By Debbie Burke

@burke_writer

Photo credit: Josue Isai Ramos Figueroa – unsplash

Jim Bell’s excellent post from Sunday about plotters vs. pantsers serves as an introduction to today’s subject: Is outlining useful for a pantser? Can it be done?

The answer is yes…if you do it in reverse order.

Create the first draft.

Then go back and outline what you’ve written.

In construction, there’s a term called “As Builts.” An architect may start out with an initial blueprint (outline) but the blueprint changes due to circumstances that arise during construction. The finished building is never the same as the original blueprint. Here’s an explanation from Precision Property Management’s site:

“An As-Built drawing should show the building exactly as it currently is, as opposed to a design drawing which shows the intended or proposed layout of the building. This is a critical distinction, because a constructed building almost never corresponds exactly to the original design drawings.”

Like a building, a finished story almost never corresponds to the initial idea. That’s why I don’t outline before writing that initial draft of discovery.

However, once the first draft is finished, I create an outline in the form of as-builts. That’s where the pantser’s errors and oversights show up. And, believe me, there will be plenty.

Oops, I forgot to install reinforcing bars before I poured the slab. Without rebar, the foundation cracks and sags. Gotta jackhammer up the concrete and start over.

Darn, I forgot to include a door that connects the kitchen and the dining room. Better get out the reciprocating saw and cut an opening in that solid wall.

Wow, the shingles on the roof look beautiful…except some of the trusses underneath are missing. The first snowfall causes the whole thing to collapse. Drat.

You get the idea.

Dennis Foley, novelist/screenwriter/educator extraordinaire, introduced me to the concept of “as built” outlines in fiction. He recommends writing in three steps:

- Think it up;

- Write it up;

- Fix it up.

Pantsers feel strangled if we try to adhere to a formal outline during the initial draft. We’d much rather give free rein to our imaginations during Steps 1 and 2.

But, eventually, all that unfettered creativity needs to be organized. Step 3, the “fix it up” stage, is the time to create an “as built” outline.

Outlining in reverse points out structural problems with the plot: events that are out of order, a character who shows up simultaneously in two different places, missing time periods that must be accounted for, lapses in logic, etc. Once those glitches are repaired, the story becomes a coherent sequence of rising complications that ultimately delivers a satisfying climax.

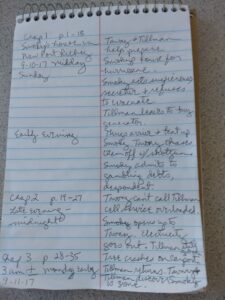

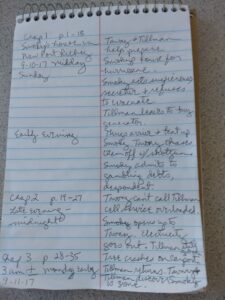

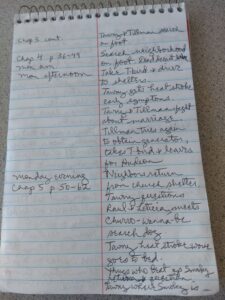

My WIP, Lost in Irma, takes place in Florida during Hurricane Irma in September, 2017, a catastrophe that left 17 million people without electricity. The story covers a two-week period during and after the storm and had to adhere to actual events in the order that they occurred.

The main characters, Tawny Lindholm and Tillman Rosenbaum, are visiting Tillman’s high school coach, Smoky Lido, in New Port Richey when Irma hits. During the height of the storm, Smoky disappears. Tawny and Tillman spend the rest of the book trying to find him. Is he dead or alive? Did he flee because of gambling debts? Was he abducted by thugs he owed money to? Or did he vanish into the storm to commit suicide?

Hurricane-related emergencies overwhelmed law enforcement, leaving Tawny and Tillman on their own to look for Smoky. Power blackouts, gasoline shortages, and unreliable cell service were integral to the plot. They couldn’t make phone calls or search the internet. If they drove, they risked getting stuck in floodwaters or running out of gas.

To pin down significant events on the dates they actually happened, I printed out a blank calendar from September 2017. I filled in the squares with factual information like: what time did Irma hit New Port Richey (late Saturday night, early Sunday morning); what time did the power go out there (around midnight); when did the Anclote River flood (Tuesday)?

To pin down significant events on the dates they actually happened, I printed out a blank calendar from September 2017. I filled in the squares with factual information like: what time did Irma hit New Port Richey (late Saturday night, early Sunday morning); what time did the power go out there (around midnight); when did the Anclote River flood (Tuesday)?

Here’s a link to a handy site that includes sunrise and sunset times for each day, which I also found helpful.

Electricity came back on in fits and starts—one street regained power almost immediately while the next block over stayed dark for days longer. That gave me fictional latitude to turn the power off as long as necessary for plot development.

While researching public shelters, I wondered if there was a roster or record kept of people staying there. Astonishingly, no.

I also learned Red Cross maintains an online “Safe and Well” website where victims of disasters can voluntarily register their names, phone numbers, and leave messages for loved ones. But there is no requirement to register.

I inserted that bit of info into the story, adding that the system can’t be accessed if internet and/or cell service aren’t working or your phone is dead with no way to charge it. That added more complications for Tawny and Tillman, who had to physically go through each shelter, looking for Smoky.

What goes into the as-built outline?

Timelines: The chronology of events is important to nail down correctly which is why I use the calendar technique above.

Scene by scene outline – This traces major characters and plot developments. What day is it? What time is it? Where are they? What action happens?

Scene by scene outline – This traces major characters and plot developments. What day is it? What time is it? Where are they? What action happens?

As you can see from the above illustrations, my outlines are low tech. You may prefer to use Scrivener, Excel, or other spreadsheet programs.

Onstage Characters and Offstage Characters:

Typically, the protagonist appears in most scenes, onstage, and the story is often told from his/her point of view. But if characters are not in a scene—in other words, offstage—they also need to be accounted for, especially in crime fiction.

In mysteries, the murderer’s identity may be withheld from the reader until the very end. But the author still needs to know what that character is up to while s/he is lurking in the shadows. S/he may be trying to elude discovery, throw down false clues, or menace the protagonist. I discussed this topic in a 2017 post.

As a pantser, I often get tripped up because I lose track of a character who’s not onstage at that moment. That’s where the as-built outline catches goofs in the sequence of events.

For instance, the hero can’t find the murder weapon in chapter 4 if the killer doesn’t discard it until chapter 6. Even if you don’t show the killer onstage while he’s tossing the gun off a bridge, you still need to know when that action took place in relation to what the hero is doing. A time line helps point out inconsistencies in the sequential order of events.

Altered Timelines: What if you use flashbacks or jump around in time? Pulp Fiction utilized that technique to memorable dramatic effect. I don’t know how Quentin Tarantino wrote the screenplay but I’m guessing the final version of the film was far different from his initial blueprint.

If you decide to mess around with time conventions, it helps to first write the outline in chronological order. Once that’s done, you can rearrange blocks of time and scenes in any order to best serve your plot line.

Writing About History: If you write historical novels, real events must be accurate. Set up a calendar or time line to cover the duration of the story. This may extend over years or even centuries. Plug in the dates of pivotal events.

For a World War II saga, that might translate to a time line like:

1939 – Nazis invade Poland

1940 – Dunkirk evacuation

1941 – Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

1942 – Battle of Midway, etc.

Other genres: Even if you write sci-fi or fantasy where the story world is entirely made up, that world must still conform to its own time system that is consistent and logical within its parameters. Suppose in your sci-fi, time travels backwards rather than forward. Events happen in reverse order of what we’re used to. The story might start with the death of a character, then goes backwards year by year, to their birth. Within that logic system, you would see the effect before the cause, the consequence before the action that triggers it.

Time travel stories especially require a clear time line. When you zigzag back and forth through history, it’s easy to get confused. If the author is lost, the reader will also be lost and likely give up on your book.

Jordan Dane just published a gripping time-travel thriller, The Curse She Wore. Maybe she’ll chime in on her techniques to handle multiple time lines.

As-built outlining may seem bass-akward but, for this pantser, it works.

~~~

TKZers: What are your favorite techniques to organize a plot?

~~~

Debbie Burke first used reverse-outlining in her award-winning thriller, Instrument of the Devil. On sale for only $.99 at this link.

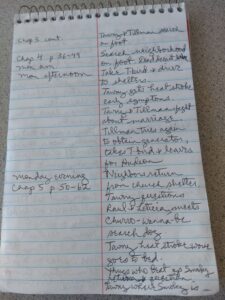

I’ve written before about the pulp writer W. T. Ballard. He was a friend of my parents, and I only wish I’d been aware enough to arrange a sit-down with him to talk writing. Alas, he died in 1980 while I was still trying to become the next Brando.

I’ve written before about the pulp writer W. T. Ballard. He was a friend of my parents, and I only wish I’d been aware enough to arrange a sit-down with him to talk writing. Alas, he died in 1980 while I was still trying to become the next Brando.