by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I left a comment on the first-page Kris critiqued last Tuesday. I suggested the author eschew backstory and exposition, except what was put into confrontational (as opposed to expositional) dialogue. Kris asked if I might expand on that.

Patricia Medina and Bruce Bennett in “The Case of the Lucky Loser.”

First, let’s define terms. Exposition is information, stuff a reader needs to know in order to fully understand what’s going on in a scene and, indeed, the whole book. The key word here is needs. A common mistake, especially in opening pages, is too much exposition in the narrative. That was the problem with the manuscript Kris critiqued. It had a couple of long paragraphs of pure information (an “info dump”). The author thought them necessary for readers to understand what was going on. Not so. Readers will wait a long time for full exposition if they’re caught up in a tense scene. My standard advice is Act first, explain later.

Yet sometimes a bit of backstory or exposition is called for, and the best way to deliver that info is through dialogue. But it has to be confrontational and sound like it’s really two characters saying what they would say in that situation.

Let me demonstrate with an example. In many TV dramas of the 50s and 60s, the set-up was sometimes larded with dialogue that sounded forced, that was there just to give the audience information. Here’s a bit from the old Perry Mason series starring Raymond Burr. In “The Case of the Lucky Loser” we open with a man and woman in a train compartment:

HARRIET: I still wish I were going to Mexico with you instead of staying here in Los Angeles.

LAWRENCE: This trip’s going to be too dangerous, Harriet. It’s some of the most rugged terrain in the Sierra Madre mountains. It’s no place for a woman, especially my wife. It’s almost no place for an amateur archaeologist, either. Thanks for coming with me as far as Cole Grove Station.

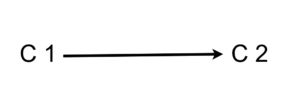

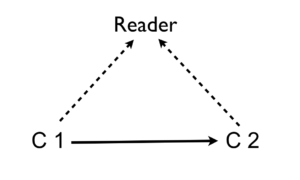

Yeesh! What’s wrong with that is called “the false triangle.” The dialogue should sound like two characters talking to each other, like this:

But when the author tries to “cleverly” send the reader information, the transaction looks like this:

The solution is simple: Make the dialogue confrontational. That doesn’t mean it has to be a big argument, though that always works. Just insert enough opposition so there’s some tension. The Perry Mason example could go like this:

“Let me come with you,” Harriet said.

“That part of Mexico’s too dangerous,” Lawrence said.

“It’s dangerous in L.A., too, unless you haven’t noticed.”

Lawrence laughed and stroked her hair. “The Sierra Madres are no place for—”

“If you say a woman again I swear I’ll file for divorce.”

“Honey—”

“You’re an insurance salesman, not an archaeologist! The only rocks you should be looking at are in your head.”

“Now, now.” Lawrence looked out the window. “We’re coming into Cole Grove Station.”

“Don’t make me get off,” Harriet said.

“See you in two weeks,” Lawrence said.

Find any dialogue in your manuscript where you’ve slipped into the “false triangle.” Transform that conversation into confrontation. Then look for places where you’ve dropped a paragraph or more of raw exposition. Cut out any information that can wait until later, and see if you can put what’s left into a conversation between two characters.

Say, why don’t we try it now? Here’s a bit of expositional dialogue. Show us in the comments what you can do to make it confrontational:

There was a knock at the door. Molly opened it.

“Well hello, Frank,” Molly said. “What brings my favorite accountant all the way out here to Mockingbird Lane?”

“Hi, Molly,” Frank said. “I wonder if we might have a chat about your tax return for last year, when you got that $35,000 advance on your first novel, When the Wind Whips, from Simon & Schuster. Who says an author has to be in her twenties or thirties to start a career, eh? May I come in?”

“Sure,” Molly said, opening the door for him.

“You could have called,” Molly said. “I would have been happy to drive my Tesla to your office where my friend, Linda, is your receptionist.”

“That’s all right,” Frank said. “I need to take off a few pounds as you can see, so the walk did me good.”

Have fun!

Very helpful tip. And very timely. I’m going through and making revision notes on a project this week so it will help greatly to keep this in mind while identifying and fixing those long spots of exposition. Because it’s one thing to know you need to identify those long paragraphs of exposition & convert them to dialogue where possible, but it’s another thing to know how to dialogue in a more appealing way to the reader.

As an introvert who does a lot of pondering, the downside is it’s too easy to slip into exposition mode in my writing. And it’s so critical to think about sharing only what’s needed to move the story along because as an author, I’m wrestling with the other side of that coin which is the author’s worry that we haven’t explained things in a clear enough manner to avoid confusing the reader (say for example the multitude of characters that populate a book).

“…but it’s another thing to know how to dialogue in a more appealing way to the reader.”

Just remember, readers love arguments.

Molly swung open the door. “What do you want, Frank?”

“Did you think I wasn’t going to notice that you left out the twenty-five-grand advance from Simon and Schuster?”

Molly rolled her lips. “That might be all I ever make on my novel. What’s the big deal?”

“The big deal, as you say, is the IRS wants their money. Advances are taxable income.”

“Not if you hide it well enough.”

“Do you want me to lose my accountant license? Is that it?”

“Next time call. I didn’t buy a Telsa to have it sit in my driveway.” 😀

Love it, Sue!

👊👊👊

Love this!

*curtsy* 😉

I second the motion for Sue’s confrontational dialogue. I don’t think I could say it better.

Thanks, Jim. This was a great explanation of confrontational vs. expositional dialogue. Very helpful.

👍

Great post on “As you know, Bob”-info dump dialogue, Jim, with excellent examples and diagrams which were very helpful.

To me, effective, engaging dialogue is like a taut tennis match, with back-handed returns, dives to reclaim the point, sudden lunges, and surprises, for the character and thus the reader. Sue’s example beautifully illustrated that.

“As you know, Bob”

Danny Simon called this the “Here we are in sunny Spain” opening. 😁

Dale, the tennis match visual is a terrific analogy. .

I am so stealing this for my seminar at Midwest Writers Workshop this week. With full credit to you, Jim (of course).

Far out! Thanks, pal.

Molly jerked the door open. “Frank! Don’t have time for you right-”

“Make time, sweetheart, or you can kiss your book advance goodbye.”

“Why Frank, whatever are you talking about-”

“Don’t even. I’m your accountant, not your greasy mechanic.”

“But-”

“Now sit down and let’s talk.” Frank pointed to a chair. “Maybe we can come to some equitable agreement. You know, the kind where we both come out winners? The kind where I help you hide that $35,000 from the IRS goon squad, and then go buy a fancy Tesla like you did. Hmm?”

Molly sat.

***

Great fun on a Sunday morning, Jim! 🙂

Love the interruptions, Deb. That’s always a good way to add tension to dialogue (just remember to use the em dash).

The only thing I would change in your example is “Why Frank….” She already said his name once. Other than that, we are on our way to a thriller!

Yeah, the em dash. How do you do that here at TKZ? I use it all the time in Word, but I’ve tried here and it doesn’t work. Is it an HTML code?

Thanks!

https://www.toptal.com/designers/htmlarrows/punctuation/em-dash/

A bit cumbersome. For our purposes here, I think two dashes–works fine.

Learned me again! See below—

🙂

My word processor autocorrects two equals signs (==) into one em dash (—), which I can copy here. Or I can copy it from the Ubuntu character map. Or it can be copied from the post, as in, “The Sierra Madres are no place for—” Or use two hyphens, as JSB suggests.

And good suggestion about using Frank’s name twice. 🙂

But Jim—

👍😁

Jim, that Perry Mason title sounded familiar. I dug through a few stacks of old books and, voila, found a 1957 hardback of The Case of the Lucky Loser published by Walter J. Black.

Here’s the opening page:

Della Street, Perry Mason’s confidential secretary, picked up the telephone and said, “Hello.”

The well-modulated youthful voice of a woman asked, “How much does Mr. Mason charge for a day in court?”

Della Street’s voice reflected cautious appraisal of the situation. “That would depend very much on the type of case, what he was supposed to do and–”

“He won’t be supposed to do anything except listen.”

“You mean you wouldn’t want him to take part in the trial?”

“No. Just listen to what goes on in the courtroom and draw conclusions.”

“Who is this talking, please?”

“Would you like the name that will appear on your books?”

“Certainly.”

“Cash.”

“What?”

“Cash.”

“I think you’d better talk to Mr. Mason,” Della Street said.

Much better opening! Of course. It’s ESG.

This is great (of course). My dilemma arises when my cop is by himself and trying to put together pieces of the case he’s working on. Whenever possible, I try to get someone else into the scene, but when they’re working together, they’re being more cooperative than confrontational. I toss in some banter, some sarcasm, but bottom line is they’ve got the same agenda, and finding the solution is done by working together.

Of course, the whole idea of the “cop buddy” movies is that two with the same agenda on a case can have opposing agendas in life, e.g., Lethal Weapon.

Love this! I’m afraid my travel-weary mind wouldn’t do justice to writing a scene tonight, but I understand the concept and can’t wait to try it out in one of my two WIPs. Thanks.

This sounds like fun. As I’ve never been one to shy away from public humiliation, let me try.

***

Molly gave a soft sigh before pulling open the front door. ‘What do you want?”

“Nice to see you, too,” Frank said. “You didn’t mention that you’d moved to Mockingbird Lane.”

“Must have slipped my mind. What do you want?”

“When I did your taxes last year, you never mentioned a thirty-five thousand dollar advance from your publisher.”

“Must have slipped my mind. Besides, don’t I pay you to hide stuff like that?”

“I don’t take part in money laundering.”

“Well then, can’t you just give it a thorough rinse? Is that why you’re sweating?”

“It was a shorter walk to your previous address.” His eyes were looking over my shoulder at the living room. “It’s hot out here. Didn’t your mother teach you manners?”

I stepped to the side, sweeping my arm in my best Vanna White motion. “Please, Frank. Won’t you come inside. Mi casa es mi casa.”

He took a seat on the couch while I grabbed him a bottled water from the fridge. “Regardless,” he yelled to be heard in the kitchen. “We still have to pay taxes.”

“You should have called, I said. “I would have picked you up at your office. What’s there not to like about a ride in my new Tesla?”

“Spontaneous combustion comes to mind.”