by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

He was 44 years old, an alcoholic, and had just been fired from his job because of his drinking. The Depression was in full tilt. Married, with savings running low, he had to find a way to make a living.

He was 44 years old, an alcoholic, and had just been fired from his job because of his drinking. The Depression was in full tilt. Married, with savings running low, he had to find a way to make a living.

So he decided to become a writer. Ack!

Because of his background in business (he’d been an oil company executive for thirteen years), Raymond Chandler approached his new vocation systematically.

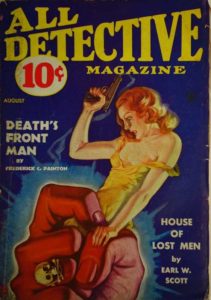

He started with an adult education course called Short Story Writing. He read pulp magazines, especially the famous Black Mask, with an analytical eye on what the writers did in their stories. He would make a detailed synopsis of a story by, say, Erle Stanley Gardner, then rewrite it in his own way, compare it with the original, then rewrite it again. That’s not a bad method for learning the craft.

What he didn’t see a lot of was style, a certain “magic” in the prose. (This reminds me of John D. MacDonald’s goal of “unobtrusive poetry.”)

Thus he began to type on strips of paper half the normal size. This forced him to put down choice words, and if he felt they didn’t work he could toss out the 15 lines or so and start again.

He kept notebooks, jotting down potential titles, story ideas, characters, and his observations of people, especially the clothes they wore and the slang they used.

His writing routine was based on time, not output (he was admittedly slow on the production side). He sat at his typewriter for four hours in the morning, until lunch. If the words didn’t come, he didn’t force the matter. If a writer doesn’t feel like writing, Chandler said, “he shouldn’t try.” (I have to disagree with the master here. But who am I to cavil? In 1939 he published The Big Sleep, got a bunch of Hollywood money, and became famous over time.)

He wrote to please himself and the reader. He once said in a letter, “I have never had any great respect for the ability of editors, publishers, play and picture producers to guess what the public will like. The record is all against them. I have always tried to put myself in the shoes of the ultimate consumer, the reader, and ignore the middleman.”

Of the two writers he was most associated with, he had this to say: “Hammett is all right. I give him everything. There were a lot of things he could not do, but what he did he did superbly. But James Cain—faugh! Everything he touches smells like a billygoat.”

And get this, from a 1947 letter: “I wrote you once in a mood of rough sarcasm that the techniques of fiction had become so highly standardized that one of these days a machine would write novels.”

Ha! (He also said technique alone could never have the “emotional quality” needed for memorable fiction. Looking at you, AI.)

For Chandler, the priority order of fiction factors seems to have been: style, characters, dialogue, scenes, plot. He was not a plotter. Far from it. In a 1951 letter to his agent, Carl Brandt, he wrote: “I am having a hard time finishing the book. Have enough paper written to make it complete, but must do all over again. I just didn’t know where I was going and when I got there I saw that I had come to the wrong place. That’s the hell of being the kind of writer who cannot plan anything, but has to make it up as he goes along and then try to make sense out of it. If you gave me the best plot in the world all worked out I could not write it. It would be dead for me.”

There are definitely plot holes in Chandler, the most (in)famous being who killed the chauffeur in The Big Sleep? When Warner Bros. was doing the movie, they sent a wire to Chandler asking who the murderer was. Chandler replied, “I don’t know.”

But here’s the thing. We remember Chandler, and place him atop the pantheon of hardboiled writers, because of what he emphaszied—his style. I mean, look at some of these gems:

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Ana’s that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. – “Red Wind”

Bunker Hill is old town, lost town, shabby town, crook town. Once, very long ago, it was the choice residential district of the city, and there are still standing a few of the jigsaw Gothic mansions with wide porches and walls covered with round-end shingles and full corner bay windows with spindle turrets. They are all rooming houses now, their parquetry floors are scratched and worn through the once glossy finish, and the wide sweeping staircases are dark with time and cheap varnish laid on over generations of dirt. In the tall rooms haggard landladies bicker with shifty tenants. On the wide cool front porches, reaching their cracked shoes into the sun, and staring at nothing, sit the old men with faces like lost battles. – The High Window

I lit a cigarette. It tasted like a plumber’s handkerchief. – Farewell, My Lovely

There was a sad fellow over on a bar stool talking to the bartender, who was polishing a glass and listening with that plastic smile people wear when they are trying not to scream. – The Long Goodbye

She smelled the way the Taj Mahal looks by moonlight. – The Little Sister

It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window. – Farewell, My Lovely

“I’m an occasional drinker, the kind of guy who goes out for a beer and wakes up in Singapore with a full beard.” – “Spanish Blood”

The girl gave him a look which ought to have stuck at least four inches out of his back. – The Long Goodbye

So, my writer friends, what do you think? Is style the secret ingredient over plot and character? We usually talk about the importance of character within a plot, or vice versa. But Chandler worked hard for that “magic” in his prose and, well, his books are still selling!

There’s a great Far Side cartoon (among so many great ones from the genius Gary Larson). It shows the back of a man seated at a desk. He has a pencil in his fingers, but his hands are grabbing his head in obvious frustration. In front of him are a series of discarded pages with MOBY DICK, Chapter 1 at the top. They say:

There’s a great Far Side cartoon (among so many great ones from the genius Gary Larson). It shows the back of a man seated at a desk. He has a pencil in his fingers, but his hands are grabbing his head in obvious frustration. In front of him are a series of discarded pages with MOBY DICK, Chapter 1 at the top. They say: