“You ever killed anything?” Roy asked. (Dean Koontz, Voice of the Night)

The car was just sitting there, its hazard lights blinking like beacons in the darkness. (P.J. Parrish, Paint it Black)

I was talking to a woman about flowers when John the Baptist blew up. (James Scott Bell, Romeo’s Rules)

An opening line like the ones above grabs the reader and pulls them into the story. The hook at the end of the chapter propels the reader forward, making them turn to the page to find out what happens next. Yet another hook is the book description itself, which gets the reader hooked into opening the novel to read that first line.

In today’s Words of Wisdom, Kathleen Pickering discusses favorite opening hook techniques, Nancy Cohen tackles end of chapter hooks and Jodie Renner looks at how to hook the reader with a book description. The full posts are date-linked from their respective excerpts. Afterwards, I’ll have a few questions as fuel for our discussion.

Hooks–so many types! Of the various suggested techniques, I’ve listed my five favorite hooks below.

- Three-Pronged Hook. This is a wonderful approach using three sentences to pull the reader deeper into the story.

Here are three, expertly crafted Three-Pronged Hooks:

“I sleep with the dead. I don’t remember the first time I did it and try not to think about why. It’s just something I do.” (In the Arms of Stone Angels, by Jordan Dane)

Or:

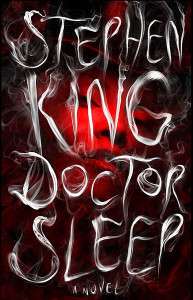

“Two Whom It May Concern: My name is Wilfred Leland James and this is my confession. In June of 1922 I murdered my wife, Arlette Christina Winters James, and hid her body by tupping it down an old well. My son, Henry Freeman James aided me in this crime, although at 14 he was not responsible; I cozened him into it, playing upon his fears and beating down his quite normal objections over a period of 2 months.” (Full Dark, No Stars by Stephen King)

Or:

“The boy stood naked in the middle of the road. Sam Hall’s headlights caught him there, frozen in position, like a deer. He was covered in something slick and it dripped down his flesh.” (The Evil Inside, by Heather Graham)

Makes you want to read more, yes? You’ll also see that expertly composed hooks manage to combine techniques to create a masterful atmosphere. With hooks created by the guest authors I’ve featured here today, if readers were fish, they’d be jumping into the boat.

- Startle Hooks.These hooks capture audiences quickly because the readers can’t quite believe what they’ve just read (like those hooks above). Folks will keep reading to discover what is really going on. Another example, and shameless plug, is in Mythological Sam-The Call, where Sam Wilson starts the first chapter with a surreal visual:

“I steer around the bend and my breath catches in my throat. A hideous, mythological hydra suspends across the bay, clawing each shore with twin, snarling heads straining towards the sky.” (Mythological Sam-The Call by Kathleen Pickering.

Couldn’t help but include myself here, especially in such good company, but I hope you’ll agree that no normal dude driving along the road is going to see a snarling, mythological beast where a bridge is supposed to be. I’d like to think the startle factor will keep the audience reading to learn what’s really happening.

- Describe a personality and elicit emotion. See how a master handles this one:

“Myron lay sprawled next to a knee-knockingly gorgeous brunette clad only in a Class-B-felony bikini, a tropical drink sans umbrella in one hand, the aqua clear Caribbean water lapping at his feet, the sand a dazzling white powder, the sky a pure blue that could only be God’s blank canvas, the sun as soothing and rich as a Swedish masseur with a snifter of cognac, and he was intensely miserable.” (The Final Detail, by Harlan Coben).

Superbly done. (Applauding from my chair!) This hook flashes Myron as a law enforcer of high caliber who knows danger, attracts sexy women, lives life like a hedonist and is bored out of his gourd, eliciting both envy and concern from the reader over a intriguing personality. All done in one sentence. Amazing.

- Establish a Setting. Mr. Coben also combines setting into the above hook, so I will cite the same quote. While establishing a setting is a gentler hook, when professionally cast as Coben has done, the results reel readers in hook, line and sinker. (I just know you were waiting for me to use that cliché!)

- Introduce the Main Character. This hook is most effective when working with character driven plots, especially if the author is establishing a series with a particular character. Here, F. Paul Wilson’s character, Repairman Jack, has developed a cult-like following by portraying a darkly dangerous Jack with a quirky yet endearing, under-the-radar life style.

“Jack looked around the front room of his apartment and figured he was either going to have to move to a bigger place, or stop buying stuff. He had nowhere to put his new Daddy Warbucks lamp.” (Conspiracies – Repairman Jack Series, by F. Paul Wilson)

Kathleen Pickering—September 27, 2011

Creating a hook at the end of a chapter encourages readers to turn the page to find out what happens next in your story. What works well are unexpected revelations, wherein an important plot point is offered or a secret exposed; cliffhanger situations in which your character is in physical danger; or a decision your character makes that affects story momentum. Also useful are promises of a sexual tryst, arrival of an important secondary character, or a puzzling observation that leaves your reader wondering what it means.

It’s important to stay in viewpoint because otherwise you’ll lose immediacy, and this will throw your reader out of the story. For example, your heroine is shown placing a perfume atomizer into her purse while thinking to herself: “Before the day was done, I’d wish it had been a can of pepper spray instead.”

This character is looking back from future events rather than experiencing the present. As a reader, you’ve lost the sense of timing that holds you to her viewpoint. You’re supposed to see what she sees and hear what she hears, so how can you see what hasn’t yet come to pass?

Foreshadowing is desirable because it heightens tension, but it can be done using more subtle techniques while staying within the character’s point of view.

Stick to the present, and end your chapter with a hook that stays in character.

Here are some examples from Permed to Death, my first mystery novel. These hooks are meant to be page turners:

“This was her chance to finally bury the mistake she’d made years ago. Gritting her teeth, she pulled onto the main road and headed east.” (Important Decision)

“There’s something you should know. He had every reason to want my mother dead.” (Revelation)

“Her heart pounding against her ribs, she grabbed her purse and dashed out of her town house. Time was of the essence. If she was right, Bertha was destined to have company in her grave.” (Character in Jeopardy)

“She allowed oblivion to sweep her into its comforting depths.” (Physical Danger)

Personal decisions that have risky consequences can also be effective. For example, your heroine decides to visit her boyfriend’s aunt against his wishes. She risks losing his affection but believes what she’s doing is right. Suspense heightens as the reader turns the page to see if the hero misinterprets her actions. Or have the hero in a thriller make a dangerous choice, wherein he puts someone he cares about in jeopardy no matter what he decides. Or his decision is an ethical one with no good coming from either choice. What are the consequences? End of chapter. Readers must keep on track to find out what happens next.

To summarize, here’s a quick list of chapter endings that will spur your reader to keep the night light burning:

-

Decision

2. Danger

3. Revelation

4. Another character’s unexpected arrival

5. Emotional turning point

6. Puzzle

7. Sex

Nancy Cohen—April 9, 2014

BACK COVER COPY

Your back cover copy or book description is the biggest deciding factor for readers picking up your book for the first time. Not only does it have to be enticing and polished, but it has to strike at the heart of your actual story, hint at the genre and tone, and incite curiosity among the readers, to compel them to open the book and read the first page (which, as you know, is also critically important).

Your back cover copy or book description needs to:

– Grab readers’ attention – in a good way

– Incite curiosity about this book

– Tell us roughly what the story is about

– Give an indication of the genre and tone of the book

– Introduce us to the main character and his goal

– Tell us the protagonist’s main problem or dilemma

– Leave us wanting to find out more

James Scott Bell (Yes, TKZ’s beloved Sunday columnist and writing guru) gives us a great template for writing strong, compelling back cover copy in his excellent book, Plot & Structure.

Jim’s outline is a perfect jumping-off point for creating your own book description.

Paragraph 1: Your main character’s name and her current situation:

__________________ is a ________________ who ___________________________________.

Write one or two more sentences, describing something of the character’s background and current world.

Paragraph 2: Start with Suddenly or But when. Fill in the major turning point, the event that threatens the character, disrupts his world and forces him to take action. Add two or three more sentences about what happens next.

“But his world is turned upside down when…”

Paragraph 3: Start with Now and make it an action sentence, for example, “Now (name) must struggle with….”

Or use a question or two starting with Will: Will (name) be able to….? Or will she….? And will these events….?

Then add a final sentence that is pure marketing, like “(Title) is a riveting…. novel about …. that will …you…till the … twist at the end.

Now polish it up, making sure every word counts and you’ve used the best possible word for each situation. Aim for about 250-500 words in total.

There are of course many other ways to grab your readers in your book description, but be sure to use the main character’s name and hint at the threat that has upset his world and the obstacles he needs to overcome to win, survive or defeat evil, and right wrongs. And leave the readers with a question, to pique their curiosity and propel them into the story.

Then, if there’s space, you could squeeze in a great blurb or two, or a short author bio.

Jodie Renner—July 13, 2021

***

- Do you have a favorite type of opening hook to grab the reader? How do you come up with one?

- Which sort of end of chapter hook (AKA “mini-cliffhangers”) have you used? How much do you focus on them when revising your novel?

- What do you think of Jodie’s elements of an effective book description? Anything to add?

- Do you have any books or other resources you’ve found helpful in coming up with hooks?

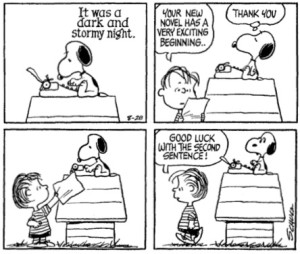

There’s a great Far Side cartoon (among so many great ones from the genius Gary Larson). It shows the back of a man seated at a desk. He has a pencil in his fingers, but his hands are grabbing his head in obvious frustration. In front of him are a series of discarded pages with MOBY DICK, Chapter 1 at the top. They say:

There’s a great Far Side cartoon (among so many great ones from the genius Gary Larson). It shows the back of a man seated at a desk. He has a pencil in his fingers, but his hands are grabbing his head in obvious frustration. In front of him are a series of discarded pages with MOBY DICK, Chapter 1 at the top. They say: