by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

My parents were friends with Todhunter Ballard, a pulp writer from the classic age of Black Mask, Dime Detective and so many others. Later he went on to write paperback Westerns and a number of scripts for TV.

My parents were friends with Todhunter Ballard, a pulp writer from the classic age of Black Mask, Dime Detective and so many others. Later he went on to write paperback Westerns and a number of scripts for TV.

This is called having a career as a professional writer.

Willis Todhunter Ballard was born in Ohio in 1903. By the mid-1920s he’d landed a job with the Brush-Moore chain of Midwestern newspapers. It was not a happy experience. “In eight months I was fired at least eight times,” he told an interviewer. “Besides arguments with the printers, I had them with the old battle-axe who ran the front office. She had been secretary to the Brush boys’ father and considered that she owned the company more than the boys did. It became a routine. She would call me in and fire me, but before I could clear out my desk one or other brother would show up from Europe and rehire me. This went on until one time no one appeared and I stayed fired.”

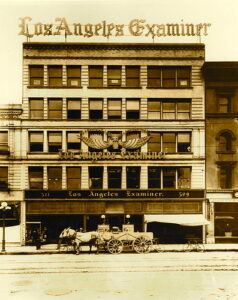

When the stock market crashed in 1929, Ballard tried to find work in the East, to no avail. So he headed for Hollywood where “at least it was warm for sleeping on park benches.” A chance meeting led to some studio writing work, but the gig didn’t last.

One day Ballard went to the movies and saw The Maltese Falcon. Not the later Bogart version, but the original filmed in 1931. He was blown away by the Hammett dialogue and felt it “sounded the way I thought criminals and detectives should talk. It rang true, the way I wanted mine to do.”

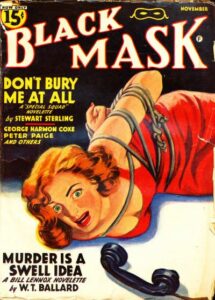

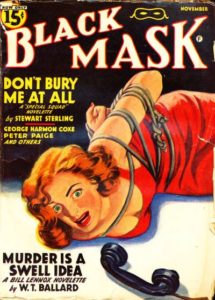

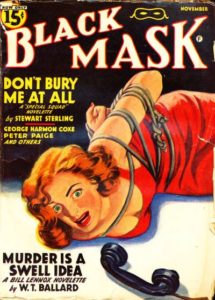

On his way home from the movie, Ballard came up with a series character idea to propose to the famous pulp magazine Black Mask (which had made Hammett famous and would later do the same for Raymond Chandler). Using a friend who worked at Universal as a model, Ballard conceived Bill Lennox, a studio “troubleshooter.” He sat down at a typewriter at midnight and by five in the morning had pounded out ten thousand words. At seven-thirty he put the manuscript in the mail and promptly went to bed.

On his way home from the movie, Ballard came up with a series character idea to propose to the famous pulp magazine Black Mask (which had made Hammett famous and would later do the same for Raymond Chandler). Using a friend who worked at Universal as a model, Ballard conceived Bill Lennox, a studio “troubleshooter.” He sat down at a typewriter at midnight and by five in the morning had pounded out ten thousand words. At seven-thirty he put the manuscript in the mail and promptly went to bed.

A week later he got a check from Black Mask, and his career as a pulp writer took off.

In those days, to make any kind of a living (at a penny a word) you had to be good and you had to be fast. Ballard was both. He treated writing, first and foremost, as a job. It was putting eggs and milk on the table. There was no time to lie back on a sofa and sip sherry, waxing poetic about theories of art.

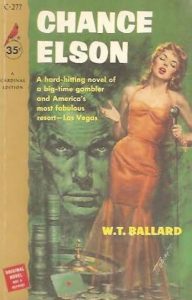

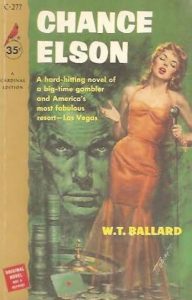

I have a box of Ballard’s books and stories handed down to me by his sister-in-law. In addition to his noir mysteries and paperback originals (as W. T. Ballard), he wrote Westerns (as Todhunter Ballard and under numerous pseudonyms like Jack Slade and Clint Reno).

I have a box of Ballard’s books and stories handed down to me by his sister-in-law. In addition to his noir mysteries and paperback originals (as W. T. Ballard), he wrote Westerns (as Todhunter Ballard and under numerous pseudonyms like Jack Slade and Clint Reno).

In this maturing age of digital self-publishing,I often think of Ballard. Back when things were really taking off, 2009 – 2010 or so, I likened it to a new pulp era, meaning that if you are good, fast, and treat it like a job, you have the chance to make some real dough.

Here’s a bit more of the interview referenced above. Take particular note of the last answer:

Would you tell us something about the lifestyle of a pulp writer living in L.A. during the thirties and forties?

We all worked hard, played hard, lived modestly, drank, but only a few to excess, gambled some when we had extra cash. Most of our friends were other writers. In the Depression when any of us got a check he climbed in his jalopy and made the rounds to see who was in worse straits than he and loaned up to half what he had just received.

What was your yearly average word output for the pulps?

My files are at the University of Oregon library, but a shotgun guess would be about or over a million words per year.

Would you tell us something about your work habits both then and now?

I tried to do about ten pages a day after that first Black Mask flush, sometimes more, sometimes less. I tried to work regularly, something every day even if I later threw it away. These days my wife, Phoebe, does the typing since I’m a lousy typist and in so doing edits the copy. I seldom objected to requests for rewrite but sometimes stood my ground. A late example is a western called Sheriff of Tombstone. Both my agent and my Doubleday editor, Harold Kuebler, held their noses at the first submission and Harold only accepted the altered copy grudgingly. Both let me know in no uncertain terms that they considered it a bad work. It has outsold all my more recent books and is rated second from the top of the list in Western Writers of America’s scoring for the last year.

How about the marketing of pulp fiction? I’ve heard that many of the magazines (such as Frank Armer’s) were closed to most freelancers. Was this a widespread practice?

How did we market pulp fiction? Like selling any other commodity. No magazine I remember was tightly closed to submissions, although a couple of them were written entirely by one or two men for long stretches. It was largely governed by how lazy the editors were, how much they were willing to read.

Frank Armer was no worse than others, but his editor’s were crooked. They were pulling old copy out of the files, slapping a current writer’s name on as author, and drawing checks to the new names, cashing them themselves at the bar on the corner. Bob Bellem and I combined to send them to Sing Sing for five years each. We discovered the ploy after I received a notice from the IRS that I had failed to report $35,000 paid me by Armer Publications. Since I had sold them no copy for that year I checked with Bob. He had sold to them but he was being charged with not reporting twice what he had been paid. We contacted Frank, then blew the whistle.

For nearly fifty years you’ve remained popular to a most precarious profession while other careers have come and gone. To what do you attribute this staying power? Would you share some of your views on the writing business with us?

My views on writing as a business? That it is not much different from any other. You have to keep swinging, rolling with the punches, keep alert and attuned to the changes that take place suddenly or gradually, but always constantly.

JSB: And that, friends, is what a professional writer looks like. Keeping productive, taking a business-like approach. I wrote a whole book on this subject, so I know the fundamentals have not changed since Tod Ballard’s days.

The question for today is, do you look like a professional writer yourself? No matter where you are on the charts, being a pro is always the best course for the future.

People want stories. I would argue people need stories. That’s how the great pulp writers made their living—providing fast-moving tales for readers who longed for escapism, especially during the Great Depression.

People want stories. I would argue people need stories. That’s how the great pulp writers made their living—providing fast-moving tales for readers who longed for escapism, especially during the Great Depression. Armbrewster solves problems for National-Consolidated Pictures. That means getting leading men out of the drunk tank … or a murder rap. It means keeping wolves away from starlets and dancers away from temptation. Once it even means helping Bette Davis out of a jam.

Armbrewster solves problems for National-Consolidated Pictures. That means getting leading men out of the drunk tank … or a murder rap. It means keeping wolves away from starlets and dancers away from temptation. Once it even means helping Bette Davis out of a jam.

I’ve

I’ve