“Remember that writing is translation, and the opus to be translated is yourself.” – E.B. White

By PJ Parrish

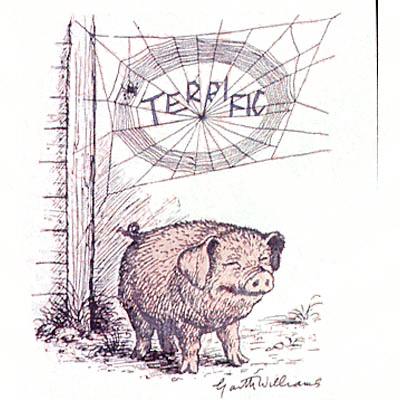

Writers are often asked what their favorite book is. Or which one most influenced them as a writer. The first question has always been easy for me — my favorite book is E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. But it has only been in the last couple years that I realized Charlotte’s Web might be one of the biggest influences in my writing life.

I fell in love with this book the first time I read it. I was maybe eight or nine, just around the age of the heroine Fern. But a couple years back, on the 60th anniversary of its publication, I decided to read it again.

What a revelation. It is, of course, maybe the most famous kid book ever. It won the Newbery and remains the bestselling children’s paperback even today. But what I didn’t realize is that it is a terrific story for adults. Like the Harry Potter books, it has a magic that transcends age and a theme that resonates deeper the older you become.

I pulled out my copy last week and read it yet again. Yes, it still holds up for me. But I also tried to look at it with different eyes and dissect how it works as a novel. It has lessons to teach any writer working in any genre.

First off, it teaches us to write from our inner selves, from the most shadowed places of our hearts. I think this is what the adage “write what you know” really means. It does not mean write about your narrow everyday world. It means write about what is essential to your unique soul.

E.B. White has said the story came from his childhood memory of being unable to save a piglet. But in his book The Story of Charlotte’s Web, Michael Sims explains that in 1949, White found an spider egg sac in his Maine barn and cut the sac out of the web with a razor blade. He put the sac in an empty candy box, punched some holes in it, and absent-mindedly put the box atop his bedroom bureau in New York. Weeks later, hundreds of spiderlings began to escape through the holes and spun webs on his hair brush, nail scissors and mirror. Thus was hatched White’s magical meditation that teaches us about life, death and the beauty of friendship.

But the book has many other things to teach us as writers.

Let’s start with the opening. I talk here often about picking the right moment to inject your reader into your conjured up world. And James writes often here about how you need to build your opening chapter around a “moment of disturbance.” Something has to happen. And it has to happen early enough in your plot to engage the reader’s interest. So how does Charlotte’s Web begin?

It’s breakfast time at the Arable family farm. Fern comes in to the table to see her father heading out to the barn with an ax. Mom tells her that one of the piglets is a runt and father is going out to do away with it.

Yikes. Gets my attention! Notice White didn’t start his story with Fern waking up in her little bedroom and thinking about the cute piglets that were born yesterday. He didn’t start it with a beautiful description of the Arable family farm. He went right for the dramatic heart. And what a great contrast he set up in our imagination: The warmth of a morning kitchen and a man leaving it with an ax on his way to a “murder.”

And is there a more chilling opening line in all of fiction: “Where’s father going with that ax?” Fern asked.

THE LESSON: Don’t waste time with pages of gorgeous description. Find the right moment to parachute the reader into your story. Build tension as quickly as you can.

Fern runs outside and we learn in a quick brushstroke that “the grass was wet and the earth smelled like springtime.” The crying Fern confronts her father that killing the piglet isn’t fair. To which dad says “you have to learn to control yourself.” Which is backstory, right? We now know Fern has a history of impetuousness. Dad relents and tells her she can bottle-feed the runt so she’ll learn how hard life can be.

THE LESSON: White sets up the protagonist’s challenge and has begun Fern’s character arc. And he starts plumbing the first level of the most important question an author must answer about motivation: What does the character want? Well, level one: Fern wants to save the pig.

We then meet her brother Avery, who wants to know why he can’t have a pig, too. Dad says “I only distribute pigs to early risers. Fern was up at daylight trying to rid the world of injustice.” (Level two: Fern wants the world to be just)

White then slows things down with a nice narrative about how Wilbur the pig thrived under Fern’s care. But then Dad says that Wilbur is old enough to be sold to the Zuckermans. Fern cries but Wilbur is banished to a manure pile.

THE LESSON: Your plot must have a series of setbacks for the heroine to deal with and overcome.

Chapter 3 opens with a long and lovely description of the Zuckerman barn. Because the plot is chugging along now, readers will be willing to slow down.

THE LESSON: Good pacing isn’t just a matter of full speed ahead. You have to know when to slow down and let the reader catch his breath. A good plot is a roller coaster with a series of tense climbs, terrifying plunges, and areas where you coast along – “whew!” – while you anticipate the next dip.

We then switch to Wilbur’s point of view as he meets the barnyard animals, each one indelibly drawn, especially the goose who helps Wilbur escape and Templeton the rat who steals his food. Fern hasn’t been to see him and Wilbur feels lonely and friendless.

THE LESSON: Don’t neglect secondary characters. Make them vivid and useful to the main character, be it a sidekick, foil, confidante – or a nefarious rat. Good secondary characters are prisms through which reader “see” the main character.

Speaking of secondary characters…has there ever been a finer one then Charlotte the spider? From her first lines – “Do you want friend, Wilbur? I’ve watched you all day and I like you” – we can’t help but love her. She’s smart (“Salutations! It’s just my fancy way of saying hello!”) and pretty and good at catching flies.

Wilbur is appalled by the fact she traps and eats bugs. He thinks she’s cruel. But in a matter-of-fact monologue, Charlotte explains that is what her kind has always done, that flies would take over the world if not for spiders, and besides, she fends for herself while he depends on the farmer to bring a slop pail.

THE LESSON: Never be content to create cardboard characters. Make every character as rich as you can — they are lightness and darkness — and find ways to make readers understand your characters’ complexities.

Next, the plot turns dark when the goose tells Wilbur he’s being fattened up to become Christmas ham dinner. Wilbur is distraught but Charlotte says, “Don’t worry, I’ll save you.”

THE LESSON: All good plots are a series of setbacks. Wilbur thickens and so does the plot.

In Chapter 9, in what feels like a digression with no relation to the plot, Charlotte explains to Wilbur and Fern why she has so many legs and how she makes a web.

THE LESSON: Readers like to learn things about how the world works, but you have to weave such narratives subtly into your plot or they are boring or worse, preachy. Don’t show off your research. Have it relate to your characters. White slips in this factoid: It took eight years to build the Queensborough Bridge but Charlotte says this only to comment that men “rush rush rush every minute…”

Then we come to the “The Miracle.” Charlotte conjures up a plan to save Wilbur by weaving the words SOME PIG into her web. The Zuckermans are gobsmacked and decide Wilbur is special. People flock to see the miracle pig.

THE LESSON: Give your characters setbacks to overcome, but a good plot also includes triumphs, which usually escalate as the climax nears.

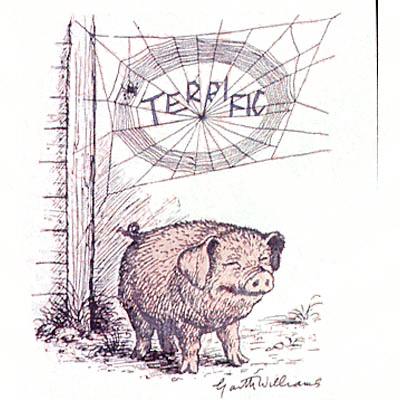

Charlotte worries that people are getting bored with SOME PIG so she gets Templeton the rat to go fetch some words from magazines that she can copy into the web. She weaves TERRIFIC and then RADIANT. The excited Zuckermans think of ways to exploit their pig.

THE LESSON: Always look for ways to up the ante, increase the stakes.

Chapter 14 is titled “The Crickets.” It’s a lovely descriptive dirge about the dying of summer. School would start soon. The goslings are growing up. The maple tree turns red with anxiety. “The crickets spread the rumor of sadness and change.”

THE LESSON: A little foreshadowing and mood is good but don’t be heavy-handed. Let it flow naturally from your setting. This is also White telling us what the theme of his story is – that life is about the inevitability of sadness and change.

The Zuckermans take Wilbur to the county fair for display. Charlotte, who needs to lay her eggs, reluctantly agrees to come along. At the fair, Wilbur is worried about a rival pig taking top prize and tells Charlotte to spin a special word for him. Charlotte confides that she’s not feeling well – “I feel like the end of a very long day” — but she promises to try. The cool of the evening comes and everyone is bedding down. White give us this wonderful dialogue between two old friends.

“What are you doing up there, Charlotte?”

“Oh, making something,” she said.

“Is it something for me? ” asked Wilbur.

“No,” said Charlotte. “It’s something for me, for a change.”

“Please tell me what it is,” begged Wilbur.

“I’ll tell you in the morning,” she said. “When the first light comes into the sky and the sparrows stir and the cows rattle their chains, when the rooster crows and the stars fade, when early cars whisper along the highway, you look up here and I’ll show you something. I will show you my masterpiece.”

THE LESSON: Yes, you should tug on the heartstrings. But whatever emotion you are going for must be well-earned. We have come to know and love these characters and as White moves us toward his climax, we have a soft dread in our hearts. Every emotion he has invested in this scene has come organically. Nothing feels tacked-on or artificial. Everything has pointed toward this logical end.

The fair opens and Wilbur, standing under Charlotte’s latest spun-word HUMBLE, wins a special prize. At night, left alone, Wilbur listens to fading Charlotte deliver her poignant speech about death and renewal:

“Your success in the ring this morning was, to a small degree, my success. Your future is assured. You will live, secure and safe, Wilbur. Nothing can harm you now. These autumn days will shorten and grow cold. The leaves will shake loose from the trees and fall. Christmas will come, then the snows of winter. You will live to enjoy the beauty of the frozen world…Winter will pass, the days will lengthen, the ice will melt in the pasture pond. The song sparrow will return and sing, the frogs will awake, the warm wind will blow again. All these sights and sounds and smells will be yours to enjoy, Wilbur, this lovely world, these precious days…”

“Why did you do all this for me? ” he asked. “I don’t deserve it. I’ve never done anything for you.”

“You have been my friend,” replied Charlotte. “That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you. After all, what’s a life, anyway? We’re born, we live a little while, we die. A spider’s life can’t help being something of a mess, with all this trapping and eating flies. By helping you, perhaps I was trying to lift up my life a trifle. Heaven knows anyone’s life can stand a little of that.”

THE LESSON: Don’t neglect your theme. It is the heart of your machine, purring beneath the grind of your plot. When you are asked, “What is your book about?” the answer is never about its plot. It is about its theme.

Then, of course, Charlotte dies. Here is how White ends this chapter:

“Good-bye!” she whispered. Then she summoned all her strength and waved one of her front legs at him. She never moved again. Next day, as the Ferris wheel was being taken apart and the race horses were being loaded into vans and the entertainers were packing up their belongings and driving away in their trailers, Charlotte died. The Fair Grounds were soon deserted. The sheds and buildings were empty and forlorn. The infield was littered with bottles and trash. Nobody, of the hundreds of people that had visited the Fair, knew that a grey spider had played the most important part of all. No one was with her when she died.

THE LESSON: Sometimes you must kill off a sympathetic character. If it serves your plot and it is not gratuitous, the reader will accept it. But it must have a feeling of inevitability so that when the readers comes to this point they are sad but acknowledge there was no other way.

Chapter 22 is titled “A Warm Wind.” Life at the farm resumes its cycle. The snows melt, the sparrow chicks hatch. The last remnants of Charlotte’s tattered web float away. Wilbur misses Charlotte but one morning, her egg sac – which he had carefully brought back to the farm in his mouth – erupts and her babies emerge. Wilbur is happy to meet the new spiders but one day Zuckerman opens the barn and a soft wind carries the babies away. Wilbur is crushed, thinking he has lost his new friends. But three of Charlotte’s daughter stay and begin weaving webs above him.

THE LESSON: Don’t neglect the denouement. A powerful story doesn’t end at the climax. There should be a tail to the tale wherein you wrap up some loose ends if needed, update readers on time passage and what has happens to some of the characters. In White’s story, of course, the denouement is also a coda of hope. Life goes on. Depending on the tone of your story, a happy ending might not be in your recipe. But a hint of redemption or hope is never a bad thing.

Which goes to the point of theme. In the final chapter, the narrative recounts the passage of months and years. Fern, growing up, doesn’t come to the barn much. But every year, Wilbur has new spider friends – the offspring of his good friend Charlotte. Here’s the last graph of the book.

Wilbur never forgot Charlotte. Although he loved her children and grandchildren dearly, none of the new spiders ever quite took her place in his heart. She was in a class by herself. It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.

THE LESSON: Bring it home. Your ending graphs are as important as your opening ones. A good story is circular in that it wraps back around itself, weaving a web of logic and emotion that captures your reader and leaves them with a feeling of satisfaction.