by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

During Abraham Lincoln’s law-practice days, he had occasion to share a stagecoach with his soon-to-be adversary, Stephen A. Douglas, and a man named Owen Lovejoy. They were on their way to the courthouse at Bloomington, Illinois.

During Abraham Lincoln’s law-practice days, he had occasion to share a stagecoach with his soon-to-be adversary, Stephen A. Douglas, and a man named Owen Lovejoy. They were on their way to the courthouse at Bloomington, Illinois.

Douglas, known as “The Little Giant,” was about five feet tall with a long body and short legs. Lovejoy, on the other hand, had a short body and long legs. Lincoln, of course, was 6’4”. It must have been crowded in that coach.

At one point, Douglas tossed some shade at Lovejoy, remarking on his “pot belly” and long legs. Lovejoy came back with a barb about Douglas’s vertically-challenged sticks.

Then Lovejoy looked at the future president and asked, “Abe, just how long do you think a man’s legs should be in proportion to his body?”

Lincoln replied, “I have not given the matter much consideration, but on first blush, I should judge they ought to be long enough to reach from his body to the ground.”

And how long should a story be? Long enough to reach the end, and no longer. (Please note, I have not run this theory by George R. R. Martin.)

Which is why I love the novella form. In a brisk 20k-50k, you can grab a reader and deliver a wallop. Did you know that The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain is only about 35k words? Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea has a similar count.

Stephen King has done some of his best work in novellas (e.g., The Body and Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption)

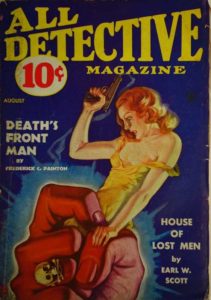

The novella really matured during the golden age of the pulp magazines. In the classic years of the pulps, roughly 1920 – 1955, America was awash in inexpensive commercial fiction of all types. These were printed on cheap wood-pulp paper, bound between wonderfully lurid covers. You could buy one of these magazines for a dime or 15¢, and inside you’d have a plethora of short stories and novellas and perhaps even an entire novel (or an episode from a novel in serialization).

The novella really matured during the golden age of the pulp magazines. In the classic years of the pulps, roughly 1920 – 1955, America was awash in inexpensive commercial fiction of all types. These were printed on cheap wood-pulp paper, bound between wonderfully lurid covers. You could buy one of these magazines for a dime or 15¢, and inside you’d have a plethora of short stories and novellas and perhaps even an entire novel (or an episode from a novel in serialization).

A productive pulpster who could deliver the goods could make a living, even at a penny a word.

The novella largely disappeared after the death of the pulps. It was a difficult sell for book publishers who had to price them to make a profit, while bookstore browsers thought they might not be getting enough story for the price.

That didn’t mean the occasional novella didn’t break out (***cough***The Bridges of Madison County***cough***). But by the 2000s there were few being published simply because production costs exceeded revenue.

Now, because of the digital universe, those costs have disappeared, which has brought a revival of novella-length fiction.

Like the one I’ve just published.

Here’s how Framed came about. A couple of years ago I was playing the first-line-game. That’s a creativity exercise where you just come up with great opening lines and see if any of them spark a story idea. I’ve got a whole file full of ’em, some of which have led to published work.

Here’s how Framed came about. A couple of years ago I was playing the first-line-game. That’s a creativity exercise where you just come up with great opening lines and see if any of them spark a story idea. I’ve got a whole file full of ’em, some of which have led to published work.

This particular morning I found myself writing It’s not every day you bleed to death.

I had no idea who my character was or how he or she got into the implied predicament.

So I started to play with it. How could this have happened? Was it a suicide or attempted murder? Did my character have a near-death experience? Could he be narrating from the beyond?

I kept asking myself what if questions and writing things down, and eventually came up with an explanation that I liked. And from there I proceeded to develop the story.

I set it aside for awhile as I worked on other projects, then late last year came back to it and finished it. And you know how I knew it was done?

Because its legs had reached the ground. The ending felt just right.

So now, in the spirit of the pulps, I am launching the ebook for just 99¢ on Kindle. I want you to have it. I believe there is a huge market for brisk, suspenseful fiction, just like there was in the 1930s and 40s.

Do you agree?