’t change, has it?)

There was also a nobility to the best pulp characters. They had a professional code. Even the most cynical of the lot, Sam Spade, throws over the woman he loves because, “When a man’s partner is killed he’s supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t make any difference what you thought of him. He was your partner and you’re supposed to do something about it.”

I have set my Armbrewster stories in post-war Los Angeles. What a noir town it was then, full of sunlight and shadow, dreamers and drifters, cops and conmen. And, of course, Hollywood.

I’ve now done four Armbrewster stories (which run between 7k-10k words). The fifth is due to be published soon. They aren’t published anywhere but on Patreon, so if you’d like read them you can jump aboard my fiction train for just a couple of berries ($2 in pulp lingo). Go here to find out more.

And thank you, Kris, for asking.

Is there a particular style of writing you warm to? What books or authors do you turn to for pure escapism?