by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I left a comment on the first-page Kris critiqued last Tuesday. I suggested the author eschew backstory and exposition, except what was put into confrontational (as opposed to expositional) dialogue. Kris asked if I might expand on that.

Patricia Medina and Bruce Bennett in “The Case of the Lucky Loser.”

First, let’s define terms. Exposition is information, stuff a reader needs to know in order to fully understand what’s going on in a scene and, indeed, the whole book. The key word here is needs. A common mistake, especially in opening pages, is too much exposition in the narrative. That was the problem with the manuscript Kris critiqued. It had a couple of long paragraphs of pure information (an “info dump”). The author thought them necessary for readers to understand what was going on. Not so. Readers will wait a long time for full exposition if they’re caught up in a tense scene. My standard advice is Act first, explain later.

Yet sometimes a bit of backstory or exposition is called for, and the best way to deliver that info is through dialogue. But it has to be confrontational and sound like it’s really two characters saying what they would say in that situation.

Let me demonstrate with an example. In many TV dramas of the 50s and 60s, the set-up was sometimes larded with dialogue that sounded forced, that was there just to give the audience information. Here’s a bit from the old Perry Mason series starring Raymond Burr. In “The Case of the Lucky Loser” we open with a man and woman in a train compartment:

HARRIET: I still wish I were going to Mexico with you instead of staying here in Los Angeles.

LAWRENCE: This trip’s going to be too dangerous, Harriet. It’s some of the most rugged terrain in the Sierra Madre mountains. It’s no place for a woman, especially my wife. It’s almost no place for an amateur archaeologist, either. Thanks for coming with me as far as Cole Grove Station.

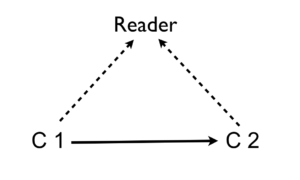

Yeesh! What’s wrong with that is called “the false triangle.” The dialogue should sound like two characters talking to each other, like this:

But when the author tries to “cleverly” send the reader information, the transaction looks like this:

The solution is simple: Make the dialogue confrontational. That doesn’t mean it has to be a big argument, though that always works. Just insert enough opposition so there’s some tension. The Perry Mason example could go like this:

“Let me come with you,” Harriet said.

“That part of Mexico’s too dangerous,” Lawrence said.

“It’s dangerous in L.A., too, unless you haven’t noticed.”

Lawrence laughed and stroked her hair. “The Sierra Madres are no place for—”

“If you say a woman again I swear I’ll file for divorce.”

“Honey—”

“You’re an insurance salesman, not an archaeologist! The only rocks you should be looking at are in your head.”

“Now, now.” Lawrence looked out the window. “We’re coming into Cole Grove Station.”

“Don’t make me get off,” Harriet said.

“See you in two weeks,” Lawrence said.

Find any dialogue in your manuscript where you’ve slipped into the “false triangle.” Transform that conversation into confrontation. Then look for places where you’ve dropped a paragraph or more of raw exposition. Cut out any information that can wait until later, and see if you can put what’s left into a conversation between two characters.

Say, why don’t we try it now? Here’s a bit of expositional dialogue. Show us in the comments what you can do to make it confrontational:

There was a knock at the door. Molly opened it.

“Well hello, Frank,” Molly said. “What brings my favorite accountant all the way out here to Mockingbird Lane?”

“Hi, Molly,” Frank said. “I wonder if we might have a chat about your tax return for last year, when you got that $35,000 advance on your first novel, When the Wind Whips, from Simon & Schuster. Who says an author has to be in her twenties or thirties to start a career, eh? May I come in?”

“Sure,” Molly said, opening the door for him.

“You could have called,” Molly said. “I would have been happy to drive my Tesla to your office where my friend, Linda, is your receptionist.”

“That’s all right,” Frank said. “I need to take off a few pounds as you can see, so the walk did me good.”

Have fun!